A man gets lost in the woods. He tries to climb a mountain, but three beasts block his path. Fleeing, he meets the ghost of a poet who died 12 centuries earlier, and together they set off on a journey that brings him through hell, purgatory, and paradise.

Thus begins “The Divine Comedy,” the three-part epic poem that has enshrined Dante Alighieri as one of Western civilization’s greatest writers.

For centuries, scholars like Vincenzo Arnone have dedicated much of their life’s work to further understanding the literary, historical, and spiritual genius behind each of the poem’s 15,000 lines. To mark the “Year of Dante” in 2021, Arnone, a retired Catholic high school principal from Turin, Italy, is leading a YouTube lecture series titled “Walking with Dante” to accompany 21st-century readers of “The Divine Comedy.”

Ahead of the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death on September 14, 2021, Angelus spoke to Arnone, who credits Dante with helping him “re-understand” the meaning of his own life, about how the poet’s reflections on freedom, happiness, and true love can help guide readers through their own journey “out of the woods.”

How should we read Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” in 2021? As a “real” mystical experience or just a piece of fiction?

In a letter to his leading patron, Cangrande della Scala, Dante called his work “polysemous,” or “of many senses.” The first sense is that which comes from the letter, the “literal”; the second is that which is signified by the letter, the “allegorical.”

He adds: “The subject of the whole work, taken only from a literal standpoint, is simply the status of the soul after death. … If the work is taken allegorically, however, the subject is man, either gaining or losing merit through his freedom of will.”

He also explains the purpose of his poem: “To remove those living in this life from the state of misery and to lead them to the state of happiness.”

A mystical experience? We cannot rule it out, but this does not explain the meaning and the goal of Dante’s poem. The subject of Dante’s work is man, every human being lost in the woods of life. And we should understand Dante’s fictional journey as the endless adventure that is our own journey through life, marked by an attempt to fulfill that desire for happiness that defines us as human beings.

In order to write “The Divine Comedy,” Dante left several other literary projects unfinished. Why is that? Why did Dante feel such urgency to write “The Divine Comedy”?

In order to write “The Divine Comedy,” Dante abandoned a major literary project that he had dedicated a lot of work to, the “Convivio” (the “Banquet”).

Through the metaphor of the “banquet of knowledge” this work, a collection of poems with prose commentaries, was meant to supply people with a philosophical “food” of sorts, in an effort to guide its readers to true happiness and true fulfillment. Dante abandoned this project when he realized that philosophical knowledge is not sufficient.

At the age of 9, Dante fell in love with Beatrice, a woman he loved until her premature death. After Beatrice’s death, he sought consolation in rational knowledge, in philosophy, but soon he realized that knowledge is not able to provide an answer commensurate with the depth and vastness of his own desire for beauty and happiness, a desire which had been sparked by his encounter with Beatrice. When Dante fell in love with Beatrice he experienced a glimpse, a foretaste of infinite happiness.

The famous critic Charles Singleton described “The Divine Comedy” as a “return to Beatrice.” For Dante, the whole poem is an attempt to recover that moment, the encounter that sparked in him the intuition of the divine and gifted him with a completely new way of writing love poetry.

Certainly there are other factors that contributed to his decision to write a poem to which, in Dante’s words, “both earth and heaven contributed”: Dante’s political setbacks, the failure of his earthly aspirations, as well as the jubilee of the year 1300, the first jubilee in the Church’s history. This event was supposed to bring Christianity back to authentic faith, bringing about a renewal that the Holy Spirit had already set in motion through the preaching of St. Dominic and St. Francis.

Dante wrote in a time and place where society was Christian. That is not the case today, and many Christians feel that the answer to a world that has abandoned Christianity is for Christians to abandon the world. Would Dante agree?

True, medieval society was Christian, yet the Christian world of Dante’s time was full of tensions and contradictions. The Church was torn within itself and constantly at war with political powers. Yet, the Middle Ages knew the “art of coming back,” or, we should say, “the art of conversion.”

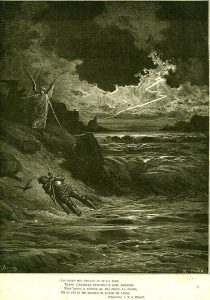

Perhaps the most intriguing figure in Dante’s “Comedy” in this respect is the character of Ulysses. Ulysses returns from the Trojan War after years of wandering. At the end of his life, he sets out on a journey in which he crosses the limits of the known world, the pillars of Hercules, in a vain attempt to achieve supreme knowledge, only to be overcome by a storm.

In a sense, Dante is a Christian Ulysses who succeeds where the classical character failed. First, he manages to go back home, the location that humanity was destined for in the first place: heaven, our true home. Then, like a new Ulysses, he crosses the uttermost limits of human experience — the true “pillars of Hercules,” death. He does so in order to recover life’s meaning, in order to rescue us from our constant wandering without hope of fulfilment.

But this is only possible if we are helped to take seriously our desire in its totality. Our desire is ultimately oriented toward the most desirable of all: the divine, the ultimate answer to human longing.

Dante describes this with an example: “We see that a little child’s greatest desire is an apple, and later, going further, he wishes to have a little bird … then a pretty garment … then a horse … then a woman … then some wealth … then even greater wealth.”

Our whole life is an incessant movement from desire to desire. What Dante wants us to realize is that our earthly desires, always increasing in size, are but a reflex of that longing for the infinite, a reflex we are marked with because we carry the imprint of God. And God attracts his creatures toward himself by letting himself be sought through the many desires that set us in motion in our everyday lives. The desire for earthly things is not a denial of the divine, but a concrete anticipation of that totalizing, inextinguishable desire.

The true masters among us, like Dante, are not those who teach us to see reality only as a source of temptation, but those who invite us not to stop at the countless small things that we fall in love with, to live our ambitions and desires as a springboard that launches us into the pursuit of increasingly greater desires, all the way to the most desirable: God.

Dante is commonly perceived as a merciless type, a moralistic writer who relished condemning his contemporaries and sentencing them to eternal punishment. Is that accurate?

People tend to focus more on “Inferno,” the first part of Dante’s poem, and thus they forget that mercy defeats the law many times in Dante’s poem. In “Purgatorio,” one sees time and again souls snatched from eternal punishment, souls who would be damned according to a rigid, legalistic application of the norms of Christian doctrine.

A good example is the story of Manfredi, who was excommunicated for his unbending political opposition to the papacy. He was killed in the battle of Benevento and buried in unconsecrated ground, as per the laws of the Church. Yet the mercy of God prevails. Manfredi recounts: “My sins and crimes were horrible to hear. God, though, unendingly is good. His arms enfold and grasp all those who turn to Him.”

But mercy cannot conflict with human freedom, which is the only thing that God refuses to overcome. Mercy is an initiative of God in response to the faintest movement of human freedom, the slightest opening of our hearts to him.

This is illustrated by another memorable character of “Purgatorio,” Buonconte of Montefeltro, a knight who fought alongside Dante in the battle of Campaldino. The spirit of Buonconte tells Dante how, pierced in his throat, he fled to die alone:

“I lost my sight,” he says, “and all my words ended in uttering Mary’s name. I fell — my flesh alone remaining there.”

A devil shows up immediately, ready to drag Buonconte to hell on account of his many sins. Yet an angel also arrives. God has heard the silent prayer uttered by the dying man, who crossed his hands and died with the name of Mary on his lips. The angel obviously succeeds in claiming Buonconte’s spirit. The devil’s words highlight the paradoxical logic of God’s mercy: “Why do you rob me, son of Heaven, of this [soul]? / You’d prize him from me for one little tear, / and carry off his everlasting part?”

Love is a crucial theme of “The Divine Comedy.” “Love that moves the sun and other stars” is the poem’s last line. How does Dante define love? And how does he understand the relationship between divine and human love?

Love for Dante is closely connected to desire. “No creation or creature was ever without love,” he writes; and when desire turns to that which someone likes “that turning is love.” But desire and love do not end when we seize the object of our desire, but they push us to go further, to discover who we are and who we are made for.

This appears clearly in one of “Inferno’s” most famous episodes, in which Dante hears the story of Paolo and Francesca, a pair of adulterous lovers (Francesca was married to Paolo’s brother, who murdered both upon discovering their affair) overwhelmed by a passion akin to what Dante, who was married to another woman, felt for Beatrice. Francesca and Paolo are condemned to hell not because they yielded to their desire for illicit love, but because they limited their own desire to the immediate object of their longing.

In other words, they blocked the trajectory of their desire, constraining their freedom to an object that cannot satisfy their thirst for happiness. They refused to look further toward the greater good and refused to follow in the direction into which their love, even if sinful, was pointing them: the infinite and the divine.

For Dante, what is essential is not the distinction between sacred and profane love, but whether people are prepared to travel, through love and desire, the full distance that separates them from the infinite.

What can Dante say to our profoundly divided world today? And to a Church that seems equally torn?

What Dante keeps saying, to the men and women of today as well as those of 700 years ago — and St. Francis’ canto in “Paradiso” proves it — is that the only way for us to be happy is to take our own “I” into our hands again.

This means taking our desire of happiness seriously, recognizing that we, like Dante, are lost in the woods of life. We need to beg for help and to follow those who are ahead of us along the path that, like Dante’s journey, reaches for the stars. This is the source of every change, of every rediscovery of our identity, and of the rediscovery of our particular vocations.