There are some historical figures whose lives read like novels because their lives cross paths with so much history and the biographies of the famous.

It almost takes a “willing suspension of disbelief,” to borrow a phrase from Samuel Taylor Coleridge, to believe the details of their lives.

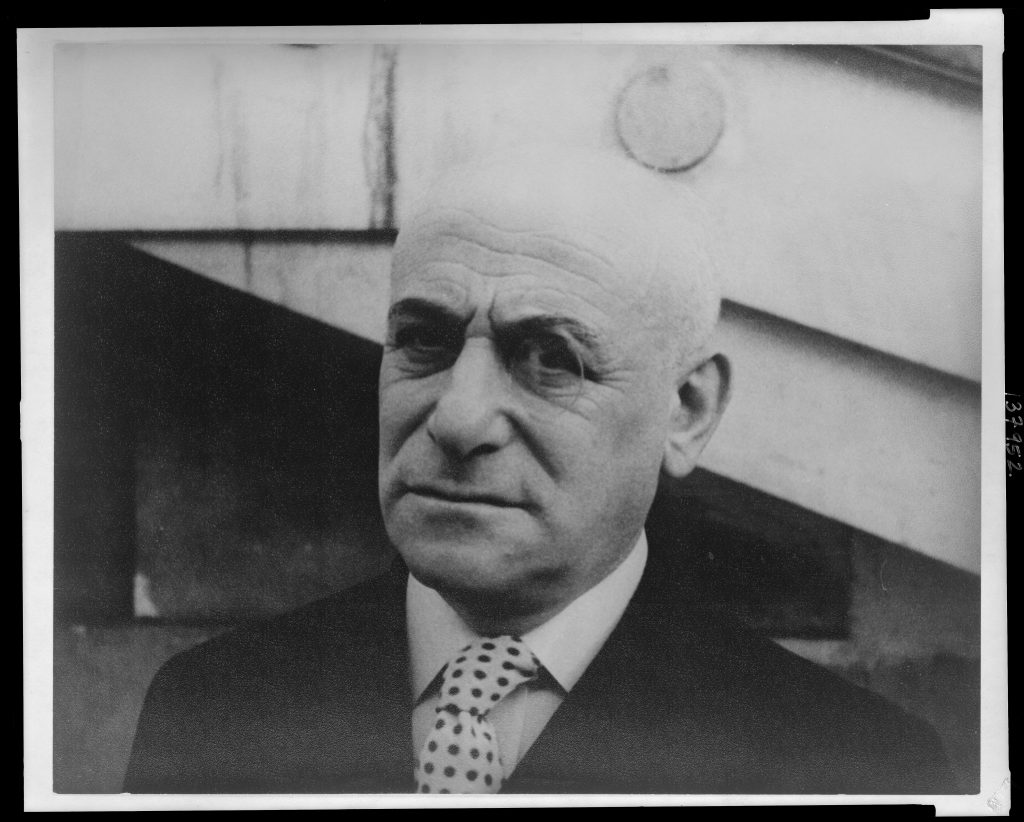

One such character is Max Jacob, a French poet who is the subject of a new biography by American writer and literary scholar Rosanna Warren of the University of Chicago.

A New York Times review of Warren’s book describes Jacob as “a marginal figure three times over — gay, ethnically Jewish, and hailing from the provinces.” But there’s plenty more in Jacob’s life that qualifies as extraordinary, from his devout Catholicism to his death at the hands of the Nazis while waiting to be sent to a concentration camp.

Born to an ethnically Jewish family that did not practice the Jewish religion, he converted to Catholicism as a young man in 1915. His onetime roommate, Pablo Picasso, was his godfather at baptism and gave him a copy of “The Imitation of Christ” as a christening gift.

In her book, Warren makes much of the intersection of the disparate groups and cultural movements in Jacob’s life and work. The Frenchman moved in avant-garde artistic circles typical of the first half of the 20th century, mingling with Cubist painters and writers like Guillaume Apollinaire, André Gide and Jean Cocteau. But he also was closely connected to Catholic philosopher (also a convert) Jacques Maritain.

His conversion was thanks to a mystical experience that involved seeing Christ’s image appear, “the Divine Body … on the wall of a shabby room,” and later on the screen of a cinema. His friends did not know what to make of his religion, and he covered much of the puzzling aspects of his personal faith with comedic exaggeration.

For instance, he was disappointed in seeing the streets of souvenir shops at Lourdes and joked that he also had seen the Blessed Virgin Mary, who looked very good, “for her age.” A French intellectual said of Jacob that he was a harlequin who never could get all the grease paint off his face.

Warren makes the case that his stature as a cultural figure is important. He was both a painter and a poet, and was awarded the Legion of Honor of France for his artistic achievements. Nevertheless, he never knew success or recognition outside of a small circle, and spent periods of his life as a lay associate at a monastery outside of Paris from 1921 to 1928 and then 1936 to 1944.

One of his remarks preserved in a book called “The Aesthetics of Max Jacob,” talks about a saint who is expelled from a monastery and asks God why that would be. He said God replied, “So that you could found your own monastery.” He never founded his own monastery, but Jacob certainly had some spiritual charisms, albeit mixed with contradictions. When people were skeptical of his religion because of his lifestyle, Jacob liked to quip that he believed in confession, which wipes away sins.

He wrote an essay called “The Defense of Tartufe,” in which he consciously accepted the charge of being like Moliere’s famous religious hypocrite. He was a “Tartufe,” spelled differently than the French playwright’s character, but a “sincere” one. He argued that belief does not make one immune from temptation and weakness. One contradicts one’s own principles and voila: a sincere hypocrite.

In his writings, mysticism jostles with the quotidian and fantasy. Watching pedestrians walking down the Rue Ravignan, he identifies the rag picker as Fyodor Dostoyevsky. He says that he progressed in life, “praying in God and believing in beauty.” Poverty, adverse conventional “opinion” and what he called the “stupidity of others” had shaped him and hardened him.

To this day, he continues to confuse the opinion makers.

The Washington Post review of Warren’s biography states that Jacob “regarded the Host as a kind of aspirin for every spiritual malaise” — which tells us something about the poet but more about the man writing the review (who pairs “aspirin” with “malaise”?).

Religious imagery is common in Jacob’s poems, especially those he wrote near the end of his life. In one poem he says he is absorbed in God, “the beautiful, the One who conceived this world, the Lord, the Gentleman-Genius,” and that his blood and Christ’s are mingled and enter a single heart.

Because of his sins, Jacob had a real fear of hell. A self-confessed sinner, the poet had a mystic sensibility.

“The river of my life has become a lake,” he writes in one poem, “What it reflects is nothing but Love. Love of God, Love in God.”

Jacob was arrested by the Gestapo at a private home after leaving the monastery. Like Edith Stein and her sister, conversion from Judaism was not enough to spare him from the Holocaust. It is said that he continued to joke even in Drancy, a camp where the Nazis held Jews before sending them east to the concentration camps. He died there of pneumonia on March 4, 1944, before he could be sent on to Auschwitz.

Some of his friends drew up a petition to have him released. Picasso, who owed much to him, refused to sign, saying, “Max is an angel and will fly over the walls.”

Jacob was a man of inconsistencies and contradictions: a poet who lived in poverty despite his famous friends, and who earned more selling his gouache watercolors in cafes than from his writings; a mystic who had a vision of Christ at the movies; a man unhappy with himself but intoxicated with God.

It is those contradictions that make the life of Jacob worth a look from Catholics. St. Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein) told her sister, “Let us go and die for our people,” on the way to Auschwitz. Max Jacob, a prisoner doomed to die, wrote a poem in which he said, “I thank you for having caused me to be born to the suffering Jewish race, for he alone is saved who suffers and who knows he suffers and offers his suffering to God.”

He is a sinner-saint for our complicated times. The concept of the divided self was not invented in our times, but has never been more generalized in culture. Jacob’s contradictions resonate with contemporary problems with identity.

“I don’t agree with myself,” he said, “I struggle against myself, against my heart, against everything.” What doesn’t match modern sensibility — his firm faith and his mystic grasp of “love of God and love in God” — is the most valuable thing he can teach us today.