I come here not only to praise the late great television show “Breaking Bad,” but to bury it also…for now.

Due to the vagaries of the off-network television scheduling matrix, a show that broadcasted its final episode on Sept. 29, 2013 was still somehow eligible for Emmy consideration this August. As its newly-minted Emmy wins for Best Drama, Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor and Actress indicate, this remarkable show may be gone from the airways but still lingers in our communal consciousness.

By the luck of a television remote control click I stumbled upon the first episode of the first season of “Breaking Bad” and was hooked — probably not the best verb to use for a show about the murderous meth/amphetamine underworld. I have never been so transfixed by a TV show — and as someone who has watched entirely more television than a semi-upright hominid should, that’s saying a lot.

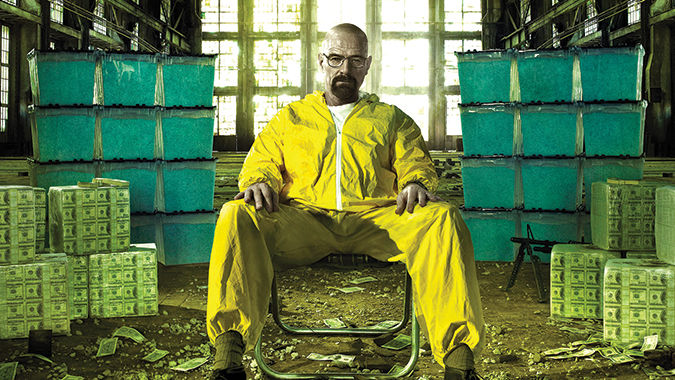

The object of my obsession, Walter White, so brilliantly portrayed by Emmy winner Bryan Cranston. There must be some built-in component to male DNA to mourn things that might have been and, if not careful, feed and water regrets.

Walter White is the poster child of that particular brand of narcissism, which may make him a problematic human being while at the same time, excellent fodder for interesting art.

Walter White is a walking, talking (mostly lying) example of middle aged despair and he was a character I couldn’t take my eyes off of during the entire run of this show, which, when I think about it, makes me a little worried about myself.

For the uninitiated: Walter White, mild-mannered high school chemistry teacher, morphs relentlessly into drug lord Heisenberg. This is not some kind of accidental transformation like Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll who spent that story arc trying to contain, control and eventually rid himself of his alter ego Hyde.

Not so with Walter White who embraces his inner Heisenberg and grows in self-confidence and power with every murder and successful subterfuge that conceals his true self.

As current as this kind of drama focus may be, Walter White owes a lot to classic tragic characters. He has a flaw (suppressed regret/anger), a life-altering encounter (cancer), and chooses a path of darkness at full gallop whereupon he inherits a whirlwind.

Lear’s hubris clouds his judgment and his rashness begins a chain reaction that decimates an entire royal household. Macbeth lusts for power and chooses murder. Ahab seethes with vengeance and pursues Moby Dick to death. The list could go on.

To me, the mark of a good show is that it takes the viewer to places that were not expected. At first, “Breaking Bad” seemed like a basic story of a good man choosing to do an evil act in order to serve the good of providing for his family after his impending death from cancer.

And as the body count began to escalate in the first season, the Church’s teaching on Double Effect seemed to be coming in loud and clear: The good effect cannot arise from the bad effect; otherwise, one would do evil to achieve good.

Halfway through the series it dawned on me that this was not the story of a good man who goes bad, but of a man with a lot of bad already in him who not only stops repressing it, but begins to nurture it. As someone once said, stress and strife doesn’t build character as much as reveal it.

Walter White is revealed as something less than admirable. The way he uses the second most important and interesting character, Jesse Pinkman, is nothing shy of pure evil.

I still revisit the show via my DVD collection and continue to get new takes on the same scenes. Though I focus on Walter White here, the show is rife with interesting characters all seamlessly cast with good actors.

If this seems obsessive I plead guilty, but as far as going back to the same material and extracting new insights, well, English professors have been making a good living doing that with William Shakespeare for centuries.

It’s OK. I haven’t completely gone off the edge of a cliff in Walter White’s Winnebago. Vince Gilligan, creator of “Breaking Bad,” probably has more in common with Mickey Spillane than with the Bard, but that is not an insult.

In many ways, “Breaking Bad” represents a uniquely American form of fiction. It was called Film Noir by full of themselves French film critics, but to the American masters who made them, they were just cheap quick investigations into the darker recesses of souls.

Those films may have been shot in black and white and “Breaking Bad” in color, but they all pay homage to the “gray” in the world and the bridge between who we really are and who we should strive to be.

Just like his literary forebears Lear, Macbeth and Ahab, Walter White’s incredibly bad decisions put him on the immutable path of his own destruction. The fact that the show’s finale attached a kind of “I did it my way” ode to modernism still cannot detract from this show being one of the most inspired, disturbing and downright addictive pieces of television to ever come around.

If you have not watched it and feel up to it, start binging on the complete set of DVDs at your leisure, but with a word of caution to…tread lightly.

Robert Brennan has been a professional writer for more than 30 years, including many years in the television industry. He has been a contributing writer for the National Catholic Register for many years and has also been published in Our Sunday Visitor and This Rock.