“Today it is axiomatic that we live in a global space fed by information from every point on the sphere at the same time,” noted the “Report on Project in Understanding New Media,” an ambitious, nearly 300-page analysis of changes in communication. “Electronic media,” the report continued, “demands the utmost spontaneity and resilience” on the part of its users.

Younger generations are more deft and comfortable with the new media than their parents and teachers. To borrow the language and spirit of the report, kids understand the “grammar” and “structure” of the new media. They are not merely literate; they are experts.

The comprehensive report offers a wealth of knowledge for educators, administrators, and parents. It is also more than 60 years old — and was the work of a devout Catholic named Marshall McLuhan.

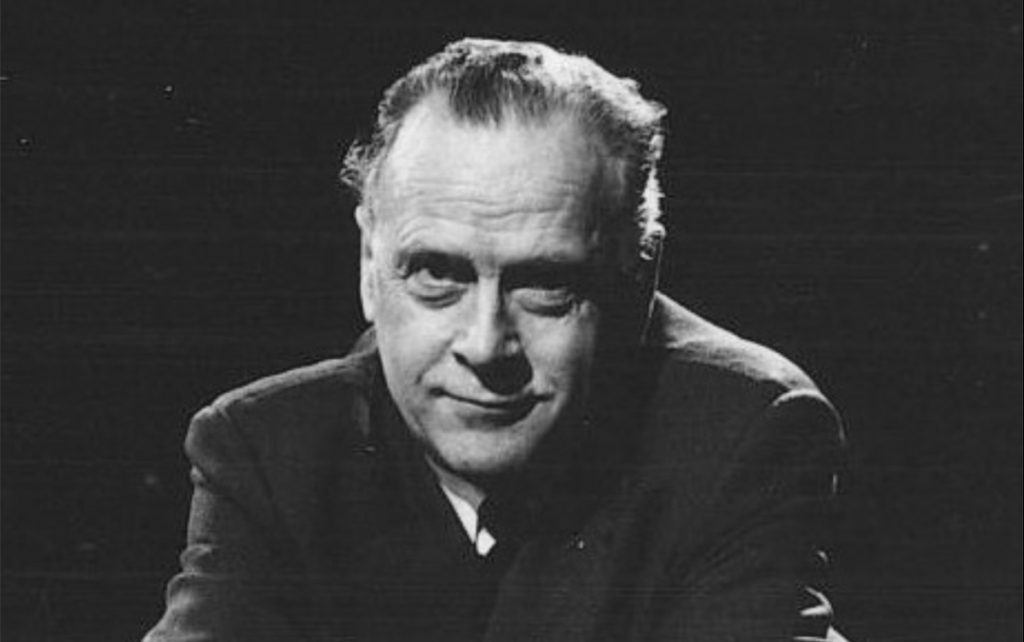

A quirky media theorist from the 1960s, now mostly known for his aphoristic statements (“the global village,” “the medium is the message”), McLuhan’s confident and sometimes cryptic arguments have come to fruition. As the consequences of the digital revolution become more painfully clear, he is finally getting the respect that he deserves, and yet many of his admirers still ignore his Catholicism. McLuhan’s faith was not mere ornamentation; it was the anchor and inspiration for his media theories.

Born in 1911 in Edmonton, Canada, and raised in what his son would later call “a loose sort of Protestantism,” McLuhan was culturally Christian, but not devout. That all changed while studying for his Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge, where he became enamored with the work of Catholic writers like G.K. Chesterton and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

To McLuhan, these writers showed how talented Christian artists could be profoundly intellectual. Rather than neutering their art, their Catholic identities compelled them to seek moral complexity. McLuhan was hooked. In 1937, he converted.

Inspired by his Catholic predecessors, McLuhan wrote in a 1946 letter, “I am conscious of a job to be done, one that I can do, and, truly, I do not wish to take any step in it that is not consonant with the will of God.”

McLuhan believed that his faith was a source of clarity and coherence; he believed that “Catholics can penetrate and dominate secular concerns — thanks to an emotional and spiritual economy denied to the confused secular mind.” McLuhan began a career of examining the various forms of media, from telephone to radio to television, focusing on how that media changed its users. His Catholic faith was an all-revealing microscope, enabling him to see the world clearly — and he endeavored to help others to do the same.

In 1959, the National Association of Educational Broadcasters commissioned McLuhan to research and write the “Understanding Media Project,” the goal of which was to “develop materials and the basis for instruction in the meanings and uses of the new media of TV and radio (in the context of other media) in American elementary and secondary schools.”

McLuhan thought the project was essential. He argued that “for centuries educators have lived under the monarchy of printing,” but with the newer media of “photography, movie, telegraph, telephone, radio, and television,” educators “now face students who, in terms of the information-flow of their experience, spend all their waking hours in classrooms without walls, as it were.” From McLuhan's perspective, if teachers could be converted to thinking with and through the new media, then the populist results could be significant.

McLuhan's project was not geared toward undergraduates or doctoral students; his aim was to modify the way that high school students were instructed. High school was the great populist education experiment, where the mass users and consumers of the media resided. It remains so today.

His final report was ambitious, and rather impractical — for its time. Now, though, McLuhan’s vision has become reality, and his radical reconsideration of education and media studies is exactly what teachers — including me — need to help kids.

For example, in his summary of the aims for his high school project, McLuhan observed that “obsession with ‘content’ seems infallibly to obscure the structural changes effected by media.” If we only teach students to get “better” at being online, without more conceptual awareness of how digital life creates an “environment” or experience that itself changes how we think, we risk falling into McLuhan's observed trap of content obsession. Although it might make us feel better to bark at kids to put away their phones, we need to understand what they seek to find in those digital spaces.

One of McLuhan’s especially Catholic observations was his skepticism of what he called the “global village.” The concept sounds nice enough — the idea that once united by instant communication, we can feel closer to people on the other side of the globe — but McLuhan realized that we should never misconstrue connection with community.

While it is true that we need to connect with others in order to form physical and digital communities, we must do so authentically. Long before social media was invented, McLuhan knew that a lack of privacy and contemplation could create antagonism.

Although McLuhan was skeptical of the increasingly connected world, he saw an opportunity for God’s presence to be discerned around the globe. He compelled all who would listen to think creatively and critically about what it means to connect with others from a distance. Even television could be seen as an opportunity: in McLuhan’s era, a family sitting around a television was a family together. With an open, Christ-focused mind, McLuhan was able to find the good in media.

McLuhan is fun to teach because he looks, acts, and talks like someone who shouldn’t have been “with it” in the 1960s, and appears even more dated to contemporary students. In McLuhan's own time, the younger generations most appreciated him. Older folks were the skeptical ones.

Most essentially, McLuhan compels us to remember that, in Christ, we are incarnationally united. That truth is digitally revealed when we recognize that being online is most dangerous when we are discarnate (and act as if we, and those whom we encounter online, are without bodies and souls). Although his original media report fell on skeptical ears, McLuhan is just the Catholic we all need — old and young — to understand how to live intentionally, and faithfully, online.