Deborah Tobola is known as a visionary pioneer in the field of arts in U.S. corrections.

She is a graduate of the University of Montana, and has a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from the University of Arizona. Her prose and poetry have won several awards. She has worked as a waitress, journalist, legislative aide, and adjunct English faculty member in Alaska and California.

She currently serves as executive director of The Poetic Justice Project, an organization that “advances social justice by engaging formerly incarcerated people in the creation of original theatre that examines crime, punishment, and redemption.”

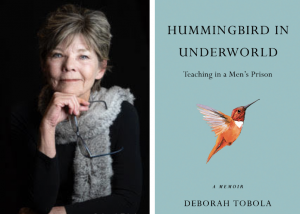

“Hummingbird in Underworld: Teaching in a Men’s Prison,” out this year from She Writes Press ($17), is ostensibly an account of Tobola’s nine-year tenure at the California Men’s Colony (CMC) in San Luis Obispo.

But this mesmerizing hybrid is much more: part family memoir, part prison system snapshot, partly a narrative of the making of a poet.

Her father, a ranch boy from California’s Antelope Valley desert with Bohemian roots, was working as a guard at CMC when Tobola was born. One of her earliest memories is the day he invited her, her mother, and her 2-year-old sister Bonnie to eat at the prison cafeteria. “Daddy, I like eating at the Joint!” she reported. She was three at the time.

The family moved often: Shell Beach, Fresno, Lancaster.

Her father was a hard-drinking, fun-loving, rough-around-the-edges thinker and dreamer, and Debbie was his girl.

She remembers a Christmas family reunion when she was 11. The “Bohunks” — her father and male relatives — “didn’t scare me, the way they did my sisters. I was the only girl in the family they claimed as one of them. I learned the ways of their world, talking politics, pounding my fist on the table, entertaining people with stories. Perfect training for a career working with rough men given to outbursts verging on violence.”

The ensuing decades weren’t easy. Her first teenage marriage was annulled. Her son Joseph was four when his father was killed in a motorcycle accident. Her third marriage produced a son, Dylan. That union ended in divorce as well, a year after her father’s death.

In 2000, when she started at CMC, she already had five years’ experience, teaching prison inmates in Tehachapi and Delano. It was her dream job. She’d been hired to run Arts in Correction, the prison’s fine arts program.

Her first week on the job, she mistook an inmate drawing of a guard tower for a lighthouse, an emblem of hope.

Still, she couldn’t afford sentimentality. She had her students’ backs: Opie, the gentleman robber junkie; Smiley, a child molestor (one of many); Sal, a poet and painter serving a life sentence for murder; Razor; Alejandro.

But she never allowed herself to be played. It went without saying that the prison system suffered neither fools nor victims gladly. It also went without saying that the system was often heartless, often senseless, always hard, and harder still on the women who worked within it.

Tobola didn’t dwell on those facts. She accepted them from the start and with a backbone stiffer than most, quietly, doggedly devoted her life to bringing art to the incarcerated.

In fact, in one compelling chapter she describes Petter, a leader in experimental theater from Denmark who offered to travel to CMC and put on a workshop. Tobola was thrilled. Here, at last, was perhaps the shot in the arm her program needed to avoid the “budget butchers.”

Petter’s visit was a disaster. His artistic sensibilities offended, he spent his time contemptuously criticizing the American prison system. Tobola herself had no time for such nonsense. Her focus was forever on the inmates, not herself.

Together, and with Tobola’s guidance, the students created, wrote, and staged original theater. They won writing awards and published their work locally. The community turned out in droves, inspired and moved. Tobola begged, borrowed, scrimped, improvised, gave tenfold, we intuit, what her job description required and what she was paid for.

She wrote wrenching poems about her time at the prison and the inmates, several of which are included.

And after all that, in the end her programs were eliminated due to budget cuts.

She retired in 2008 to start the Poetic Justice Project, and returned to CMC several years later to teach creative writing and theater.

Her students are lucky to have her. She never blows her own horn, allowing herself but a single terse note of self-congratulation: “I’ve never been a quitter.”

On one level “Hummingbird in Underworld” is a narrative of teaching art in prison. On another, the book is a memoir of vocation, that we are formed by our families is the subtext: for better, for harder, for good.

The lengths to which Tobola will go for her students are stirring, astonishing, heart-rending.

But perhaps the real heart of the book is the Christmas family reunion that in her memory remains “as vivid today as when I was 11.” The night ended in a drunken fistfight, and then reconciliation.

“The men were laughing and crying, hugging each other, saying ‘sonofabitch.’ They drew me into their circle and closed it. I cried too, alive with their terrible love.”