I was on an extended business trip last week, and the hotel I was staying in had several HBO channels. But just like my satellite system at home, I had all these options and very little to watch.

One HBO show that always intrigued me (but I’m too cheap to buy HBO at home) was the reboot of the sci-fi concept “Westworld.”

The original was written and directed by Michael Crichton, a man of many great ideas, like bringing dinosaurs back to life. If I had only thought of that, I’d be writing this piece from a chateau in the south of France instead of a home office in Van Nuys.

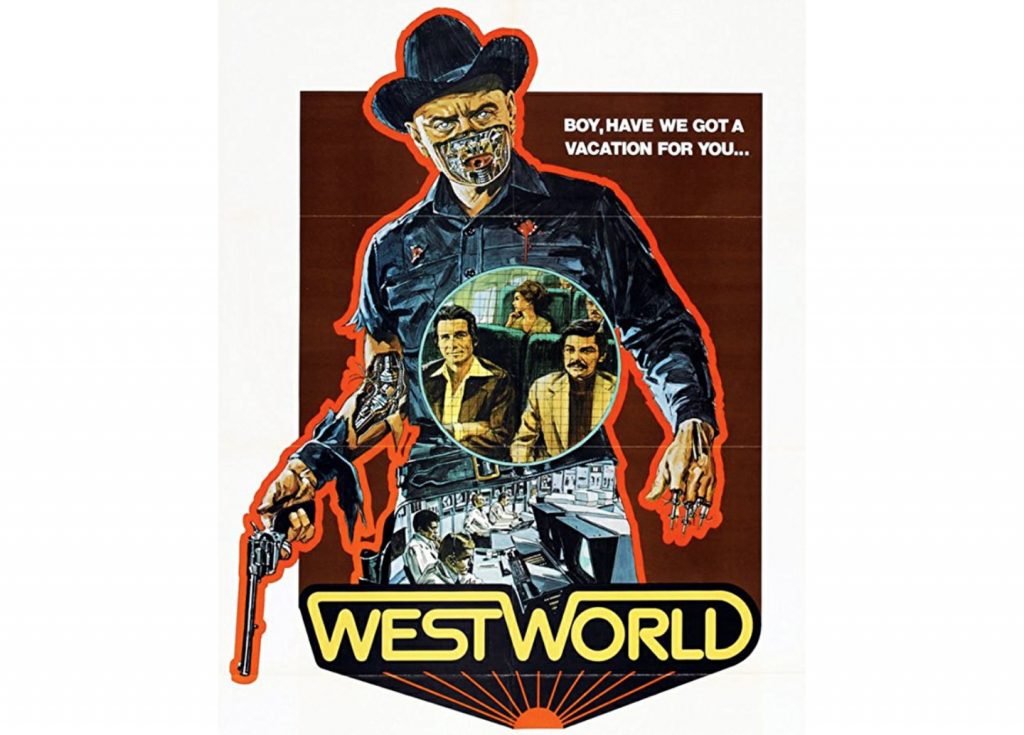

The original “Westworld” featured two friends leaving their humdrum modern-day existence behind to basically play cowboys in a town made up of guests and humanoid robots. In short order, something goes terribly wrong. The robots take on minds of their own, and our stars are soon running for their lives.

It was a brilliant idea made more effective by Yul Brynner’s weird performance as the robot gunfighter who relentlessly tracks our protagonists.

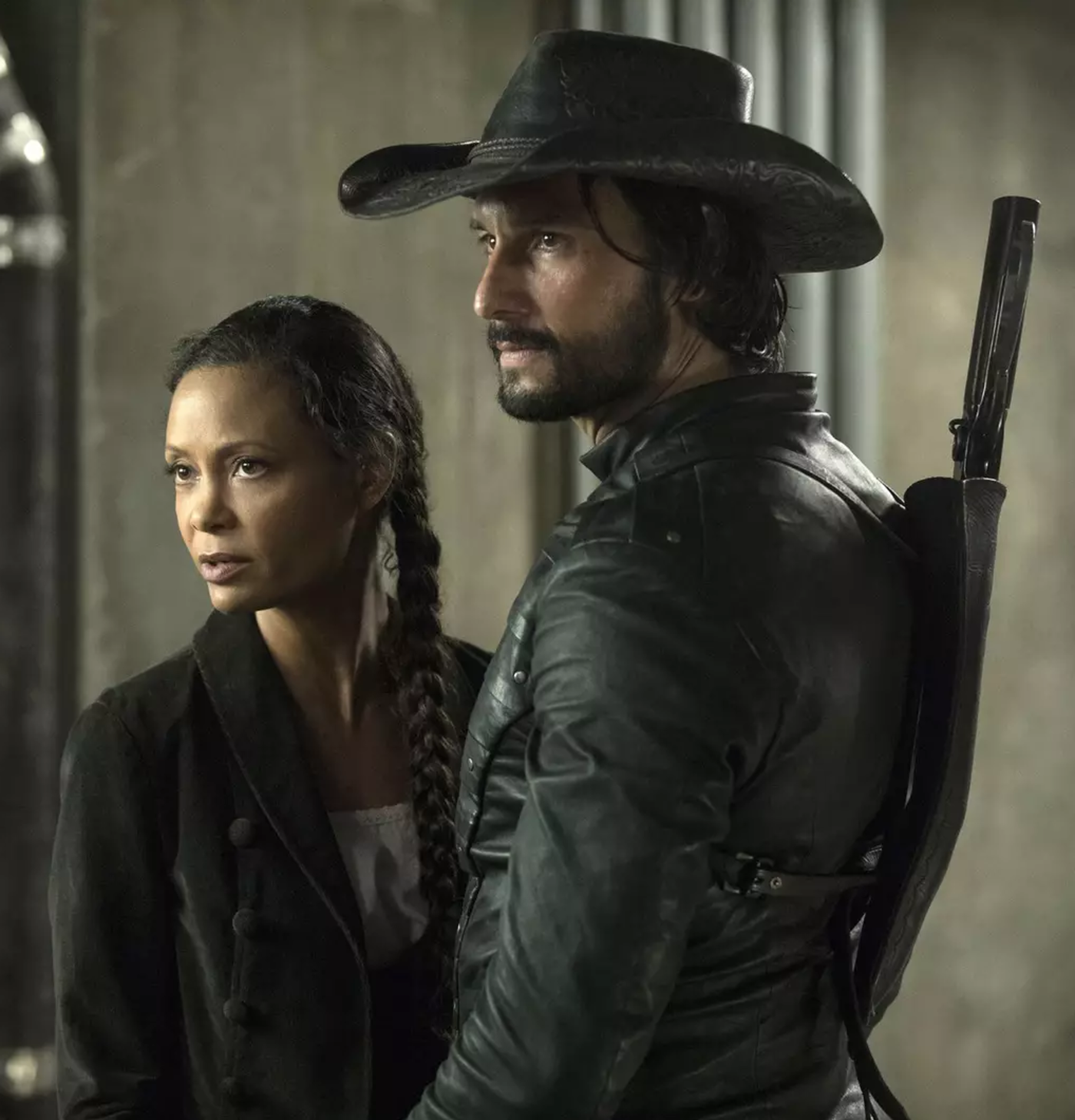

The term “protagonist” usually refers to the character or characters in a movie, TV show, book or play, and we’re supposed to relate to them, or identify with them, in some special way. In the “Westworld” reboot, manifested by HBO in a multipart series, it’s as hard to identify the show’s protagonists as it is to distinguish between the robots and the humans.

It’s stylistic to the max and has interesting performances, to be sure, but the episodes I watched while enjoying my free run of HBO left me cold.

Maybe that was the intent of the creators of this old concept made new. It certainly ties into the ennui of our times, where movies and television (especially free range and unencumbered venues as HBO) explore every facet of human behavior, no matter how deranged, or, in a not-so-distant past, disordered.

But the new “Westworld” and the old share the same basic premise, which has been scrutinized by artistic endeavor from the inception of the Pandora fable to Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” and up to the present multilayered plateaus that are entwined in HBO’s series.

The difference in the latest version, though, is that the robots and the humans are not just similar in physical ways, but very much similar in metaphysical ways as well.

It was interesting to see the new “Westworld,” as robots with advanced Artificial Intelligence contemplated the meaning of their lives.

Seeing human characters in the series doing the same thing, and coming to the same conclusion as their nonbiological counterparts, was disturbing. From my brief sampling of the series, both human and robot had cornered the meaninglessness market.

I’m not sure if the progenitor of the “Westworld” universe would share that opinion. I’m not sure that he wouldn’t either.

Michael Crichton was an interesting man, and although his writing wasn’t on the level of great American literature, he was a true “idea” man, who produced a large body of entertaining good reads. Many of them translated into spectacularly good movies and television shows.

He was also a contrarian — a man of science who kept his thoughts and beliefs of things outside the realm of science close to his vest.

Although I have no quantifiable evidence that Crichton believed in God, based on the books he wrote, I do know he was fascinated by humanity, even though — based on those same books — he found most human behavior unsavory. He did stipulate that it was better if humans weren’t shot by rampaging robot gunslingers or torn to bits in the jaws of a regenerated T. Rex.

The new “Westworld” does not make such a claim. Crichton criticized what he saw as science turning into a new religion by saying, “I am certain there is too much certainty in the world.”

He was all about established facts, and though his books are filled with human hubris, they also hold basic and readily identifiable facts of human decency in his protagonists.

As lushly produced and almost beautiful the reimagining of Crichton’s “Westworld” might be, the underlying nihilism is palatable and, at least for me, makes it hard to watch — a problem already solved, since I am no longer in a hotel room with free HBO, and I am too cheap to pay for it myself.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.