The 19th-century English poet William Wordsworth wrote a poem that began, “Milton! Thou shouldst be living at this hour; England has need of thee.” He wished the great poet had been alive to criticize the complacent corruption of his times.

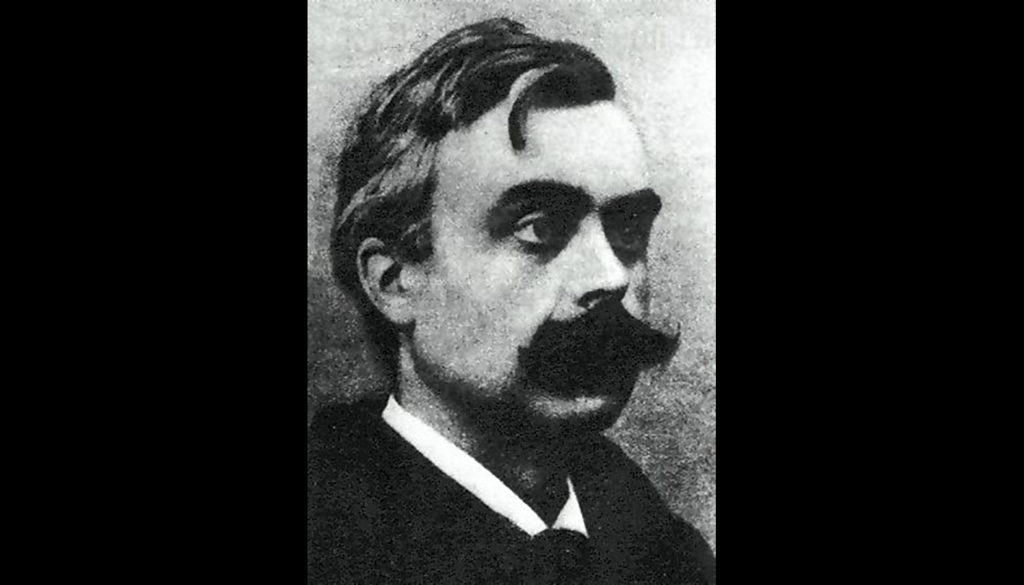

I think something like that about Léon Bloy, a French writer who died in 1917. I wish he were here to comment on the public figures today who do their best to keep their Catholic faith on the margin of their careers and personal comfort zones.

Although he is considered the father of the “Catholic” novel, Bloy is more famous for quotations extracted from them and from his brilliant and controversial journals published during his lifetime.

One journal was titled “Pilgrim of the Absolute,” which also became Bloy’s honorary title. Another, called “Bloy Before the Swine,” included a harsh depiction of his life in a Paris suburb. Those whom he’d turned to in his abject poverty and helped him probably agreed with another honorific, “The Ungrateful Beggar,” which was the title of another volume. His thought was that he could not compromise his writing or vocation, and expected others to support him in what publishers and the public refused to do.

It is a cliché that a prophet’s mission is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. But that seems to have been Bloy’s modus operandi.

France had responded with enthusiasm to the 1846 apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary to two young visionaries in the hamlet of La Salette. Its message of repentance was embraced by many but became controversial, even though the local bishop and the Vatican supported the claims.

But one of the visionaries, Melanie Calvat, felt that the message of Our Lady was not being correctly reflected and prophesied a coming disaster for the French Church. Her ideas resonated with Bloy, who became Calvat’s advocate and challenged the French hierarchy and the congregations who served as chaplains on the mountain where pilgrims visited the shrine built to mark the apparition. In his typical absolutist style, he said what had started with the charism of repentance associated with La Salette was now a matter of “hoteliers and merchants of soup,” because of the guesthouses run by the congregation on the “holy mountain.”

His identification with the cause of Calvat was a reflection of Bloy’s sympathy with those who were on the losing side of life. He also published defenses of Columbus and Napoleon, both of whom he judged maligned by historians.

Perhaps most quixotically, he believed, or wanted to believe, that the son of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, known to history as Louis XVII, had somehow survived imprisonment by Jacobin revolutionaries and lived in the Netherlands, missing all the action of the Napoleonic regime and the Bourbon Restoration. Bloy was fascinated with the idea that the powers of Europe knew the true heir to the French throne was alive and feared his possible restoration.

He was obsessed with the secret contrast of worldly appearance and the hidden grace of God. The world was not what it seemed; God was working behind the scenes in mysterious ways.

Bloy was a mystic about redemptive suffering, which he held to be the auxiliary of creation. Graham Greene, a writer in the tradition of Bloy, quoted him in the epigraph of his novel “The End of the Affair”: “Man has places in his heart which do not yet exist, and into them enters suffering in order that they may enter into existence.

He identified with the suffering of the poor and of sinners. Besides a conflictive and emotive nature, he was severely tempted by the flesh. Twice he entered into relationships with prostitutes, whom he tried to “redeem” until he fell into sin with them. One of them, Marie Roulet, eventually ended up in an insane asylum. Her supposed visions haunted him for the rest of his life. She eventually became the basis for a character in one of his novels.

His characters, like him, are caught in a struggle for existence and authenticity in a harsh and hostile world. If ever a real-life writer could have been a Dostoyevsky character, it would be Bloy. His contradictions could be shocking: When the Titanic sank, he wrote that the rich passengers deserved their fate while the poor in steerage were bound for heaven. He took very literally Jesus’ warning to the rich involving the camel passing through the needle’s eye, but perhaps had a more complicated hermeneutic interpreting the admonition “Love your enemies.”

Those who were loyal to Bloy, including his godchildren, Jacques and Raissa Maritain, leaders of a Catholic intellectual renaissance in France, overlooked his faults and saw him as a hero of unflinching honesty. Perhaps it was because his talent went unrecognized or because his uncompromising passion for the poor was so self-sacrificing, they esteemed his never-ending and unrewarded pursuit of God’s truth.

He was a poet in prose, the writer of memorable aphorisms and striking metaphors. He described his life as a country where it never ceased to rain. “Time,” he said, “was a dog who only bit poor people.”

Although praised by serious writers like Jorge Luis Borges, few read Bloy’s books today. He is still widely quoted by an unlikely range of thinkers, including unbelievers. Pope Francis cited him in his first homily after the conclave, saying, “When one does not profess Jesus Christ — I recall the phrase of Léon Bloy — ‘Whoever does not pray to God, prays to the devil.’ ”

This ungrateful beggar, the irascible pilgrim of the absolute in a world of the relative, the scourge of all hypocrites, “the hurler of curses” as he entitled a chapter in the “Pilgrim of the Absolute,” and the enemy of complacency died a pious old man on the outskirts of Paris.

He said, memorably, “The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.”

Bloy lived like the prophecy the angel said to Hagar of her son Ishmael, “He shall be a wild ass of a man, his hand against every man and every hand against him. (Genesis 16:12)” He lived at odds with his times, and with himself at times, but achieved an exceptional integrity. His was not an easy life. Yet I think perhaps he avoided what he called “the only great tragedy in life.” We could use some of his radicality now.