What do you get when you bring 1,000 high school senior boys to their state capital for a week to build their own government? The answer: Boys State.

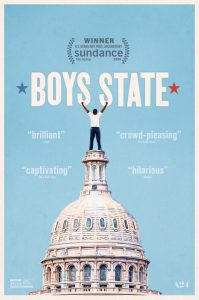

In a new documentary from Apple and A24, directors Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss place a magnifying glass over the Texas iteration of this educational program that has drawn thousands of young men since its founding in 1935, including future politicians and pundits such as Dick Cheney, Rush Limbaugh, and Cory Booker.

The film, which won the U.S. Grand Jury Prize for documentaries at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, highlights a handful of boys in the crowd of Texas teens as they work to build party platforms, deliver speeches, and elect leaders, all in the span of one week. Along the way, it offers a fascinating (and often entertaining) glimpse into how adolescent men do politics: from disorderly voting sessions to proposed bills for alien invasion defense systems or changing word pronunciations.

But when it comes to serious policy debates and competition for leadership, things turn ugly.

While “Boys State” has moments that cut through the “us versus them” mentality of politics, it only ends up perpetuating it.

As the documentary unfolds, four boys emerge as the central characters: Ben, an outspoken Reagan fan; Steven, a son of Mexican immigrants; René, a master of rhetoric originally from Chicago; and Rob, a fun-loving crowd pleaser bent on winning. René and Steven both identify themselves as liberals, while Ben and Rob espouse conservative viewpoints.

At first glance, this seems like a well-balanced setup: two protagonists from each end of the political spectrum. But before long, it becomes clear which side is the film’s favored one.

On one side there is René and Steven, underdogs who seem to be the only Boys State participants willing to reach across the aisle and prioritize values rather than victory at all costs. On the other is Ben and Rob, who are perfectly willing to lie and manipulate their way to victory.

By pitting these two sets of aspiring leaders — and only these two — against each other, the film presents an image of a morally pure left against a morally tarnished right.

René and Steven enter Boys State very much in the minority, both racially and politically. From the beginning, the film highlights their eagerness to listen to their peers, learn from others who think differently, and lead with integrity, all universally laudable qualities for any politician.

Their efforts win them some recognition: René is elected the Nationalist Party’s state chair, and Steven becomes the party’s candidate for Boys State governor, the program’s highest office.

Without doubt, both are appealing characters, and at first, Ben, who becomes state chair of the Federalist Party, seems so as well. Having lost both of his legs at age 3, Ben talks about how he understands struggle and wants to overcome labels to build American unity. But when he sets his mind to winning elections, we hear him talk about how to “spin” opponents’ past actions to cast them in an unfavorable light.

He encourages his fellow party members to promote derogatory social media campaigns against the Nationalists and seizes every moment to paint them as “corrupt” and “morally bankrupt.”

Rob, the other prominent conservative candidate, hardly gives a prettier picture of the right. In fact, we soon learn that he’s not really conservative at all. After repeatedly championing adoption over abortion in his speeches, he admits off-stage to the camera that he’s actually pro-choice but lies about his stance in order to win over the crowd.

Unfortunately, this is the most the film does to highlight conservative opinions and arguments. It spends some time highlighting Eddy, the Federalist gubernatorial candidate, but very little. And this marks a serious blow: Eddy comes off as congenial, sharp, and respectful, but all we really know about him is that he reminds a lot of people of Ben Shapiro. Ultimately, his role is overshadowed by Ben and, strangely, by Rob, who is only a primary candidate.

Such an editing decision not only gives the film a lopsided structure (we hardly know Steven’s chief opponent) but also robs it of a potential opportunity to offer a more nuanced portrayal of the conservative team.

Eddy’s back seat is not the only missed opportunity. While the boys occasionally mention the benefits of talking with others who have different opinions, the film only incorporates brief excerpts of such conversations, which quickly fall to the wayside. As a result, the partisan narrative predominates.

While this documentary may very well capture its protagonists’ true characters, their placement within its constructed narrative does the political landscape a disservice. It paints the right and left with broad brushstrokes, which makes for a dull image compared to what could have been a representation of each side’s strengths and weaknesses.

The key problem with “Boys State” is not that it treats conservatives unfairly. Indeed, for any Christian there are causes for alarm that span the full length of our country’s political spectrum nowadays, including the right.

What’s worrisome, however, is that by cherry-picking its protagonists, “Boys State” unfairly projects the divided politics of the Trump era onto the next generation of American leaders, most of whom are still trying to figure out what they believe in and what values they are willing to stand for.

The result of such selective portrayals, particularly when involving people of a young age, is the impression that there is more that divides than can unite us.

And, in times like these, we can probably all agree that division is the last thing our society needs.

“Boys State” is scheduled for limited theatrical release July 31 and release on Apple TV+ Aug. 14.