Can’t get enough of TV cooking star Gordon Ramsay’s trademark rages and rants? Their fictional equivalent is as close as your nearest multiplex, courtesy of the ego-driven culinary drama “Burnt” (Weinstein).

There’s a pleasant enough dessert awaiting audiences toward the end of this predictable conversion story. But its bad-boy protagonist’s tantrums make for an entree that many will find over-spiced — while some of the film’s thematic side dishes will not agree with palates attuned to traditional values.

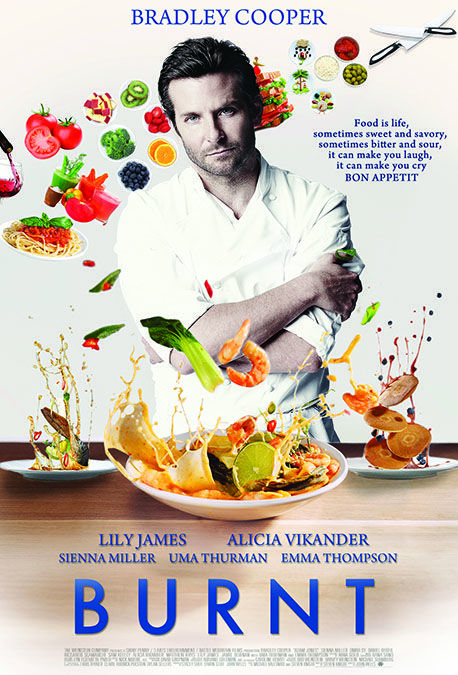

Although he well deserves a novelty apron declaring him the World’s Greatest Cook, perfection-hungry chef Adam Jones (Bradley Cooper) is a troubled soul. In fact, as “Burnt” opens, Adam’s alcohol and drug addictions have caused the Paris-trained toque’s once promising career to crash.

After completing a self-imposed penance — the shucking of one million oysters — clean, sober and temporarily celibate Adam is ready to return from exile via a well-choreographed comeback — the takeover of a faltering kitchen run by his old colleague, gifted maitre d’ Tony (Daniel Bruhl).

Unfortunately for those who have to earn their living at Adam’s side, and under his direction, his obsessive pursuit of gastronomical perfection is marked by obscenity-laden lectures berating all.

New to the scene of Adam’s wrath is his plucked-from-obscurity sous chef — and eventual true love — the fetching Helene (Sienna Miller).

Abundantly talented but entirely lacking in tranquility or any semblance of consideration for others, Adam will register with religiously grounded viewers as the embodiment of a familiar type of secular pathology. Absent any consciousness of the real deity, he elevates his craft into an idol before which all must kneel — and to the fuming demands of which all must be sacrificed.

Alongside the irritating curry of Adam’s impatience, there’s a subplot about Tony’s undisguised but unrequited love for the hunky hash-slinger. There’s a complex pathos in the discreet treatment of this subject, with Tony resigned to the impossibility of his desire and to the vaguely comic figure he cuts as a result of it. Ironically, his submission to the absurdity of his situation lends him a certain dignity, a pre-Stonewall sort of pride not to be found among clamoring protesters.

The film contains cohabitation, mature themes, including homosexuality, a same-sex kiss, about a half-dozen uses of profanity and constant rough and occasional crude language. (A-III, R).