The U.S. welcomed 250,000 Salvadorans seeking refuge from violence and natural disasters. They have called this country home for more than a decade. Now, the government wants to send them back.

“Why? I have never, never had problems with the police. I pay my taxes. I pay almost $500 every 18 months for my TPS. I am very honest. Very good person. My boyfriend of 26 years is in same situation. And my daughter born here has no protection at all. But my grandkids are American citizens. They were born in America.”

Guadalupe, who doesn’t want her last name mentioned, pleads again, “So, why now?”

The 57-year-old immigrant lives near downtown L.A. with her longtime boyfriend. Both are from El Salvador. Because she is a TPS (Temporary Protective Status) holder, she’s able to work legally in the U.S. And she does for 11 hours every weekday as a nanny and housekeeper for a family in Beverly Hills. She makes $700 a month. And a lot of that goes back to relatives in El Salvador, to where she has never returned.

“Why is that?” she’s asked.

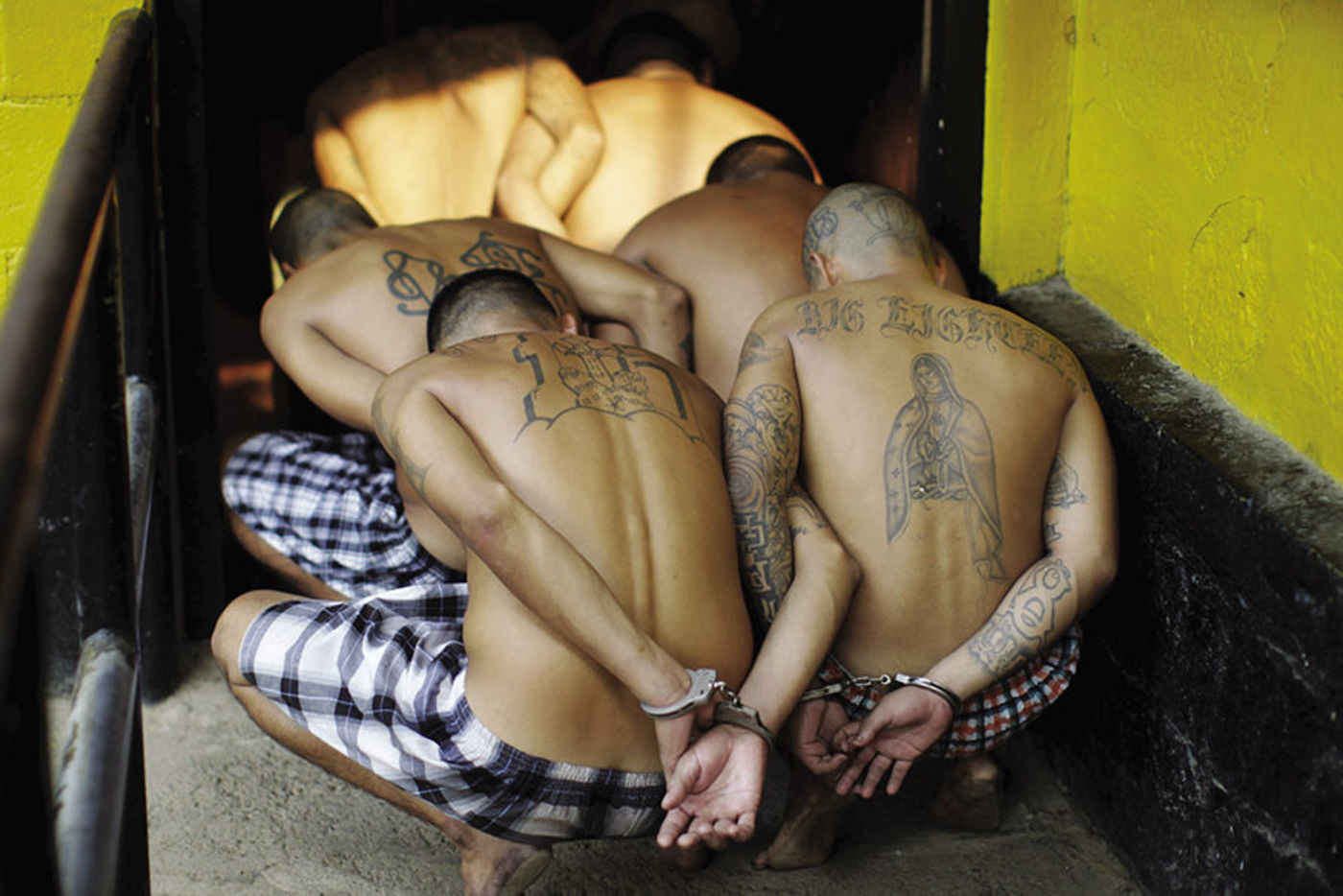

“There is no work over there and there would not be a job for me,” she says. “My country is very poor. My country is terrible. The gangs are there, drugs are there. My country is so bad now. The people in the government take it all. They are bad people.”

After a moment, the hard-working immigrant confides, “I’m very nervous. I’m very worried. I don’t know what will happen. Maybe things will change back and we can stay in America. I don’t know.”

Guadalupe is one of 262,500 Salvadorans who have protective status to live in the United States.

President George W. Bush opened up the program to Salvadorans after the small Central American nation was devastated by two hurricanes in 2001. Nearly 1,000 people died. More than 100,000 homes were destroyed.

The purpose of TPS has basically remained the same since Congress passed and President George H.W. Bush signed the legislation as part of the Immigration Act of 1990.

Its purpose was — and still is — humanitarian: to provide temporary sanctuary to immigrants in the U.S. who are “temporarily unable to safely return to their home country” because of ongoing armed conflict, natural disasters or other extraordinary and temporary harsh conditions. Under the program, immigrants are allowed to live, and work, here.

President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama continually renewed the program every 18 months for the Salvadorans. But on Jan. 8, the Department of Homeland Security ended TPS for the Salvadorans, many of whom have been living in the United States for almost two decades.

A statement from Homeland Security simply said: “The substantial disruption of living conditions caused by the earthquakes” no longer exist. The Bush and Obama administrations repeatedly found that not only the country hadn’t fully recovered from the quakes, but that raging violence, gang activity and drug cartels prevented Salvadorans from safely returning home.

The decision, which takes effect next year, came on the heels of the administration ending TPS for refugees from Haiti (50,000), Nicaragua (2,500) and Sudan (1,000).

rn

rn

rn

Gangs and poverty

“To be honest, I’m afraid,” says Joana during an interview with Angelus, who also wants to remain anonymous. “I went back and everything was very different from what I remember. I do not see me living there. I mean, there is so much crime going on. There’s a lot of gang stuff going on. The little town that I’m from is safe enough. But even if you live in a gated community like some of my relatives, they still face danger going to their jobs or anything else. It’s still not safe. Like, MS-13 is one of the biggest gangs. But even in smaller cities, there’s rivals between gangs, just like there are here.”

There’s another reason the 28-year- old, who is close to getting a graduate degree, can’t imagine returning to live in El Salvador. And it’s concerned with just making a living in a country split mostly between the very wealthy and the poor.

“What am I going to do with my master’s in social work?” she says. “I mean, there’s a lot you can do in a humanitarian way. But to survive and to have a stable lifestyle, I can’t do that in my little town. Not compared with the opportunities that I find here.

“So when I heard the news about TPS coming to an end next year, it was disheartening to say the least. It was a very difficult day for me and my family, because we have different statuses here. We live around each other in the Echo Park area. And our big fear is that we’ll be split up.”

There’s just one number you need to know to understand how this family fears becoming more real with the ending of TPS for Salvadoran immigrants next year. The figure is 193,000. That’s the number of American-born U.S. citizens TPS parents have given birth to since 2001.

The Department of Homeland Security was recently asked if Salvadoran parents must leave their U.S. citizen children behind. A senior administrator remarked, “We’re not getting involved in individual family decisions.” But it’s more than safe to say the Trump administration’s new policy will tear apart tens of thousands of these immigrant families.

Vanessa, like Guadalupe and Joana, didn’t want to give her last name. The sociology major at California State University, Northridge, has mixed thoughts about her close-knit family’s sudden precarious situation. Vanessa, her brother and three sisters were raised by a single mom after coming to the U.S. That was 17 years ago. What would they do now if there’s no change from Congress or the president on TPS?

“We are definitely not ready for that time to come,” she admits. “I mean, our family won’t be split, because we would all go together.” But then she adds, “I’m not going anywhere. If it has to come down to them coming and looking for me, then it is what it is. But for me to say, ‘Oh, yeah, it’s done here. I have to go back,’ that’s not for me. It’s like this is my home.”

She talks about how hard her mother has worked to pay nearly $500 every 18 months for each of her children and herself to keep up their TPS status.

“When I heard the decision about ending TPS, I was like ‘wow!’ This is actually happening,” she says. “I remember it was a gloomy day. And then it just made me really sad and scared for the future. Really scared. Like at that moment, I just lost hope. It’s sad to think about going back, ’cause I was only four when we left, so I don’t know anything about El Salvador. I don’t speak very good Spanish. And I don’t dress like them.

“So I’d be a target for the gangs: ‘She and her family aren’t from here. They must have money.’ So I’m not going back.”

rn

rn

rn

“Heartbreaking”

On the same day Homeland Security announced protective status for Salvadorans was ending, U.S. bishops spoke out strongly against the decision. They pointed out how the new policy will force immigrant parents to make a very hard decision: either to separate from their U.S.-born citizen children, or take them back to a troubled country where young people face threats of gang violence and poor schools.

“This decision to terminate TPS for El Salvador is heartbreaking,” said Bishop Joe S. Vasquez of Austin, Texas, who chairs the bishops’ committee on migration. “El Salvador is currently not in a position to adequately handle the return of the roughly 200,000 Salvadoran TPS recipients. Today’s decision will fragment American families, leaving more than 192,000 U.S. citizen children of Salvadoran TPS parents with uncertain futures. Families will be needlessly separated because of this decision.”

Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez called for a permanent path to residency and citizenship for the Salvadoran immigrants. “In the meantime, the Catholic community will continue to walk with our brothers and sisters from El Salvador, opening our hearts to their families in love and charity, and welcoming the gifts they bring to this great nation,” he promised.

rn

rn

rn

So is the “heartbreaking” decision, which has been largely overshadowed by DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), which is before Congress with it ending in months, a done deal?

Dalia Cuevas doesn’t think so. Her own case, going from an illegal immigrant with a deportation order to a TPS recipient and to finally being able to apply for a green card, was extremely complicated. So much so that for a decade she searched for a lawyer who would take it. She finally found one in 2016 who was able to reopen the case. Recently, she had a court appearance before a judge. He ruled it wasn’t her choice to come into the U.S. illegally and dismissed the deportation order.

And this week, she was finally able to apply for a green card that, hopefully, will give her lawful permanent residency in the United States.

“So people shouldn’t give up,” says the 29-year-old. “My mom always told me we have to do something about my status here. It’s going to happen. So that’s what kept me wanting to keep working and keep striving to be a citizen. I’m super happy for myself, but I’m sad for all the other kids with TPS. They’ve been hopeful for all these years going to school and becoming a good person who contributes to society, being more American than Americans sometimes.

“And now they might be sent back to El Salvador next year, which they probably know nothing about,” adds the native Salvadoran, who now works at a credit union in Southern California. “But they should keep trying. It took me 10 years to find a lawyer to take my case. They should keep trying.”

For Salvadorans in L.A., TPS help and information

The Salvadoran Consulate and Archdiocese of Los Angeles announced on Jan. 18 there will be free TPS (Temporary Protective Status) informational presentations for applicants of the program in Los Angeles, San Fernando and another location. The presentations will be led by Catholic Charities of Los Angeles and SALEF (Salvadoran American Leadership and Education Fund).

Updates on a number of topics will be held, including: understanding your legal status; where to find trusted legal sources; Department of Homeland Security actions on TPS and DACA (Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals); next steps, including other immigration options; and how to avoid immigration fraud and being a victim of notaries.

“The counselor of El Salvador and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles saw the need to help out the community and make sure TPS holders understand the importance of being able to renew their TPS while our [government] administration has decided to end the program,” said Isaac Cuevas, associate director of Immigration Affairs for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. “That doesn’t mean that the program is over. It means that the program is in the process of ending.”

Cuevas stressed the “importance that every single person who is a TPS recipient reapply for this last stage of TPS. Without this application for the last stage of their TPS, they may not qualify for another type of immigration status.”

Presentations will be held on the following dates and locations:

• Monday, Jan. 29, 6-9 p.m., St. Thomas the Apostle Church, 2632 W. 15th St., Los Angeles.

• Saturday, Feb. 3, 4-7 p.m., Santa Rosa Church, 668 S. Workman St., San Fernando.

For more information, contact Catholic Charities of Los Angeles at 213-251-3486, or email [email protected].

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.