“Padre Pio,” starring Shia LaBeouf, is probably not the film you were expecting about the famous Capuchin priest from Pietrelcina. It’s directed, after all, by Abel Ferrara (of “Bad Lieutenant” fame), who was raised Catholic in the Bronx and today identifies as Buddhist.

But Ferrara has had a longtime fascination with religious themes, including Padre Pio — and audiences who are patient with the film to the end are rewarded with profound insights into his mission.

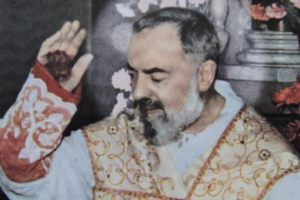

For Catholics, Pio is a much beloved saint known for his extraordinary gifts and miracles: the friar could read the minds of his penitents and bilocate (be present in two different locations at the same time). He had mystical encounters with Jesus and performed miraculous healings.

We see none of this in the film, set for limited release in theaters June 2. In Ferrara’s film, Pio is a young Capuchin who is yet to become famous. He leads a simple life of prayer and is barely known to the people of the southern Italian town of San Giovanni Rotondo.

The priest is played by LaBeouf of Disney Channel and “Transformers” fame, his first acting role after years away from acting, a time in which he reported feeling “totally lost.” LaBeouf has claimed — including in an interview with Bishop Robert Barron — that playing the role of Pio led him to embrace the Catholic faith. The seriousness of LaBeouf’s engagement with the great saint comes across in his acting: His Pio is a restless, tormented man, whose struggles feel authentic.

The film focuses on a single year in the saint’s life, 1920, and follows two separate threads. First, Pio’s interior journey, which leads him to an act of self-offering that will change the saint’s life forever. Then there are the political struggles in San Giovanni Rotondo, which lead up to a dramatic, though little known, incident. These two threads come together at the movie’s climax.

After World War I, Italy found itself with some meager territorial gain, more than 1 million dead, and a devastated economy which exacerbated social conflicts. The country’s Socialist Party made large strides among the population and met with the hostility of the landlords.

The situation escalated in 1920. The Socialists won the local election in San Giovanni Rotondo, but the Conservative Party backed by the landlords and the police refused to concede the victory. The police opened fire on the peasants who sought to enter the city hall to install their representative as mayor: Fourteen people were killed, including several women.

In “Padre Pio,” San Giovanni Rotondo is a microcosm of Italy and the events of 1920 are a harbinger of things to come. The increased violence and social conflict depicted in the movie will result in the rise of the fascist movement and Italy’s involvement in a second global armed conflict in just a few years.

As the devil says to Pio in a scene in the movie: “The last five years of misery [WWI] will be nothing to what is to come. A hundred million dead…”

“You’re looking at the end of the world,” director Ferrara told AP last year in an interview. He has dedicated the film to the victims of the 1920 massacre and the people of Ukraine, because “what I’m looking at is a rerun of World War II. Seventy-five million people died 70 years ago. That’s like, yesterday. It’s happening right in front of our eyes.”

A century of bloodshed in the making. How does Pio react to all this?

As the police shoot the peasants in the streets, Pio is celebrating the Eucharist. We hear the saint’s words, taken from one of his letters:

“This desire has been growing in my heart. It is now what I would call a strong passion. I have made this offering many times, beseeching Him to pour out on me all the punishments for all the sinners. This is my purpose.”

What “Padre Pio” does so effectively is propose again the scandal of the Incarnation. Jesus Christ appeared at a time of turmoil, with the fight between the Jewish population and their Roman oppressors. Jesus did not take sides. He did not undertake to free the people of Israel from the yoke of Rome. He did not seek to help the two sides find a compromise. Jesus’ response to the rising tide of evil was to let himself be destroyed by it — to let the sins of both Romans and Jews pin him on a cross.

In “Padre Pio,” we see the saint follow in Jesus’ footsteps. Pio remains indifferent to the political struggles. He does not take sides.

His response to the mounting violence, to the darkness that is about to cover the world again and push it into a catastrophe of historic proportions, is to ask God to let him suffer for the sinners, to turn all the evil against himself.

In the film’s last scene, we see blood pouring from the friar’s hands. Pio received the stigmata as a confirmation that his offer to God was accepted. Ferrara’s movie is true to Pio’s inspiration when it presents this offer — an innocent letting the evil of the world touch him in his flesh — as the antidote to the evil of the world.

But the movie stops short of attempting to unpack the full meaning of Padre Pio’s participation in the passion of Jesus. Jesus rose from the dead, and his resurrection proclaimed the outpouring of immense love and forgiveness as a response to human evil.

This is the kind of love Pio communicated to the multitudes that came for confession with him. Like his miraculous healings, the stigmata were external manifestations of his deep intimacy with God’s love: the same nature of Jesus, his love beyond death, is communicated to his faithful as it was communicated to the simple friar from Pietrelcina.