You can’t pick your favorite musician in the same way that you can’t pick your family. Something that personal can only be decided for you, often by those same relations you had no choice wading into a gene pool with. With distance my childhood becomes one contented blur, helped or not helped by my dad only driving white pickup trucks and seemingly only listening to one artist, country singer Toby Keith.

At the time, I chafed against the benevolent tyranny — and my seatbelt — in an attempt at the radio dial. But my little t-rex arms couldn’t reach that far, so I was forced to stretch my perspective instead.

Twenty years and some thousand miles away from my father’s truck, I discovered to my horror that I now loved Toby. The dial remains unbothered. Parenthood may be thankless, but never say it’s without its small victories.

Toby Keith passed away recently at 62, the second time in recent memory that cancer took one of my heroes before getting to ride off into the sunset, the other being Norm Macdonald. As befitting a man of his import and impact, Toby has been eulogized by slightly larger publications than this, such as The New York Times. They were even-handed and even kind in their tributes, but like many, mistook the legacy for the man.

One of the impressive, overlooked things about Toby Keith is that you could learn everything you needed to know about him from any album — all of which maintained a sonic uniformity from 1993 to 2023. But part of that consistency was a regular capacity to surprise, as if Toby knew who he was but was suspicious of others who assumed they did too.

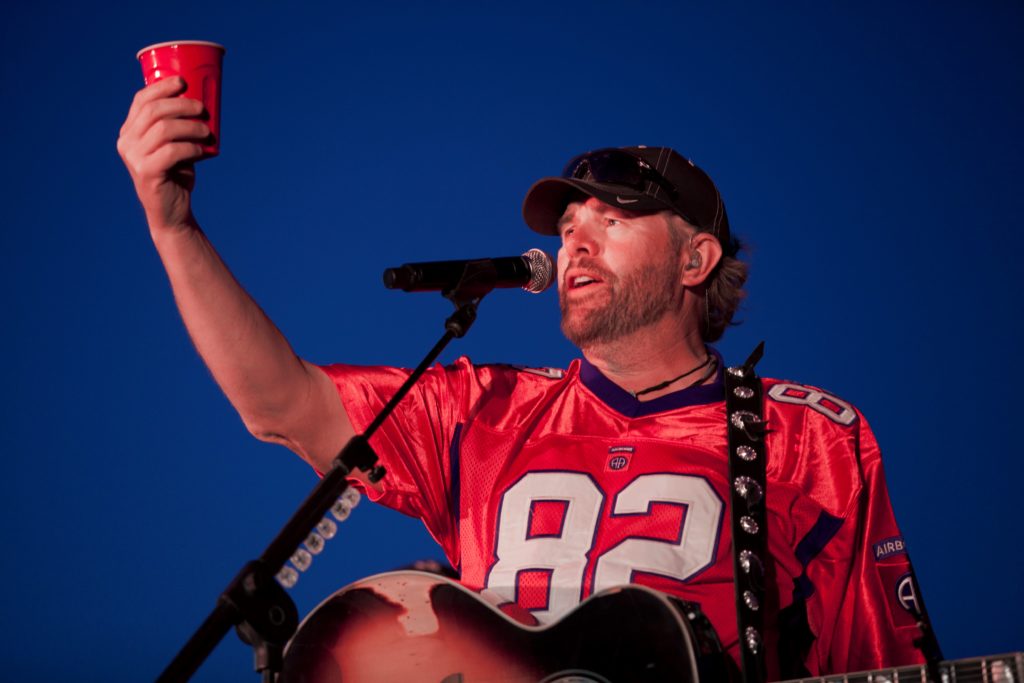

Perhaps the most ubiquitous image of Toby is him on a stage post 9/11, draped in a flag and threatening to place boots somewhere north of the foot. I doubt he would resent it, since that image helped make him wealthier than Jay-Z, Beyonce, or even Taylor Swift. Toby never apologized for “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue” for the simple reason that he wasn’t sorry. He never pretended to be pacifist and wanted revenge for those killed. Yet he was also against the Iraq War, which on closer inspection was more principle than paradox. He wanted justice, not a scapegoat.

Toby was a true American in all the pluralistic contradictions of the term. He supported the troops but not the war. He was as comfortable attending Trump’s inauguration as he was Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize ceremony. He is sometimes labeled as a symptom or even a cause of the partisan rift, but he had a more expansive notion of America than many downstream of him.

In his classic hit “I Love This Bar,” the bulk of his thesis is the diversity of its customers. His bar not only has the usual “blue-collar boys and rednecks” but also room for “yuppies” and “high-techs.” The bar is the watering hole, the microcosm of America. His invitation in the chorus to “come as you are” is a more genuine call to inclusion than anything an HR department could muster. Even after his acrimonious fight with the Dixie Chicks, they patched things up to the point of making plans to appear together in an Al Gore commercial to fight climate change. Never allow yourself to be past surprises.

But the truest example of Toby’s consistency and surprise comes from his music, as it very well should. Isn’t that what art is, revealing what you already suspect, but in ways you don’t expect? We all know and love his patriotic bangers, and any Fourth of July barbecue without them feels hollow and vaguely Leninist. But those were just the toppings of his catalog. The real meat was in his love songs. Toby was a passionate guy, be it for his country or his woman. Ask any Aztec: the human heart does not split so easily.

Country music is condescendingly praised for its simplicity, with pats on straw hats for managing to string together three chords and the truth. But when I praise Toby for his brevity, it comes from a man who has spent 700 words just to say he really liked him. The measure of a poet is not to use a thousand words but know which of the thousand you need. I say sincerely that Toby Keith was the last great poet of the past century.

Consider his divorce song “Who’s That Man.” The narrator ponders “if I pulled in would it cause a scene / they’re not really expecting me / those kids have been through hell / I hear they’ve adjusted well.” It’s an entire psychological profile, showing a man who loves his kids but somehow resents their ability to move on when he hasn’t. It’s hard enough fitting shoes into a suitcase, let alone a whole life in four lines.

Toby also had a great eye for detail. One of my favorite lyrics of any song is in his “Rodeo Moon,” which describes a married couple who travel the country competing in rodeos. “Now our windshield’s a painting that hangs in our room / it changes with each mile like the radio tune.” There is no finer synopsis of the American ethos. Here the country is both a gift and a calling, and home is more about what you carry within and beside you than where you stop. I’m sure in heaven Toby currently has F. Scott Fitzgerald in a firm headlock, taking his lunch money if currency still has use there.

My own favorite obituary of Toby belongs to my father, the man who started it all in a white pickup and wrote this on his Facebook: “One of music’s limitations is that it is a one-way street; an artist puts their thoughts into words and music, we absorb it and ruminate on it, but we don’t get the opportunity to tell them what it meant to us.”

This is the tragic result of music, that we never truly know the artist and they in turn never know us. But if there’s any consolation, it can help at least two fans understand each other just a bit better.