Summer is almost upon us, and there’s nothing like wasting summer’s delightful weather indoors with a good movie. But if it’s true that to everything there is a season, that must certainly apply to some directors as well. When it comes to summer, one director stands heads and shoulders above the rest for his affection for and insight into the season, the legendary Frenchman Éric Rohmer.

Rohmer (a pseudonym for Jean Marie Schérer) was an editor of an influential film magazine, and along with some of his colleagues at the Cahiers du Cinéma, a founding pillar of the “French New Wave” film movement.

And yet Rohmer was always an odd fit within the movement he helped kickstart. While his contemporaries were young upstarts, he was already something of an elder statesman, older by a decade and married with a family. Those fellow staff members were true leftists affiliated with the May ’68 movement and Rohmer subscribed to a monarchist publication. And while they were largely atheist, Rohmer was a practicing Catholic.

But Rohmer was never the type to lecture through his art. God is present in every Rohmer film yet he’s rarely explicit about it, and even when he is he’s never didactic. He understood film as a way of capturing the sacramentality of everyday life: God speaks in his films the same way he speaks in our lives, with a disinterest in actual words. God is felt but never seen, the same way you can sense a presence around a blind corner.

Rohmer brought this perspective to several different seasons, but always found himself returning to the summer — as if to rub it in our American faces, the French take five weeks of summer off. The season is central to the Gallic imagination, but Rohmer understood it better than any of his contemporaries precisely because of his Catholic approach. He knew it in its carnality and spirituality, and how its heights and doldrums were not so much contrasted as entwined. Rohmer grasped that summer isn’t a vacation from life, but rather a distillation of life itself.

Although his style has famously been compared to watching paint dry, it’s paint drying on a master’s canvas. Any female readers, or male readers with an aesthete girlfriend, will find much to appreciate with Rohmer. More so than any other French New Wave director, he had the accidental luck of anticipating Pinterest.

Rohmer was also a master at capturing the specific look of summer. He could tell the difference in how water and sweat make clothes cling to a body. He perceived the full spectrum of summer color, from the gaudy turquoise of a beach towel to the ritual of comparing skin tans. And his fashion sense has aged remarkably well, as a visit to any of the bougier beaches of LA County will demonstrate.

But summer is ironically something of an iceberg; there’s far more beneath the surface. Rohmer perceived that summer wasn’t just ballparks and barbecues, but also an opportunity for gnawing spiritual desolation. He understood that summers are frequently melancholic, the heightened pressure to enjoy yourself preventing the necessary relaxation to achieve it. His most fertile filmmaking is found in shortfall between expectation and reality.

A Rohmer vacation is often about taking a break from yourself rather than your job. Away from the bustle of Paris and surrounded by strangers at the beach, his characters find the anonymity to become their true selves or ponder when there isn’t a true self to discover.

Jerome from “Claire’s Knee” is an official diplomat yet conducts his love life like he’s conquering Poland. Delphine, the heroine of “The Green Ray,” bounds from beach town to beach town looking for a sense of relief, only to have her unhappiness already waiting for her at the train station. Inevitably, his characters find out in dawning horror that they are themselves wherever they are.

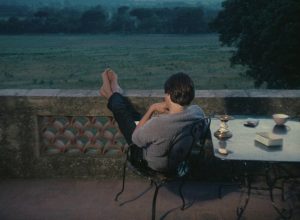

But Delphine, at least, is trying to find the solution. His other characters have already settled into themselves. They make no pretense of summer as a time of personal growth, unless you count melding into the surrounding vegetation. The “heroes” of “La Collectionneuse” don’t merely lounge, they sprawl across furniture like lizards sunning on a rock. The heat seemingly beats them into submission, and the only thing that rouses them out of indolence is attraction to the opposite sex.

While his scenes are fundamentally chaste, Rohmer is still French, so certain ribaldry is never far from the mind. Most of his films explore the conscious transience of the summer romance. The knowledge of a deliberate endpoint emboldens his characters for casual dalliances, in whatever form.

The two leads of “La Collectionneuse” fight over a single girl, and the dopey protagonist of “A Summer’s Tale” finds himself juggling three separate romances. Jerome from “Claire’s Knee” doesn’t even get that far, spending his languid efforts arranging a situation where he only caresses the titular knee.

All these encounters are inherently shallow because they treat summer as a fantasy, while Rohmer recognizes it as Eden. Away from the pettier distractions of society, existence becomes idealized, or perhaps actualized. His baser characters don’t recognize this, and by regarding vacation as an escape from life, their whole life becomes a vacation. They live for today, not in the Ecclesiastes sense but to avoid any grander commitment.

Rohmer doesn’t judge his creations, but he clearly admires those who take the opposite approach. Delphine from “The Green Ray” refuses to settle for an unsatisfying vacation, and hence an unsatisfying life. Her proactive stance pays off when she finally finds true love at the end, in the waning days of August. Felice in “A Tale of Winter” is similarly rewarded. After losing contact with her summer love, she refuses to commit to any other man, trusting that through some miracle they will find each other again.

Rohmer values faith more than any other virtue. These women smuggle the spirit of true summer back with them into cold reality, and as a reward he lets them keep the spoils past September.

Five “Rohmer Summer” recommendations: “La Collectionneuse,” “Claire’s Knee,” “Pauline at the Beach,” “The Green Ray,” “A Summer’s Tale.”