It is overcast and quiet as parishioners stream into Newport Beach’s Our Lady Queen of Angels Church, greeted by pastor Father Steve Sallot, both his grin and Roman collar askew.

Though it’s the 7 a.m. Mass, the flow of cars and people remains steady, perhaps because it’s Super Bowl Sunday and there are dips waiting to be layered. Or perhaps because this Mass, and at this parish, figures to be forever linked to the final hours of Kobe Bryant’s life.

In the immediate aftermath of Bryant’s sudden death along with eight other people, including his 13-year-old daughter Gianna, in a helicopter crash Jan. 26, it soon became known that Bryant stopped by Queen of Angels, located a couple miles from his Newport Coast home, for a few moments of reflection and prayer, leaving just 10 minutes after that 7 a.m. Mass started to head to John Wayne Airport.

Father Sallot later confirmed to various local news outlets that he had seen Bryant after he had prayed in the chapel.

“We shook hands, I saw that he had blessed himself because there was a little holy water on his forehead,” Father Sallot said. “I was coming in the same door as he was going out ... we called that the backhand of grace.”

Though Bryant was well-known for his discipline (Mamba Mentality), cosmopolitan ways (giving interviews in multiple languages) and, most of all, love, admiration, and devotion for his daughters (the trending hashtag #GirlDad among the tributes), the fact that Bryant took his faith so seriously seemed to take many, including those in the media, by surprise.

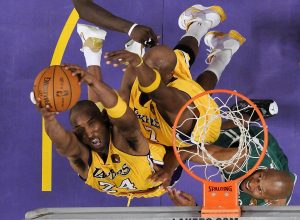

The media may have first met him as a star in Lower Merion High School in Pennsylvania before the Lakers obtained him in a 1996 NBA draft trade, but considering Bryant started living in Milan, Italy, at age 7, since his father, Joe, played seven seasons in the Italian League after his own NBA career ended in 1983, Catholicism seems to have been as natural a part of life as basketball.

Bryant was willing to talk about his faith with anyone willing or wanting to listen. It was there, he said, at both his highest and lowest moments.

When, by his own admission, he had allowed his life to spin completely out of control, being accused of rape in a Colorado hotel room, one of the first people he turned to was a Catholic priest, telling GQ magazine, “The one thing that really helped me during that process was talking to a priest.”

The day after his last NBA game, one in which he scored 60 points, he told an ESPN reporter that he celebrated by rising early, drinking a cup of coffee, and going to church.

“It was me, alone,” he said. “After 20 years, I think it’s important to give thanks.”

In 2001, Bryant married his wife, Vanessa, herself a Catholic, at St. Edward the Confessor Church in Dana Point. Father Sallot said that he and Kobe had chatted about his desire to receive the sacrament of confirmation in the future.

Though all of this may have been surprising to some, it certainly wasn’t to those at Queen of Angels who knew Bryant as a consistent and enthusiastic part of the faith community, one who regularly attended, many times sliding in as the entrance procession was halfway down the aisle, sitting in the back and leaving before the procession came back so as not to be a distraction.

Parishioner Dominic Picarelli said he’d seen Bryant often over the past 16 years, at the beach, at kids’ basketball games. He said he was perhaps most impressed at seeing Bryant consistently, session after session, as his daughter Natalia and Picarelli’s son, Ethan, went through the two-year process of first Holy Communion.

“He was always there. Always. Always for his kids,” Picarelli said. “You can always gauge a man’s character by the way he treats children. He showed such patience when he was around kids. I never had a chance to tell him that; I feel bad I never did.”

During his homily, Msgr. Wilbur Davis, known as Father Wil, talked to the assembled, which included one man wearing a black Bryant jersey trimmed in gold, about the feast of the Presentation of the Lord, when Christ was presented at the Temple. He reminded them that heaven is our eventual and “essential citizenship” which, as in Christ’s time, must be prepared for through sacrifice and daily practice of one’s faith.

Picarelli saw that with Bryant during two years of commitment to his daughter’s first Communion, attending often out of the public eye.

“I know most people will remember him for scoring 81 points,” Picarelli said. “I just remember he was a great dad.”

When the news of the tragedy began to permeate social media, a group of young basketball players and their parents, waiting at the Mamba Sports Academy in Thousand Oaks, dropped to their knees. Within hours, Southern California bishops on pilgrimage in Rome got word of the news and offered up their prayers.

“So very sad to hear the news of #KobeBryant’s tragic death this morning,” tweeted Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez within hours of the crash. “I am praying for him and his family. May he rest in peace and may our Blessed Mother Mary bring comfort to his loved ones. #KobeBryantRIP.”

Archbishop Gomez had first met Bryant in 2011, soon after becoming archbishop of Los Angeles, when he was invited to a Lakers team practice in El Segundo.

Nearly a decade later, the avid basketball fan gathered with his brother bishops from Los Angeles and Orange counties for a prayer service for the victims of the crash in the Blessed Sacrament chapel of the Papal Basilica of St. John Lateran.

“Had we been in Los Angeles or Orange, we would’ve probably been at some prayer services,” explained Auxiliary Bishop Timothy Freyer of Orange. “We wanted to let our people know, especially the families of the victims, that they are in our hearts. We thought to gather together and have a prayer service would hopefully be a way to give some consolation during the difficult time.”

Bishop Freyer found out about the crash Sunday night in Rome from a flurry of messages and e-mails on the eve of a week of meetings in the Vatican.

Priests assigned to that parish over the years had shared with Bishop Freyer how they’ve been inspired by Kobe’s humility.

“He would frequently wait until the entrance procession got at least part of the way down the aisle and he would just come in and go into one of the back pews so that he wouldn’t distract the people,” said Bishop Freyer in an interview at the Pontifical North American College in Rome. “He wanted people to focus on Christ’s presence, not his presence.”

Bishop Freyer believes Bryant deserves credit for having the same extreme determination he showed on the basketball court in “giving everything he could to save his marriage.”

“The practice of the faith wasn’t just to save the marriage,” said Bishop Freyer. “I think it was also a way for him to draw closer to Christ, and hopefully anybody in any state, whether it’s in a state of grace, whether it’s in a state of problems, discouragement, family troubles, sin, that they, too, would follow his example and turn to the Church and throw themselves at the feet of Christ.”

Those at the Pauline Center for Media Studies in Culver City had a special moment to reflect upon. Sister Rose Pacatte posted a short story on Pauline.org about the day in 2004 when Bryant visited:

“I wish I had been home that day. … He was looking for a special rosary for his wife, Vanessa. As the sister who was there tells the story, the other shoppers stopped and looked in awe as he moved quietly around the shop.”

The sisters recall that the visit came soon after the dismissal of his rape accusation case in Colorado. He and his accuser would later settle a civil case out of court that included a public apology from Bryant.

“Bryant eventually purchased two very nice rosaries that day,” the sister wrote.

“As he turned to leave, a small grandmotherly-looking lady walked up to him and tilted her head up, way up.

“ ‘Mr. Bryant?’

“ ‘Yes, ma’am?’ he replied as he looked down to meet her gaze.

“ ‘I just want you to know,’ she said solemnly, ‘I pray for you.’

“He paused a moment and said, ‘Thank you, ma’am.’ ”

Sister Nancy Usselmann, a Daughter of St. Paul who is a director at the Pauline Center, said stories posted on social media during a time like this can be beneficial on many levels.

“I think it is significant when a celebrity such as Kobe connects deeply to their Catholicism and what an influence for good that can have on a culture that often emphasizes the negative and sensational about celebrities’ lives,” she said.

“This story and all the social media stories that are coming forward show a man humble enough to know that having all the fame and fortune of this life is never enough when it comes to humanity’s deepest yearnings and desires,” she added. “We long for more. That’s how we are made. We ultimately and unconditionally long for God, whether we pay attention to that inner hunger or not.

“Kobe’s expressed Catholicism makes that clear in a world that tries to push down that hunger, social media can be that outlet that sends this message out quickly.”

Sister Usselmann believes that such a loss can help people face the fear of death more honestly.

“It is hard to grasp the ‘why’ in such a tragic death of a celebrity, but we believe that in this, too, God has a plan,” Sister Usselmann told Angelus News. “The fact that he was at church not long before that flight is a great consolation that even in our mistakes of our past, God reaches out to us, longing to have us to himself and will take every opportunity for us to draw close to him. We just need to listen. Thankfully, Kobe listened.”

Social media posts also flashed back to interviews Bryant did over his 20-year playing career.

One was a clip of him in 2006 being interviewed by ESPN host Stephen A. Smith, who asked him what he had learned from the sexual assault accusation episode.

“God is great,” Bryant said.

“Is it that simple?” Smith pressed him.

“God is great. Don’t get no simpler than that, bro,” he replied, pursing his lips.

“Everybody knows that,” Smith responded, “but the way you know it now, did you know it before that incident took place?”

Bryant cocked his back in something of an assured confidence.

“You can know it all you want,” he said, “But until you got to pick up that cross that you can’t carry, and he picks it up for you and carries you and the cross, then you know.”

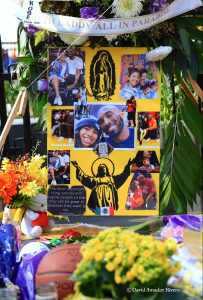

Appropriately, crosses were among the most common items left at the makeshift memorial in the L.A. Live plaza across from Staples Center that seemed to expand by the day, with flowers, balloons, basketballs, stuffed animals, illustrations, and even personal messages scrawled on the plaza floor tiles.

The Catholic-themed icons included large jar candles with images of Jesus, St. Joseph with Jesus, or the Virgin of Guadalupe. Rosaries were draped on Bryant family photos.

One white-beaded rosary glistened as if it was lit up by the sunlight hitting it.

A poster distributed by one fan had a photo of Kobe and Gianna Bryant with the Scripture verse from John 11:25: “I am the resurrection and the Life. The one who believes in me, even if he dies, will Live.”

Lee Zeidman, president of Staples Center, L.A. Live and Microsoft Theater, said Bryant’s wife, Vanessa, reached out and asked if the family could have the items. Zeidman said they would be catalogued and shipped to them after they were collected Sunday night, Feb. 2.

One fan taking in the whole event said he couldn’t help but think of a passage from Matthew 25.

“So, Kobe was the GOAT (Greatest of all Time), right?” he said. “There is that Bible verse about how some day we will all be separated, sheeps from goats. Sheeps go to heaven, right? … But if Kobe was the GOAT, hey, maybe they can make a special case for him.”

Editor-in-Chief Pablo Kay also contributed to this story.