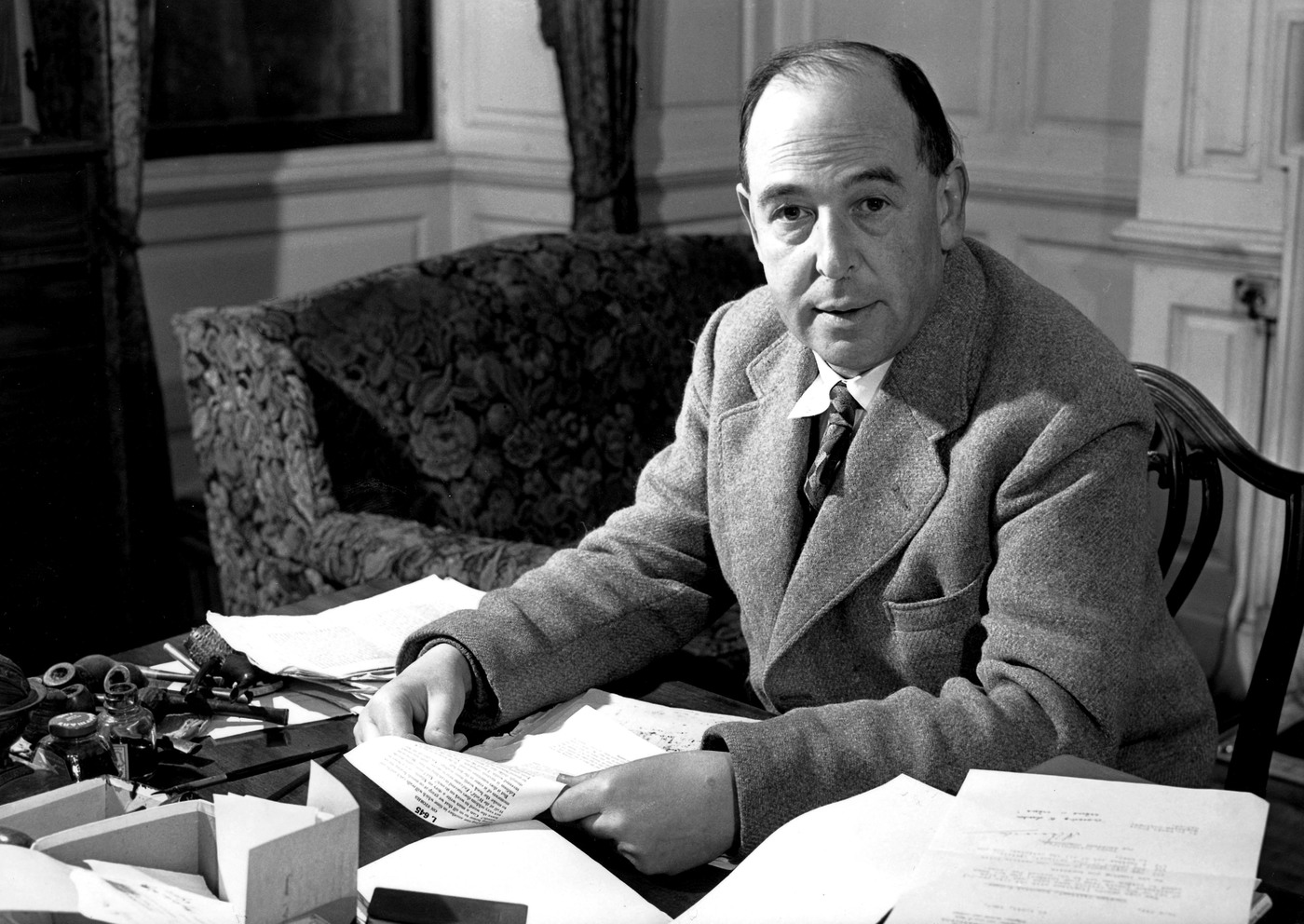

Among the most persuasive expositors of Christianity in the 20th century was C.S. Lewis. Among the most persuasive expositors of the Bible in the 21st century is Jordan Peterson. Lewis was a literature professor who explained Christianity to secular audiences, while Peterson is a professor of psychology who today seeks to explain the Bible, especially the stories of Genesis, in ways that resonate with secular audiences.

Both Peterson and Lewis appreciate the power of myth. But what is “myth” exactly? It’s an ambiguous term sometimes used to mean an entertaining but silly story naive people made up to explain what they did not understand. We could refer to this myth as narrative theoretical ignorance. Myth, in this sense of the term, is of its very nature opposed to facts, science, and truth.

But the term is also used to describe a narrative, poetic embodiment of deep insight for human living. We could call this myth as narrative practical wisdom. Myth in this sense goes beyond the empirically verifiable, but is not opposed to the facts found by science.

Myth as narrative practical wisdom embodies what is important to us, and what is important for us goes beyond what can be empirically verifiable. As Peterson puts it, “In the mythological world, what matters is what’s important. The world is made out of what matters, not of matter. It requires a very different orientation.”

Albert Einstein once made a similar point: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” So, insofar as we act, we all necessarily live in the mythological world, a word not reducible simply to the scientific method and what is empirically verifiable.

The world as investigated by science does not give us enough information to act in the world.

Science functions something like a metal detector. A metal detector is extremely useful for finding an engagement ring lost in the sand. But a metal detector is not what is needed if a man is deciding whether to give an engagement ring to his girlfriend or for the girlfriend in deciding whether to accept the ring.

Inasmuch as we must act in the world, we embody a view about what is valuable and what is not. “Everybody acts out a myth,” says Peterson, “but very few people know what their myth is. You should know what your myth is, because it might be a tragedy, and maybe you don’t want it to be. That’s really worth thinking about, because you have a pattern of behavior that characterizes you.”

Every culture has its myths because every culture embodies characteristic patterns of action. Inasmuch as there is a shared human nature, we would expect these stories to share commonalities.

“Because we’re all human and because we all share the same biological platform,” Peterson explains, “a platform that we share even with animals to a large degree, we tend to interpret the world in very similar ways. Those interpretations are often expressed in stories. The stories are descriptions about how human beings act, and our fundamental problem in the world is how to act.”

We can find similarities therefore between Christian stories and pagan stories, between narrative practical wisdom as articulated by the children of Abraham and narrative practical wisdom as articulated by the children of Homer.

Nor are these myths confined to the ancient world.

“They manifest themselves everywhere. They manifest themselves in movies and in books,” notes Peterson. “I mean, Harry Potter is a mythological story. It made Rowling richer than the Queen of England. You know, these stories have power.” We find such stories as “Sleeping Beauty,” “The Lion King,” and “Beauty and the Beast.”

Lewis and Peterson agree that the Christian narrative is something special, but for different reasons.

According to Peterson, “Christianity has done two things: it’s developed the most explicit doctrine of good versus evil, and it’s developed the most explicit and articulated doctrine of the logos.

“And so I would say, in many traditions, it’s implicit. It’s implicit in hero mythology, for example. I think what happens is that, if you aggregate enough hero myths and extract out the central theme, you end up with the logos. It’s the thing that’s common to all heroes.”

If you look at the story of the hero as told by pagan myths and in Hebrew writings, and extract the greatest characteristics of all these heroes, the greatest of all heroes is Christ. Lewis would certainly agree, but would have another explanation of the greatness of Christ.

Peterson declines to affirm or deny life after death, claiming that the “mythological landscape,” rather than “the objective world,” is the landscape of human experience.

Lewis, as a believing Christian, affirmed life after death in his writings. He saw Jesus Christ as overcoming the greatest threat to man: unlimited pain for an unlimited duration in an unending death, rather than the temporary pain or physical death that man experiences in the flesh.

Most importantly, Peterson and Lewis diverge on whether the narrative practical wisdom of the Christian narrative is also objectively, historically, and theoretically true.

In Lewis’ view, “The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the Dying God, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens — at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences.

“We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical Person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.”

Peterson seems, at least so far, to be still considering the question of whether the myth is also a fact.

When asked if he has faith, Peterson sometimes replies that he strives to live as if God exists. Father Richard John Neuhaus had a striking analysis of such a striving: “If you would believe,” he said, “act as though you believe, leaving it to God to know whether you believe, for such leaving it to God is faith.”