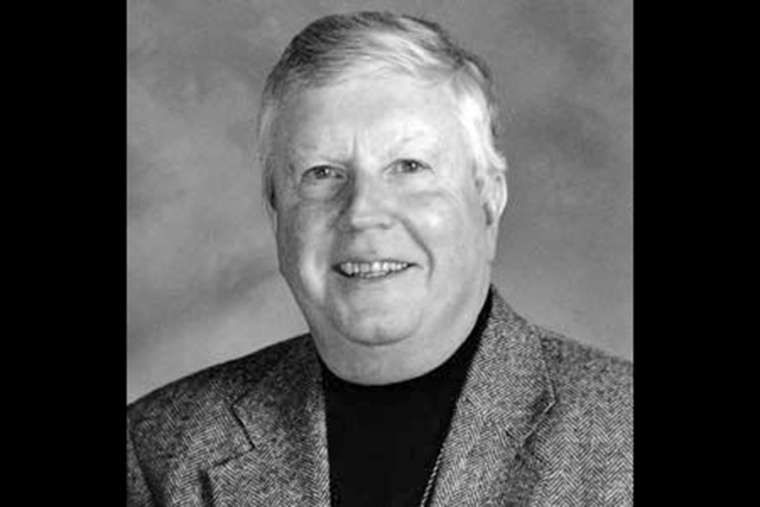

An intimate remembrance of the late moral theologian (1929-2018)

“We are all students of Grisez now.” The man who said that several years ago was a Catholic theologian not generally seen as being a disciple of Germain Grisez. He was simply acknowledging the influence Grisez had already had on serious students of moral thought — an influence that, one might add following Grisez’s death, seems likely to continue growing for a long time to come.

Grisez, a cherished friend with whom I was privileged to collaborate in writing several books, once gave me a striking indication of that. Interviewing him for a profile of him that I was writing, I asked whether he could point to any impact he’d had on the thinking of the pope of that day, Pope John Paul II.

Yes, he said. He then cited the landmark 1993 encyclical on moral principles, “Veritatis Splendor,” where Pope John Paul discusses human goods as fundamental principles of morality (something new in a document of the papal magisterium), and the encyclical’s treatment of the beatitudes as embodying a vision of the moral life meant for all Christians without exception. Both things are major elements in Grisez’s moral theory.

rn

rn

rn

He was born in Cleveland and studied there at John Carroll University, at the University of Chicago, where he received his doctorate in philosophy, and at the Dominican house of studies in River Forest, Ill., where he pursued his interest in the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas.

He taught at Georgetown University, Campion College in Regina, Saskatchewan, and, for 30 years before retiring in 2009, at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland. He died Feb. 1 at the age of 88.

In the preceding half-century, he’d produced a stream of notable articles and books. Among the latter is a work that constitutes a virtual Summa of moral theology — “The Way of the Lord Jesus,” whose three volumes, published between 1983 and 1997, and totaling nearly 3,000 pages, contain the definitive statement of his thought.

He also was co-founder, with John Finnis of Oxford University and Notre Dame, of a new school of moral thinking generally referred to as the New Natural Law Theory.

Grisez was intensely loyal to the teaching of the Church. But that very loyalty, he believed, obliged him to critique inadequate arguments sometimes put forward in defense of Church doctrine, and then to provide other, better arguments of his own.

This he conscientiously attempted to do, starting with his first book, “Contraception and the Natural Law.” Published in late 1964, more than three years before Pope Paul VI’s encyclical “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”) with its condemnation of contraception, the volume defends Church teaching against artificial birth control while expounding a new approach to moral reasoning that centers on respect for human goods.

Much of Grisez’s contribution can be found in his books and articles on subjects like abortion, euthanasia, nuclear deterrence and personal vocation. But his influence also was exerted quietly.

That included writing, at the request of a cardinal, a detailed critique of a draft of the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

The cardinal submitted Grisez’s voluminous comments to the CCC’s drafters. The result was a catechism significantly stronger and clearer than it otherwise might have been.

He was buried in a hillside cemetery in Emmitsburg, Maryland, close to his wife, Jeannette, to whom he was intensely devoted, and one of their four sons, Joseph, who died young. The cemetery is near the seminary where, along with teaching seminarians, he wrote the works that, as the theologian quoted above remarked, make all of us “his students now.”

Hearing God’s personal call

rn

rn

rn

All Christians are called to holiness, and to the same heavenly hope. But God also calls everyone with his or her own personal vocation: a unique share in the Church’s mission, a personal way of following Jesus.

Each person is given the special graces needed for his or her particular apostolic life, so that by living a life of witness, he or she can cooperate with the Spirit in building up Jesus’ body.

What God said to Jeremiah he says to each of Jesus’ disciples: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you; I appointed you a prophet to the nations” (Jer. 1:5).

Personal vocation should embrace every part of one’s life, and care should be taken to discover and commit oneself to all its elements. The whole of life should be shaped by faith and hope, and no part of it should remain outside one’s vocational plan.

One’s gifts and opportunities are no accident. God provided them in view of his goal, the kingdom, which includes each person’s own true fulfillment, and in no way conflicts with it.

Christians who ask God, “What is your creative, fatherly plan for my life?” will find the elements of God’s reply in the appeal of values, the needs of others, and the gifts and talents they discover in themselves.

A Christian life, properly organized by the principle of personal vocation, includes every sphere of activity. It has a place not only for work and prayer, attending to the necessities of life, and sleeping, but for hobbies and recreation, celebrations, visits with friends, and so on.

Everything one has is a divine gift, to be used as God intends, so all of it should be put to use as efficiently and fully as possible in carrying out one’s vocational plan.

Faithfulness excludes holding anything in reserve for the use of an uncommitted part of the self, or thoughtlessly wasting material resources, energy, or time. Many people, for example, waste much of their time and energy in pastimes which, while perhaps sinless in themselves, bear no real fruit either for themselves or others: daydreaming, useless worrying, idle chatter, and passive entertainment.

Committed Christians should discipline themselves to replace useless activities with others that not only promise real benefit but further one or another element of their vocation.

The ideal of faithfulness is set in the exhortation: “Whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him” (Col 3:17).

From childhood until death, an individual should listen for God’s personal call, shaping and reshaping his or her life according to faith and hope, and living each day with love.

— Germain Grisez, “The Way of the Lord Jesus,” vol. 2 (Franciscan, 1993)

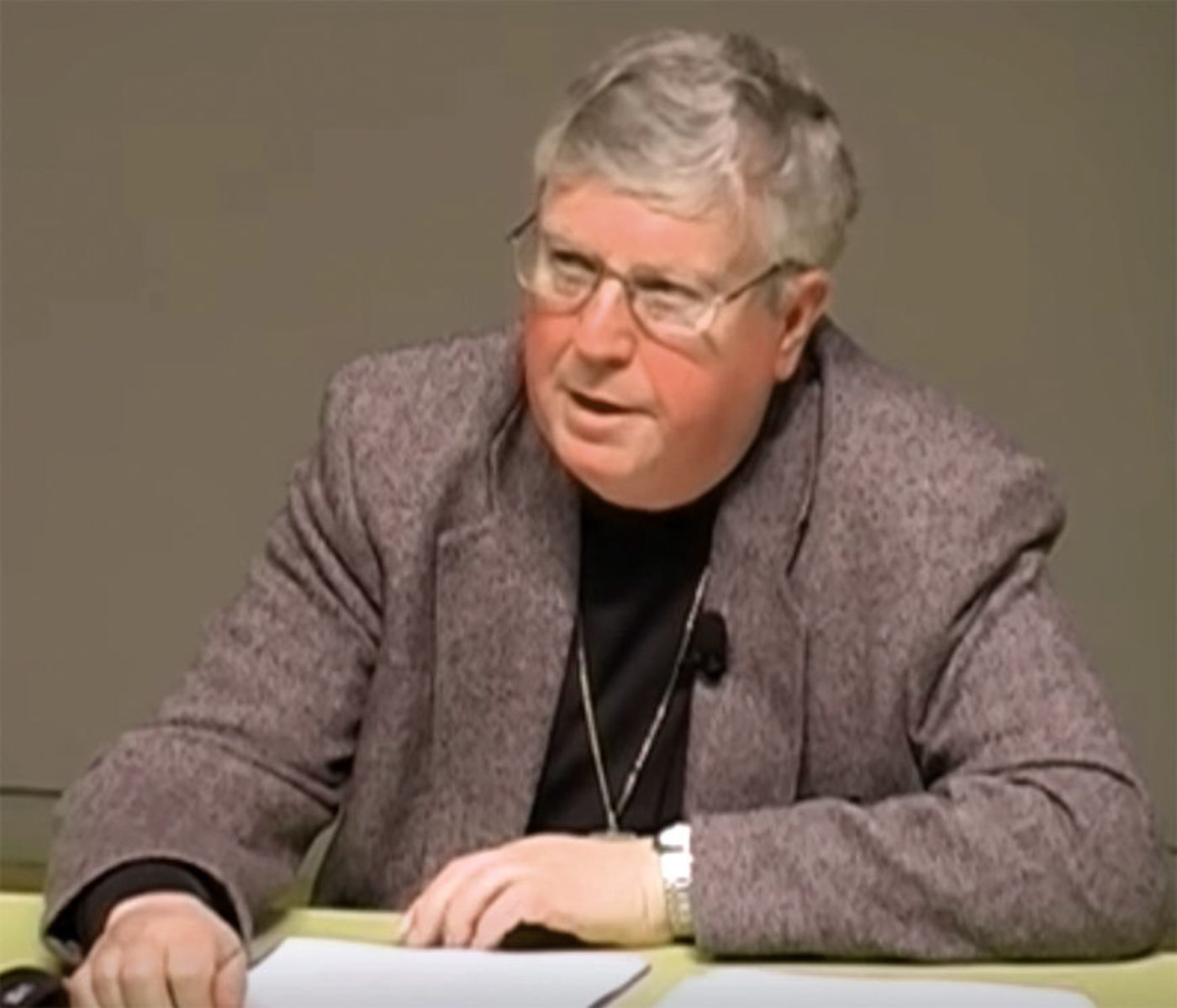

Russell Shaw is considered the dean of Catholic journalism in the United States. In a career that spans more than five decades, he has published thousands of articles and more than 20 books, including “Writing the Way,” “Papal Primacy in the Third Millennium” and his most recent, “Catholics in America: Religious Identity and Cultural Assimilation from John Carroll to Flannery O’Connor” (Ignatius, $16).