In 2019, poet Angela Alaimo O’Donnell traveled to the Holy Land. She spent her first night at the Mount of the Beatitudes. The next morning, she ran along the Sea of Galilee. In the days that followed, she made pilgrimages to holy sites, including Bethlehem, Jericho, the River Jordan, the Mount of Olives, and Calvary. She “followed in the footsteps of Jesus.”

Her fellow companions took photos. O’Donnell, instead, wrote poems.

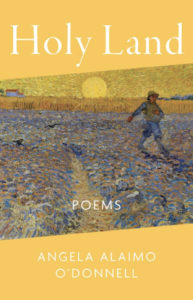

O’Donnell has collected these poems in the aptly titled “Holy Land” (Paraclete Press, $20), her 10th book of verse. One of the first poems in the book, “The Storm Chaser,” documents what she saw that first morning while running: “I see you in your boat, tall brown / man that you are, standing in the prow, / arms raised in supplication to the skies, / wind-whipped tunic blowing wild & high.”

The arresting image is followed by the fact that the man’s companions on the boat “have hit the deck and now lie prone / on the sodden wood, dumb as stone / and waiting for what surely is the end.”

While the wind tumults the sea, O’Donnell is transfixed by this man: “You alone are all might, pure motion / in the shape of a god, this small ocean / no match for your infinite love — for them, / for the sky, for the sea. And, yes, even for me.”

The man depicted in the poem was a real man — a fisherman who O’Donnell watched survive a sharp storm — and yet the man was also Jesus. One theme of “Holy Land” is that Jesus is among us, and not merely in spirit. Her poetry suggests that Jesus is among us in body.

Appropriately enough, as a poet, O’Donnell has been distinctly formed by Christ’s crucifixion. In her poem “The First Art,” she writes: “The rough wood splits and yaws / worn smooth in places / where hands, heads, buttocks, feet / of the crucified before Christ / rubbed and writhed and rested.” She has described the Catholic reaction to the crucifixion as a “complex mingling of fear and pity, guilt and gratitude, happiness and horror.” Those contrasting, powerful emotions created the need for poetry above all other art forms.

Thomas Merton, the Catholic poet and Trappist monk, once lamented that although Catholics have such a rich poetic tradition, many were ignorant of their literary forebears. As an example, he identified the mystical, entrancing St. John of the Cross as “one of the greatest Catholic poets,” but: “How many Catholics have even heard of him?”

Catholics should care about poetry, and I encourage them to encounter O’Donnell’s work. Her poetry is notable in both subject and style. She writes of the mystery of suffering and the worry of God’s absence. She does so paying close attention to the world, and her work manages to reveal joy while depicting life in an authentic manner. O’Donnell looks for Jesus in those she encounters, and she documents that search — and its revelations — in her poetry.

In “Holy Land,” her encounters with Jesus continue upon her return to America. “Easter Monday” is the prototypical O’Donnell poem: light-hearted, yet profound, as well as skilled and playful in technique. “Christ comes, a knock on the door when I least / expect him,” she writes. “Espresso in hand I pop open / the screen door that sticks in every kind / of weather.” He offers her peace, and joins her for breakfast; they eat “in the too-small nook, our four knees / touching beneath the table.”

The narrator and Christ “find / little to discuss.” The observation might first appear strange, but it forces us to consider: How would we receive Christ in our world? Are we ready to confront him in the flesh; to wrangle with the reality of his presence?

O’Donnell ends the poem: “His lined / face says he knows what we don’t say. / I ask him if this time he plans to stay.” Her concluding rhyme links the final two lines, and punctuates the poem as a prompt for the reader. O’Donnell’s poem is emotionally inviting rather than intellectual; it compels me to ponder my relationship with Christ in a visceral way.

She accomplishes similar power in “The Land of All Souls,” written for Nov. 2. O’Donnell’s most memorable work is both surprising and strange — a counter to the mundane appearance of life. “They are here with us at the breakfast table,” the poem begins,“sitting in our chairs, buttering their toast, / the knives heavy in their airy hands.” The departed are unable to eat; food, after all, is “for the living.” Instead, the souls “drift past us to the window seat. / They survey the days as if making plans.”

Ultimately, the souls “do what they always do, / stay here with us.” Those who have passed from this world “know they are loved, / seen and acknowledged by their flesh & blood. / They move through the day with us, side by side. / They almost believe they’re alive.”

The poem manages to be both melancholy and moving at the same time — a work that reveals the unique nature of Catholic poetry. The Catholic poet documents the travails of this world — suffering, confusion, fear — with an eye toward our saving grace. Poetry extends the liturgy beyond church walls. In writing and reading poetry, Catholics engage in a form of prayer and contemplation. “Holy Land” is a worthy companion on that pilgrimage.