The poet Mary Peelen has written about being influenced by the scientist Alan Lightman, particularly his book of essays The Accidental Universe. Lightman has noted that he thinks everyone “has had transcendent experiences, where you feel at least briefly that you are connected to something much larger than yourself.” As a scientist, he knows that “it would be very easy to be condescending toward the spiritual dimension of the world. I wanted to show that I do understand that—whether I’m a believer or an atheist, I have felt it myself.”

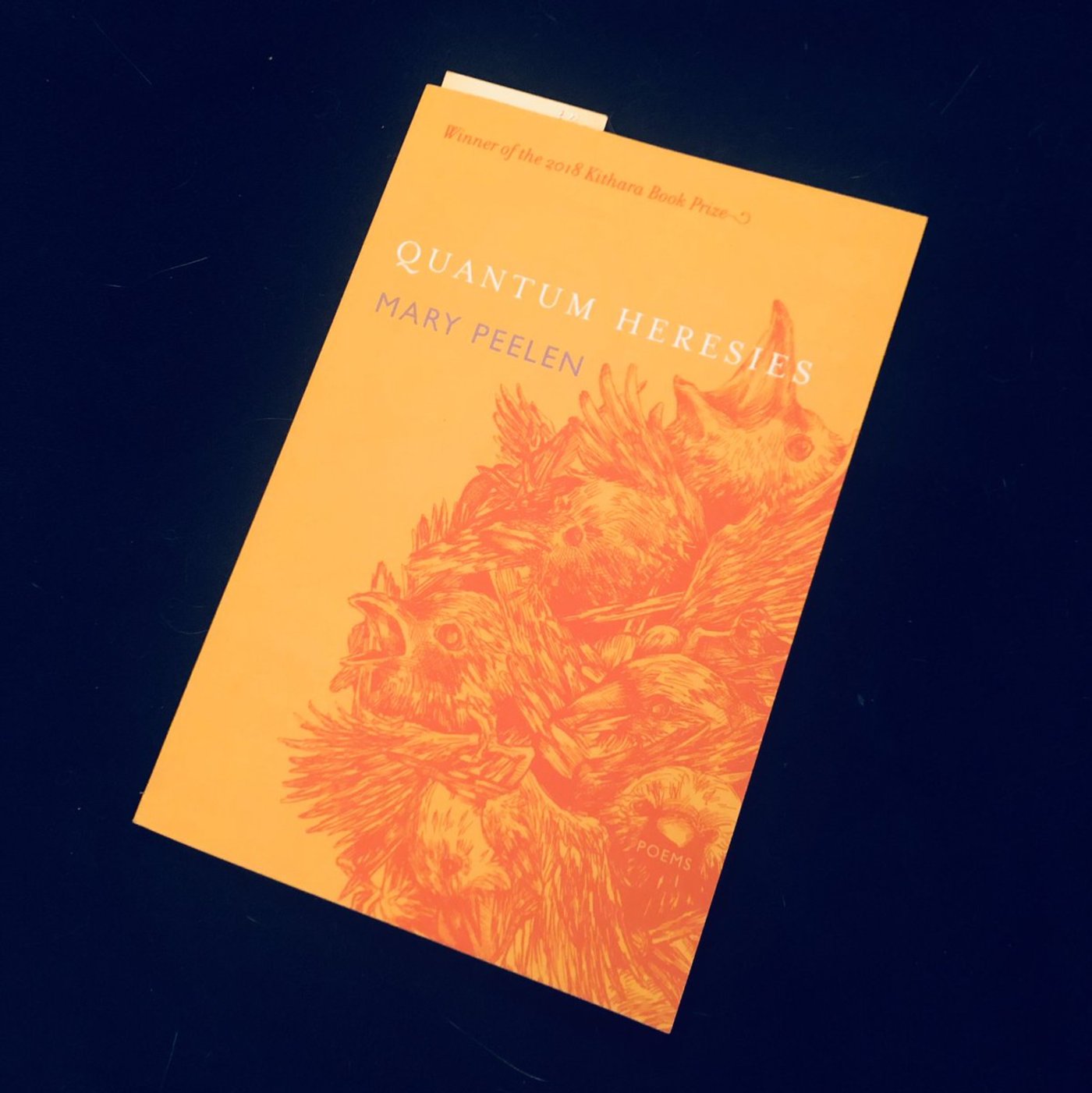

Quantum Heresies, Peelen’s debut collection, feels written in that vein of a poet-scientist, or scientist-poet. There is more wonder here than certainty; more faith than doubt. This is not to say that doubt doesn’t serve a particular purpose of giving the poet reason to look at, to conjecture about, and to document the world around her. Each poem in the collection is infused with a sense of mysticism, resulting in a book that effectively weds the scientific with the spiritual.

The book begins with a poem titled “x,” which introduces themes of mathematics, ambiguity, and God—particularly the misunderstanding that math focuses on merely quantifiable elements. The poem’s opening lines: “x obeys algebraic laws / but resists particularity. // It’s the placeholder / of uncertainty. // like the notion of / God.”

In “Supernova,” another poem early in the collection, we see that “Heaven performs a billion spectacular finales, / it’s up to us to conjure the rest.” A sense of cosmology can make us feel both inconsequential and special, a peculiar paradox that might often be also caused by poetry. “We’d all start with divinity and work backwards / if we could manage the math,” the narrator quips, lightly exposing the supposed divide between faith and science. Quantum Heresies bridges that gap in poems like “Chaos Theory.” “I learned in childhood,” the narrator recalls, “how destiny turns on tiny things, / cracks in the sidewalk, sticks and stones, // apparitions fulfilling the promise / of fundamental symmetry.” She begins to look for patterns in the world; indications, perhaps, of God. Her tactile world is filled with “gravestones and doxologies,” and of Grandma P, a reoccurring character in the collection. Her grandmother’s spirit is “exhorting me to trust in Jesus, / lorem ipsum of my soul’s erratic geometry.”

That geometry is sometimes understandable, but oftentimes seemingly arbitrary, as in “Prognosis”: “If cancer strikes you / as random or chaotic, // remember that like / every other algorithm, // it too has a unique function, / the elegance of its own logic.” For Peelen, the world—and our spiritual attempts to understand it—is elegant and graceful. Elegance doesn’t mean constant perfection and peace. Struggles abound in Quantum Heresies, as in “Aphasia,” when the narrator’s sister, in therapy, “recites her children’s names / like a profession of faith.” After the words “disappear / and it’s just me again, // benign, vaguely familiar.” The narrator pushes her sister’s chair to the window, where “Courtyard snow // melting in the afternoon sun / goes gray around the edges. // Rubber wheels on linoleum / make no sound at all.”

Gentle, contemplative lines abound in this book, as do poems like “Awake,” which move among subjects and moments. “For me,” the narrator writes, “there’s Calvinism to consider, / its inbred unworthiness, the voice of my mother,” and a ceremony “confounding as transfinite math / or the voice of Rilke’s angels in the firmament.” “Every infinity is terrifying,” she writes, and here terrifying takes on multiple meanings: a source of fear, wonder, and expanse.

Quantum Heresies brings to mind some lines from the Catholic convert Wallace Stevens: “We say God and the imagination are one… / How high that highest candle lights the dark.” In “Sunday Morning,” Peelen writes, she thinks of Stevens and “his quantum heresies, his dominion, / coffee and oranges, // birds defying gravity, / theory contained in a curved glass jar.” That juxtaposition between theory and glass, the metaphorical and physical, works nicely.

The collection’s final poem hearkens back to its first. In “Variable,” “The x could have been /anything at all, // the sound of wind chimes, / a gong, a choir, a cantor, // a mermaid, a schoolmarm, / cathedral bells.” It is none of those things, but rather, laughter of a man sitting across the street from the narrator, his “habits of hilarity / disciplined as a cleric.” The man’s “breath orders the world / into countable sets.” It’s a note of surprise, but also a suggestion from narrator to reader: open your ears and your eyes. Pay attention, because you never know when the world’s patterns will be revealed.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is a Contributing Editor for The Millions. He is writing a book on Catholic culture and literature in America for Fortress Press.