A couple of Sundays ago, I drove over to Loyola Marymount for a reading by Jeff Dietrich, a founding member of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker. Members of the LACW run a soup kitchen in downtown’s Skid Row, offer shelter, food, and care to the marginalized and dying at their house in Boyle Heights, and regularly vigil for peace.

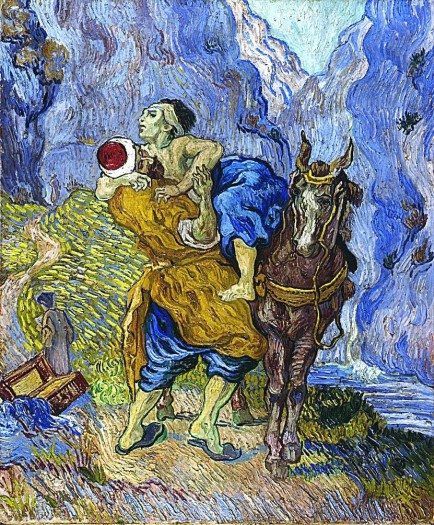

Published by Marymount Institute Press, The Good Samaritan is a handsome book — Jeff’s third — with a gray matte cover, ivory lettering and a raised illustration of Van Gogh’s iconic “The Good Samaritan” in sumptuous oranges and greens.

The essays are complemented by Madeline Wilson’s stunning black- and-white photographs and the superb woodcuts of Rufo Noriega. Printed on heavy photographic stock, the end result is just the kind of fine work we Catholics — especially we Catholics — should aim for: a book that demonstrates across-the-board excellence in craft, subject matter, layout, artwork, editing and publishing.

With respect to the craft: no surprise. Jeff is the longtime editor, designer and lead writer for The Catholic Agitator, the LACW’s bi-monthly newspaper.

As for the subject matter, “Comfort the Afflicted and Afflict the Comfortable” is the unofficial Catholic Worker mission statement, and this passage from “Who Is My Neighbor?” could stand as the credo for the book:

“In most of the Gospel stories, as with the story of the Good Samaritan, it is the oppressed and the marginated who can see: children, lepers, women, the blind and the lame, while the paragons of the social economy, the priests, Levites, Pharisees, Dives and the rich young man cannot.”

The essays date from 1976 (“On Trial”) to 2014 (“100 Years of Homeless Veterans”; “It’s a Wonderful Life”). In between are stories about some of Jeff’s heroes: Dorothy (“Don’t call me a saint!”) Day, LACW co-founder, along with Peter Maurin, of the Catholic Worker movement and Sister Megan Rice, the 82-year-old Plowshares activist who penetrated the Y-12 nuclear facility at Oak Ridge, Tenn., and was sentenced to 32 months in federal prison.

There’s a story about the suicide of Jeff’s schizophrenic brother Joe (“Families are weird”: Amen.). There are fresh takes on Gospel passages: the healing of Peter’s mother-in-law (Luke 4:31-37), Jacob’s ladder (Genesis 28:10-20). There are stories of arrests: for “malicious mischief” on the lawn of Pasadena City Hall, for cutting 750 yards of barbed-wire fencing at the Nevada Nuclear Test Site. There are stories of trials, of jail time.

Jeff weighs 140 pounds soaking wet. The top dogs in prison had 20-inch biceps. I’m reminded of Dorothy Day’s response to a reader who implied that the Berrigan Brothers might have been grandstanding in their anti-Vietnam war actions. “You cannot go to jail as a gesture,” she replied. “It is real suffering.”

Neither is rising in a drafty, unheated house, to make soup for the poor, every morning for 43 years, a gesture. Neither is changing the diapers of the dying. Neither is weighing the conundrum of the homeless man who comes to the soup kitchen before hours and asks to use the bathroom. As Jeff well knows, “Once a homeless person occupies your restroom, even a court order has no power to disrupt the urgency of his sanitary needs” — laundry, personal grooming, and the taking of makeshift showers.

Reading these essays, you see Skid Row, you hear Skid Row, you smell Skid Row. You remember that love is not a theory. Love is a face, love is a name: Mama B, Lequan and Clarence; Georgina and her German shepherd Sheba; Wheelchair Bob, an aggressive panhandler Jeff suspects may be faking his injuries — but of course feeds anyway.

You also remember that to sentimentalize “the poor” is to do them, us, and the nature of reality a gross injustice. Perhaps my favorite story was “The Miracle of Birth in a Skid Row Manger.”

It’s 1986 and in a freshly-scrubbed little room above the soup kitchen — the same room where a man named Freddy had lived and just died of renal failure caused by years of hard drinking — a woman named Rosa lies on a cot preparing to have a baby.

As Rosa labors, a midwife assists. A few community members sit vigil. “Outside on the corner below the street lamp,” Jeff writes, “the hookers kept their nightly vigil as well, displaying their wares and waving to passing traffic. Across the street, in a small park, Shorty and his buddy, Simon, sat warming themselves around a fire made of trash and old newspapers as they passed a ‘short dog’ of Santa Fe port to ward off the evening chill, trying to save a few drops for Rosa’s baby when they got the good news.”

There it all is in one splendid paragraph: the pageant of life, the light and the dark, the Eastern star perpetually rising over more poverty, more paradox, more suffering — and always, more joy. Because even the drunks — maybe especially the drunks — know to raise a toast to a newborn baby. Now that’s Christmas.

May the Eastern star continue to shine over the L.A. Catholic Worker, and over Jeff Dietrich’s stellar, important book.