On an early Saturday afternoon in December 2019, Tomas and Juanita Bonilla were sitting at a table outside the cafeteria of Dolores Mission School in Boyle Heights to talk about a group that no one wants to be a part of.

Started in 2014, “Healing Hearts Restoring Hope” (HHRH) is for individuals whose lives have been forever changed by the homicide of a loved one, but who have focused on forgiving and healing.

For the Bonillas, that change came on Halloween 2010. Still angry about their recent breakup, the ex-boyfriend of their 19-year-old daughter, Zurisaday, drove his vehicle into the Bonilla’s home.

The car smashed through the bedroom where the family was, killing Zurisaday and 18-day-old baby Naomi. For the parents of four children, getting past such an unspeakable tragedy came down to the choice to forgive.

“I didn’t have time to think about him,” Tomas said of the man who murdered his daughter and granddaughter. “I was thinking about my wife, our other children. I talked to my wife, and she said she did not feel anything for him.”

The couple, who spoke to Angelus News while the group held its annual Christmas party, recalled feeling concern not only for their family but for that of the perpetrator, too.

“We focused on restoring and healing our other children first, and to make sure that our children were going to be OK,” recalled Juanita. “And we also knew the other family, who had recently lost their grandfather as well. So the pain that we were feeling, the other family must have felt as well. We understood that and focused on healing. We didn’t have time for hate.”

It was HHRH that helped the couple for what came next.

“When we chose to forgive, we were harshly judged by people who didn’t understand how we could forgive him,” said Juanita. “Coming to this group, we were not judged, which we appreciated. We felt that we could be who we were.”

Consuelo Valdez, HHRH executive director, who translated for the couple during the interview, called the Bonillas “walking examples of what it is to be compassionate.”

“They’re just a forgiving family — the way they have forgiven, the way they carry themselves and wanted to reconnect with the offender’s family,” she said. “It’s just God in their lives.”

Families who forgive

Since starting in her current role a year ago, Valdez has talked to many forgiving families like the Bonillas.

“I am amazed at all the families that I meet like them,” she said. “But I know it’s their faith, too. A lot of it is the faith that they have that carries them and supports them, and the fact that there’s a group that exists that understands.

“Every time I go to a group meeting, people say, ‘I feel safe here. I can say what I need to say. I can say what my feelings are. Because if I say it out there, people tell me I shouldn’t feel this way: Get over it! It’s been years.’ But you never get over somebody violently taking the life of your child. But this is a place where they can come. It’s what they need right now.”

Inside at the Christmas party, children were the first to come up to the cafeteria counter for a plate of spaghetti and meatballs, two chicken legs, and a big roll. Parents followed, helping themselves to mole sauce to go with their lunch. The steady hum of laughter and conversation coming from the two rows of tables was the sound of a family reunion, not a grief session.

Looking around the room, Valdez talked about plans to expand HHRH to focus specifically on helping children. She recalled a young girl whose sister was killed in a drive-by gang shooting years ago. Later, when she saw her, the girl couldn’t stop sobbing. She felt a guilt that had never gone away: She should have been outside to protect her 10-year-old sibling, she said.

“A lot of these kids never dealt with the homicide that suddenly came into their young lives,” she said. “And that’s why you see them having trouble concentrating and learning in school. A lot of times they’re nervous. They can’t sit still. So they get into trouble. They’re diagnosed with ADD [Attention Deficit Disorder].

“And a lot of it has to do with the trauma they’re carrying from seeing a close relative killed. So if we could work with children to be able to move beyond that and have a safe place for them, I think that would help them heal, and their parents as well. And parents could be aware of what happens to their children who experienced such a huge loss. So there’s education on all levels.”

After laying more of the groundwork, Valdez hopes to start the child-centered healing program this year.

‘Vicarious trauma’

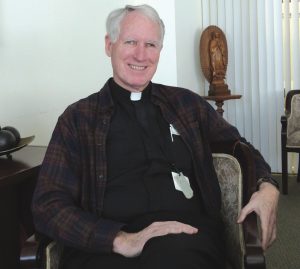

Father George Horan, former head of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Office of Restorative Justice, founded Healing Hearts Restoring Hope six years ago. After some three decades working in prison ministry, he saw a need that wasn’t really being met.

“I thought that the one aspect that was really missing was healing from the trauma of violence that a child experiences,” he said. “We would do all kinds of good programs inside of prisons and outside with victims. But we weren’t getting down to what really happens to children that brought them to the point where they could commit a violent crime like murder.

“What do they need to heal from their traumatic childhoods? What do people need to heal from the trauma that’s related to homicides?”

And that was one of the reasons why Valdez was hired: to design and implement a program geared for kids. But HHRH eventually went beyond those directly touched by violence to include others affected by homicide, including first responders, court personnel and jurors, as well as members of the community where the killing happened.

“We started to see the ripple effect of violence,” reported Father Horan. “There was an EMT [emergency medical technician] guy who picked up a 7-year-old boy who was shot in the head and took him to a hospital. And then quit. So he was a victim of that crime. What healing does he need now to deal with that?”

And then there were prosecutors, defense attorneys, public defenders, and judges who just do murder trials. They see the gruesome photos, hear the gory details all the time in their jobs, taking on what the priest called “vicarious trauma.”

The same applies to social workers at Los Angeles County Hospital+USC Medical Center and other hospitals with trauma care centers, who have to deal with the families of loved ones who die violent deaths.

HHRH has worked with these groups and others.

Looking around the decorated cafeteria at Dolores Mission, Father Horan mused about the stories the smiling families carried with them.

“Most of all these children and adults had a family member who was killed. But some have just seen people killed in their neighborhood. They witnessed it. And the vast majority of them never got any kind of help,” he said.

“Adults talk about it, and they can get the help they need. But a lot of times kids just don’t deal with it. They don’t have the language to talk about it. And according to studies, almost everyone in prison for murder, by the age of 10 had witnessed at least five acts of extreme violence, one of them being the murder of someone they loved.

“So what do they need to do to try to deal with all this trauma?” asked the priest. “That’s what Healing Hearts Restoring Hope is all about: helping all those affected by murder to heal from their trauma.”

A work worth carrying on

There were 253 homicides in the city of Los Angeles alone in 2019, meaning a ministry like HHRH will have its work cut out for it for years to come.

For the Bonillas, forgetting what happened has never been the goal. What the group has helped them to do, they say, is to heal with the help of a community.

“These other people in our group know, understand what we feel,” said Juanita, who now helps other families touched by homicides. “That is very important for healing. And on our journey to healing, it has helped my other children to be OK, too.”

“It’s given me the only hope of ever seeing my daughter again,” said Tomas. “I’ve promised God that I will be a good person with that hope. My faith has given me hope.”

For more information on Healing Hearts Restoring Hope, visit hhrh-la.org.