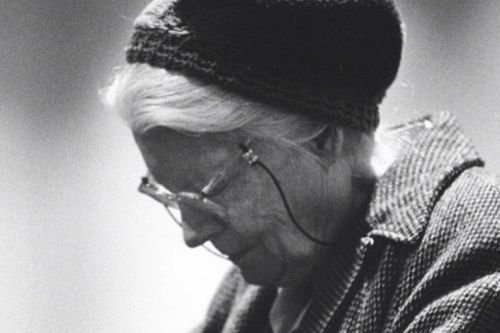

A new stage has begun in the process toward possible canonization for Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker Movement.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York has opened the canonical “inquiry on the life” of Dorothy Day, the archdiocese announced April 19. Starting this week, the archdiocese will interview some 50 eyewitnesses who had firsthand experience with Dorothy Day. Their testimonies and other evidence will be collected, examined to determine whether Day lived a life of “heroic virtue,” and will eventually be presented to the Vatican’s Congregation for the Saints and to Pope Francis.

In addition, Cardinal Dolan will appoint experts to review the published and unpublished writings of Dorothy Day, considering their adherence to doctrine and morals.

George B. Horton, liaison for the Dorothy Day Guild, noted that this will be an extensive project.

“Dorothy Day created or inspired dozens of houses of hospitality throughout the English-speaking world, but she was also a journalist who published The Catholic Worker newspaper,” he said.

“Her articles in that paper alone total over 3,000 pages. Add her books and other publications and we will probably surpass 8,000 pages of manuscripts.”

Born in Brooklyn and eventually raised in Chicago, Day was baptized Episcopalian at the age of 12. She displayed signs at a young age of possessing a deep religious sense, fasting and mortifying her body by sleeping on hardwood floors.

Her life soon changed as the 1910s brought about a stark shift in the U.S. social climate. A key turning point in her life and personal ideology came when she read “The Jungle,” Upton Sinclair's scathing depiction of the Chicago meat-packing industry.

Day dropped out of college and moved to New York, where she took a job as a reporter for the country's largest daily socialist paper, The Call. After fraternizing with the Bohemians and Socialist intellectuals of her time — and after a series of disastrous romances, one of which included an abortion that she later deeply regretted — Day fell in love with an anarchist nature-lover by the name of Forster Batterham.

She eventually settled in Staten Island, living a peaceful, slow-paced life on the beach with Batterham in a common law marriage. Conflict arose, however, when Day became increasingly drawn to the Catholic faith — praying rosaries consistently and even having their daughter, Tamar, baptized as a Catholic. Batterham, a staunch atheist, eventually left them and Day was received into the Catholic Church herself in 1927.

She returned to New York City as a single mother where her deep-rooted and long-standing concern for the poor resurfaced. Along with French itinerant Peter Maurin, she founded the Catholic Worker Movement in 1933. Living the Catholic notion of holy poverty and practicing works of mercy, the two started soup kitchens, self-sustaining farm communities and a daily newspaper. In the course of her 50 years working among the poor and marginalized, Day never took a salary.

Her legacy lives on today in some 185 Catholic Worker communities in the U.S. and around the globe.

In a 2012 meeting of U.S. bishops, Cardinal Dolan called Dorothy Day “a saint for our time,” describing her as “a living, breathing, colorful, lovable, embracing, warm woman who exemplifies what’s best in Catholic life” and shows the Church’s commitment to both the dignity of human life and social justice.

The Vatican opened the canonization process for Dorothy Day, naming her a “Servant of God,” in 2000.

The road to canonization is a lengthy one, normally requiring many years and several stages, including examination by a diocesan tribunal and a Vatican congregation, as well as the approval of two miracles attributed to the saint’s intercession. Ultimately, the Pope has the final say in canonizing saints.