For some, the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has been a time marked by confusion, loneliness, and suffering; for others, one marked by solidarity, generosity, and persevering love.

What explains the difference? How much depends on how much the pandemic has affected us in human terms like money or health? And how much depends on the perspective with which one approaches it?

Alongside those questions, the current crisis has given rise to questions about the role of faith — how can we make sense of tragedy and suffering on such a large scale, especially when it enters our personal lives? Is the assurance promised by religious belief enough for us in the current pandemic?

While not written with the coronavirus pandemic in mind, a new memoir by an emergency room doctor happens to offer a timely exploration of many of the question marks provoked by today’s global crisis.

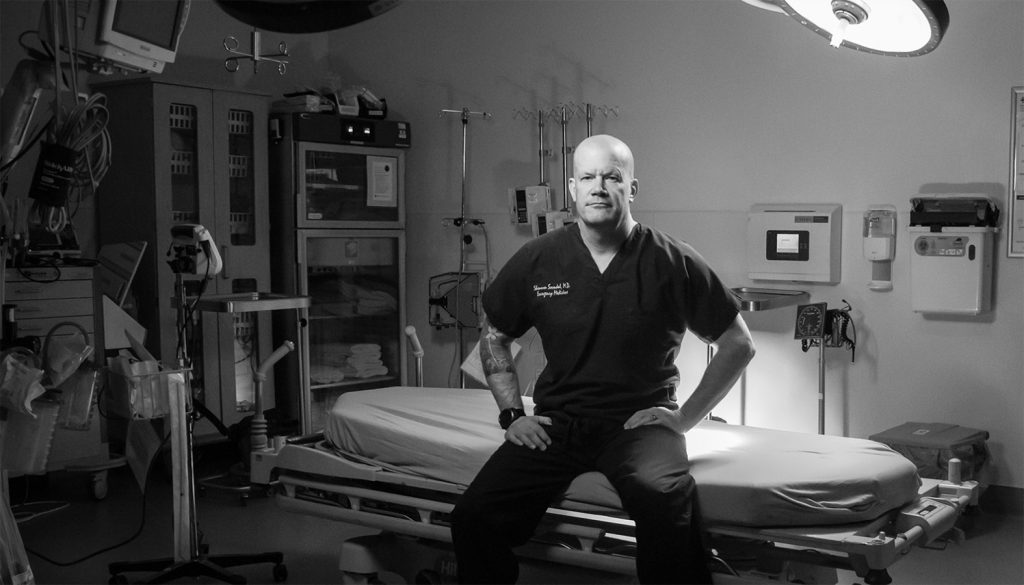

“Fragile” (Gyrfalcon Press, $16.95) by Shannon Sovndal is the autobiography of an Air Force cadet turned ER doctor. It is also a heart-wrenching account of a person in search of the assurance that faith brings but has not yet found it.

Raised in the Lutheran Church, Sovndal attended Catholic school and married a devout Christian. He spends most of the 236 pages recounting how his faith experiences — together with his life as an emergency medicine physician — shape his own questions about pain, loss, and purpose. And those questions don’t always get definitive answers.

Sovndal devotes the first few chapters of the story of his career, faith, and search for meaning in the face of suffering to memories of tending to an unconscious 3-year-old boy as his anxious mother looks on.

“She put her clenched fist over her mouth, trying to grab the air as it staccatoed its way out,” he writes of the mother. “Her body shook more vehemently. The pressure behind her eyes seemed too much.”

Sovndal describes his encounter with this woman as “gazing into a black hole.” Looking at her in the hospital room pulls him into a vortex of emotion that overwhelms her world in that moment. It’s an intimate connection, but also a risky one.

Sovndal’s challenge is to gaze into the black hole without getting sucked into it entirely, a balancing act involving human sympathy, professional composure in order to do his job, having to offer consolation, and maintaining his sanity all at the same time.

Sound familiar? All of us have felt pain, loss, fear at some point, and for many, the situation with the current pandemic has intensified those feelings. How do we empathize with one another’s pain without becoming overwhelmed by it?

For a Christian, the answer is Christ’s redemptive sacrifice: the certainty that the cross leads to the victory of the Resurrection and transforms all suffering into an opportunity to love and find eternal happiness. It’s been a common theme during the pandemic, especially since it has coincided with the Lenten and Easter seasons.

Sovndal’s tale is a deeply human one of a man trying to make sense of suffering and death without that assurance of faith. To his credit, the author is perfectly honest on this point. He admits that he has not found a satisfactory response to the question of suffering. Nevertheless, he maintains hope in the fundamental goodness of life. Why? Simply put, he recognizes the beauty of love.

“I really, really love my kids,” writes Sovndal. “ ‘I’m pretty into my wife’ is an understatement. I love big complicated things like black holes and time. But I also love simple things. Like a sunrise. Like a smile.”

Sovndal knows that relishing these things also involves a risk: being vulnerable. And in this wounded world, being vulnerable means that you might get hurt.

That risk is a daunting one, and it often compels us to play it safe, to avoid risk in order to escape pain. But that fear is paralyzing. “I feared death,” Sovndal writes. “But in doing so, I was truly afraid to live. The living risked loss. I was afraid to try.”

Sovndal comes to the conclusion that trying to avoid pain is not only futile, but it also distracts from the joys of life. What’s more, when we accept suffering as part of life, we can see it within the context of the beautiful painting of our existence; the shadowy corners make the brilliant focal points stand out.

“The key here is that I need the backdrop to enjoy all the things I really treasure,” he writes. “How do I know how to feel true love for my wife if I’ve never felt the sting of loss?”

With this, Sovndal reaches human conclusions to supernatural questions. His observations offer consolation, and they lead him to basic truths about love and purpose. He recognizes that while suffering is mysterious, there is meaning, also mysterious, that makes life beautiful nonetheless.

That Sovndal has not found a satisfactory response to the dilemma of suffering may disappoint some readers, his struggle still holds value and insight.

For those who have had faith transmitted to them from childhood, it is encouraging to see how a searching soul’s hunger for truth can bear some fruit. For us, the risk of becoming lukewarm or halfhearted in our convictions until they are no longer convictions at all is a real one during times of suffering and confusion. That’s why for Christian readers, “Fragile” should serve as a vivid reminder that God wants us to pursue him always, no matter where we are in our journey.

“Fragile” is a testament to that pursuit. Amid all kinds of tragedy, Sovndal finds that the meaning for which humans long indeed exists, even when they cannot fully explain it. His story is an example of hope against all odds and truth within the most baffling of circumstances. And even without having all the answers, Sovndal’s search for hope is one that can speak to believers and skeptics alike.

“Fragile” will be available for purchase beginning May 12.