Through Nov. 10 at the Getty is a compelling exhibit based on the work of Gordon Parks, a Renaissance-man film director, writer, and photojournalist perhaps best known for his work for LIFE magazine.

President John F. Kennedy’s “Alliance for Progress,” launched in 1961, was an initiative designed to promote democracy and economic cooperation across Latin America and to forestall the spread of communism.

In March of that year, LIFE sent Parks to Rio de Janeiro with the assignment to document the country’s poverty.

At the time, the city’s more than 200 garbage-strewn favelas — hillside slum towns — were home to an estimated 700,000 people. The average per capita income was $289. Parks, a Kentucky native, had grown up poor himself, but had never seen destitution of such a degree and kind.

He spent several weeks in a favela called Catacumba. The resulting photo essay, “Freedom’s Fearful Foe: Poverty,” appeared in LIFE’s June 22, 1961, issue.

The piece featured the da Silva family: father José, an injured construction worker forced to sell kerosene and bleach from a tiny stall; mother Nair, who earned money by scrubbing laundry beneath one of the favela’s few spigots; and their eight — soon to be nine — children.

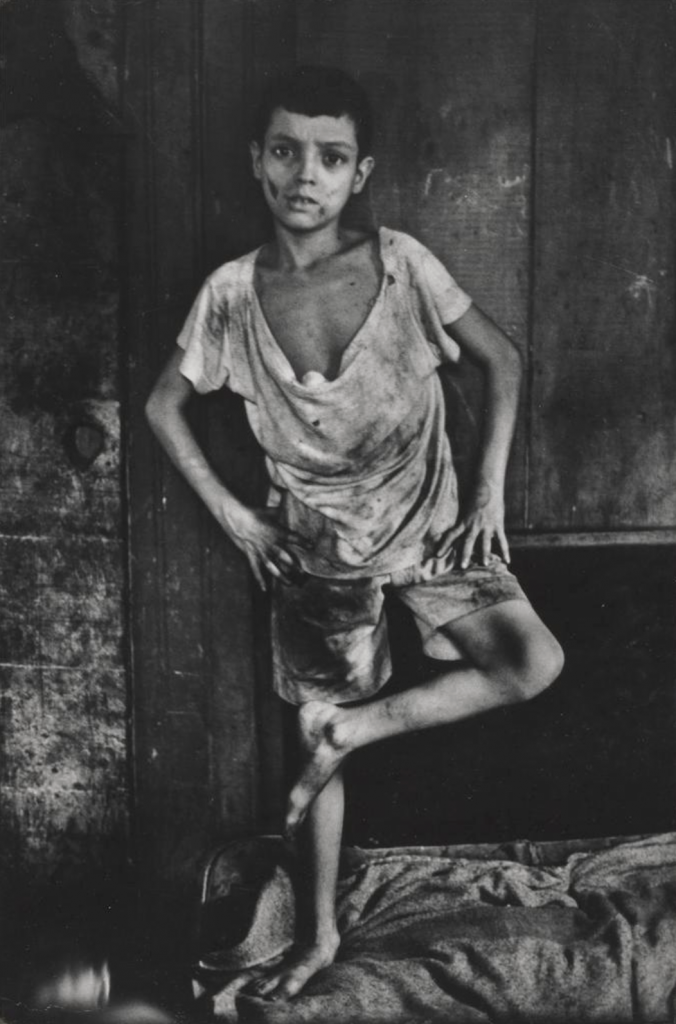

Flávio, the oldest at 12, functioned as a de facto surrogate parent, hauling water, cooking, cleaning, disciplining, and babysitting. He also suffered from a wracking case of asthma.

You’ll recognize some of these photos. The tiers of shanties, spilling off the hillside, with a cross looming above. Flávio spot-lit on a bed, torso bare, lying beneath a filthy blanket with arms outstretched as if being crucified. Mario, a younger brother, howling in pain after being bitten by a stray dog.

The text described the da Silvas’ struggles, Brazil’s economy, and the tensions between communism and capitalism.

The piece was a sensation. Within days of its publication, money started pouring in from concerned readers, and Flávio was invited to receive treatment at the Children’s Asthma Research Institute and Hospital (CARIH) in Denver.

The July 21, 1961, issue of LIFE was entitled “Flávio’s Rescue: Americans Bring Him from Rio Slum to Be Cured” and pictured a grinning boy in fresh pajamas clutching a stuffed Snoopy.

Some of the donations also went to improve the infrastructure of the favela and to relocate the da Silva family to the nearby suburb of Guadalupe.

Progress, of a kind, but with an undercurrent of sorrow running through.

In “Flávio” (1978), for example, Parks later described the scene the day the da Silvas left the slum.

“One woman came forward and kissed Zacharias [one of the younger children], then Nair, then turned back up the hill in tears. Another woman standing by with a small child in her arms grabbed my shoulder.

“ ‘What about us? All the rest of us stay here and die!’ she demanded.”

The Brazilian media bitterly resented Parks’ depiction of the country’s endemic poverty. In retaliation, the magazine O Cruziero sent photographer Henri Ballot to Manhattan to document a Puerto Rican family living in squalor on the Lower East Side.

Meanwhile, Parks agreed to accompany Flávio to Denver. The boy received treatment (doctors reported that he had the weight and height of a six-year-old), largely recovered from his asthma, and learned English. He lived at CARIH until the summer of 1963 and was greatly assisted by his weekend host family, the Gonçalveses.

Flávio was charismatic and a quick learner. But eventually Parks realized that all the love and medical care in the world couldn’t undo 12 years of poverty and hardship. “The truth was inescapable. We had dreams for Flávio da Silva that were hopelessly beyond his reach. It was as if we expected abundant fruit from a sapling already gone barren.”

And when the inevitable time came to return to Brazil, Flávio was devastated.

He went on to marry and the couple had two sons. But in photos of him as an adult, he retains the haunted, thousand-yard stare of a shell-shocked war veteran.

By 1970, Catacumba had been razed to make way for more profitable construction, and 13,000 residents had been forcibly relocated to makeshift housing outside the city.

Parks and Flávio reunited twice, once in 1967, and again in the late 1990s. Parks died in 2006.

Today, Flávio has retired from his job as a security guard and still lives in Guadalupe.

“[My story] is not a movie,” he observed recently, “but it was shot on film. [Gordon Parks] chose me. Now people know more about my life than I do. I’m glad that I’m alive as a result … this story never made me feel either better or worse than anyone else.”

Maybe not, but the telling of it opened eyes and hearts the world over.

In our time, we have Pulitzer Prize-winner Katherine Boo’s “Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity” (2012). Her Flávio was Abdul, a boy who supported his family of 11 by working as a garbage picker.

“When I settle into a place, listening and watching,” Boo wrote of her time in the slums, “I don’t try to fool myself that the stories of the individuals are themselves arguments. I just believe that better arguments, maybe even better policies, get formulated when we know more about ordinary lives.