A team spread across three continents is using cutting-edge technology to shed new light on the figure of St. John Henry Newman.

The project, overseen by the National Institute for Newman Studies (NINS) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is aiming to offer crystal-clear digital reproductions of more than a million pages of documents relating to the 19th-century English theologian.

Newman was declared a saint Oct. 13, 2019, at the last canonization ceremony to take place at the Vatican before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, prompting renewed interest in his life and work.

Unlike other online Newman resources, the NINS Digital Collections is not limited to the saint’s writings. It also includes letters from thousands of people who corresponded with him.

Daniel T. Michaels, chief technology officer at the NINS, told CNA: “We’ve cataloged 1,840 different people so far who were writing to Newman or to whom Newman was writing. And we’re only up to 17,980 documents.”

“We’re up to box 75 of over 200. So we’re not even halfway through.”

For the past two years, Michaels has worked with colleagues in the United States, England, and India to create a free online archive of more than 250,000 manuscript images, over 4,000 published books and articles by Newman and his contemporaries, and library records, as well as photographs, maps, and musical scores.

He said: “We spent a solid year building the initial platform. We had scanned the images years ago, going back as far as the mid-2000s. A lot of Newman’s published works, such as ‘A Grammar of Assent’ or ‘The Idea of a University,’ were scanned and uploaded initially to archive.org. And so in some ways we’re reclaiming those documents, but they will remain available in both places.”

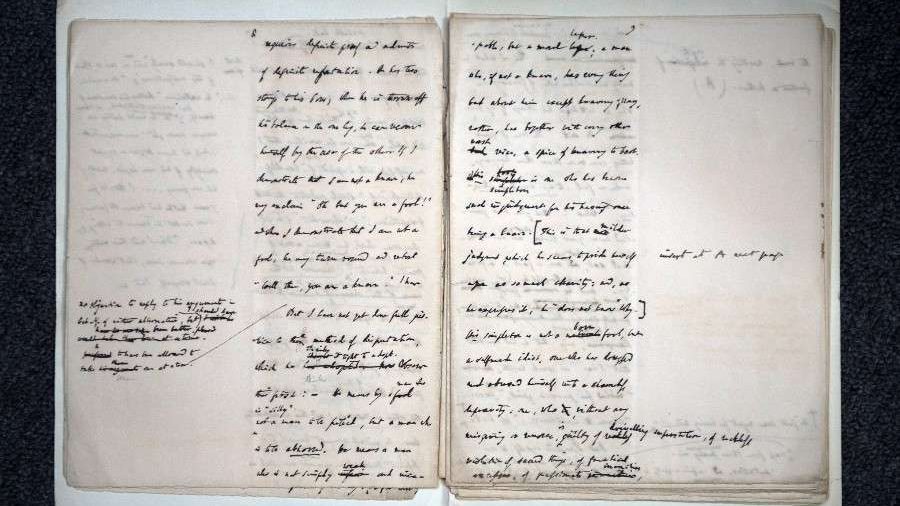

“Newman’s handwritten manuscripts, on the other hand, are available on NINS Digital Collections for the first time ever. Many of them have never been seen before.”

He continued: “We’ve had the images for quite some time -- both the published works and scanned manuscripts -- and we’re finally at the point where we can publish them on our own platform, which we’re quite pleased with.”

Michaels said that his team was standing “on the shoulders of giants” because the website of the NINS Digital Collections (pictured below) renders images “using lots of custom code alongside several open source technologies, including the International Image Interoperability Framework, or ‘triple-I-F,’ which is a programming interface that provides an unprecedented level of uniform and rich access to image-based resources.”

Michaels, who speaks passionately about the new technology, said that the best way to understand it is to think of a multi-tiered wedding cake. The bottom layer of the cake is the full high-resolution image. The next layer is half the resolution, and the next half of that, and so on, with the top layer as small as a fingertip.

He said: “We cut each layer into digital slices. A printed version of the actual image might be the size of an entire wall and it might contain hundreds of megabytes. But only a fraction of it fits on your computer, so we deliver slices -- bytes instead of megabytes -- as they are needed to improve speed.”

IIIF servers render “slices” of the document selected by the user from the most appropriate resolution layer of the “cake”, taking a piece from the high-resolution bottom layer when the user zooms in, or grabbing a slice from a lower resolution layer near the top of the “cake” when the user zooms out.

“So when you zoom in and out you’re actually only loading the data that pertains to whatever it is you’re looking at, sort of like Google Maps or Google Earth,” Michaels explained.

He emphasized that the process is “non-destructive” -- that is, the original images are preserved intact.

To illustrate the technology’s power, he summoned up a scan of the original handwritten score of Edward Elgar’s 1900 composition “The Dream of Gerontius,” inspired by Newman’s 1865 poem.

Next to it, he called up the published score. Finally, on the right of his screen, he placed a scan of the manuscript created by a technique known as backlighting, which reveals corrections that Elgar made to the score.

“You can see there’s paper glued over top,” he said, pointing with his cursor to where the composer had covered up a section of the music. “Scholars can see beneath things in a way that is not possible with the physical manuscript and naked eye alone: what did he change? What is he covering up, or how did the score change? It’s really incredible for musicology. We can do the same thing with the handwritten manuscripts as well.”

Asked if Newman’s spidery handwriting presented a challenge to his team, Michaels said: “We’re in the process of building another OCR [optical character recognition] engine using Transkribus, a German platform. It’s specifically made for 19th-century handwriting. We can train it to understand Newman’s handwriting. Then the accuracy is astounding.”

Michaels is especially proud of a feature on the website allowing scholars to search Newman’s borrowing record at Oriel College’s Senior Library in Oxford.

“We can compare what Newman was writing at a specific time with what he was reading. How often do you get a chance to do that?” he asked.

He recalled that a researcher was recently able to discover what works of St. Thomas Aquinas Newman was reading at a particular time. This helped the academic to see whether Aquinas influenced Newman’s views on a specific topic.

“It’s really valuable to Newman scholars, so that they can understand what was behind what he was writing. There’s not always a smoking gun, but it sure helps,” Michaels commented.

The Digital Collections do, of course, contain Newman’s own published works, including such monuments as his autobiographical “Apologia Pro Vita Sua” and his “Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine.”

Michaels contrasts the crisply rendered books on NINS Digital Collections with those on the popular Newman Reader website (also owned by NINS).

He said: “The Newman Reader is old school. It looks like it was done in 1995, even if it served a great need. It’s an HMTL version of Newman’s works and there are a lot of mistakes in it. NINS Digital Collections, on the other hand, shows the original published works. So instead of reading static HTML documents, you can read, search, and zoom inside the real thing.”

A search window on the NINS Digital Collections website lets scholars examine books for particular words or phrases.

“This was a significant thing for us to add -- and you don’t see this often with IIIF collections. That is, we can do full text searches across our entire inventory. It searches millions of words,” said Michaels.

“It’s way easier than the old Newman Reader. In fact, I cringe whenever anyone says: ‘Can you give me a link to the Newman Reader?’”

The coronavirus crisis has not paralyzed the team’s work. Indeed, Michaels said it had helped him to increase productivity because staff who normally worked in a physical library were able to join the virtual project.

“Our team is in California, Birmingham [England], and India. So we don’t ever not work remotely. If anything, this has given us more flexibility,” he noted.

“If you can imagine, between California, England and India, we’re basically running all the time. And so my schedule’s crazy. In the early morning hours, I might be meeting with the team in India before they go to bed, and Birmingham all the way up to noon. In the afternoon, I’ve got California. And in the evening, I’ve got California, and India as they arrive at work a day ahead of me.”

Michaels, who has a doctorate in medieval Franciscan theology and is the architect of a website containing the foundational works of the Franciscan tradition, said he had discovered a different dimension to Newman while working on the project.

“What was unique to me was seeing his pastoral side. The Newman that most people get is very heavy. He’s obviously very academic,” he said, pointing out that the saint served as a parish priest and that his letters were often concerned with practical matters such as building schools and caring for orphans.

While the team is still busy perfecting the platform, Michaels hopes that NINS might one day be able to share its pioneering model inexpensively with other institutions.

“It cost us a lot of money to do and fortunately we had very generous benefactors. But for a very low cost, we could make this possible for other people to share,” he said.

Asked why the Newman project was valuable, Michaels replied: “We’re basically preserving the past to serve the future. If we don’t understand where we’ve been, it’s going to be hard to understand who we are and where we should go without recreating more mistakes.”