In a world obsessed with what we can touch, see, measure, and record, beauty and truth are less important than ever to modern man. His outlook is largely horizontal, and having a spiritual outlook on life is harder than ever.

But even so, as the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins once put it, the natural “world is charged with the grandeur of God.” The narrowest contemporary mind can’t help but be moved by the glints of that grandeur “shining like shook foil” when for a moment it looks up from the pavement at the glimmering sky.

By looking up, man can start to experience that there’s something even grander than our flattened, human world: a spiritual world in which our souls are engaged in an important battle, unseen but not unfelt, in which immortal forces are fighting either on our behalf or against us.

In other words, believing in angels matters.

Even though angels color the traditions and narratives of several major religions, modern theology has persistently trivialized them, dismissing them as psychological symbols and cultural metaphors.

That’s why a new book from Cambridge Professor Michael D. Hurley, titled “Angels and Monotheism” (Cambridge University Press, $22), comes at an important moment.

The professor’s book is an attempt to reinvigorate the discipline of “Angelology.” I confess this is a strange and unexpected word, but the concept — that angels exist and their position and function within the Divine Order is something to study and digest — is sound. If God has in fact provided powerful assistants for each of us in our daily spiritual struggle, it would be madness to disregard them or sentimentalize them into insignificance.

Hurley, a professor of theology and literature, explains some of the difficulties contemporary theologians have when it comes to angels. Many are caught between faith and their desire for scholarly respectability in a world in which faith and reason are considered antagonists.

He refutes the leading attacks against angels as being mere extra-scriptural speculation, the poetic effusions of the human imagination, or a piece of knowledge relying for legitimacy on Divine Revelation. He shows that the existence of demons and angels may not be the very heart of the Christian faith, but it is certainly an objective truth, within the order of revealed truths that all Christians are bound to believe.

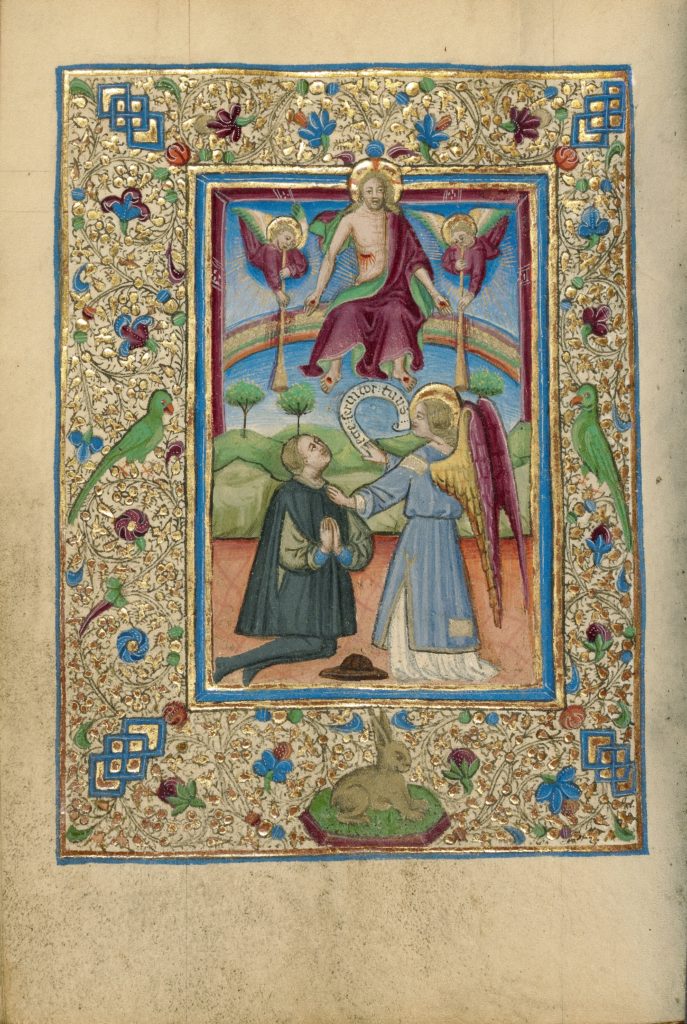

If bound to believe, then we are bound to understand. We face the difficulty that human comprehension is limited when it comes to supernatural realities, but the game is worth the candle. One place to start is to remember that our current conception of angels as chubby infants floating in the clouds is a gross reduction of their scriptural manifestation as powerful beings waging war on our behalf.

Angelology is also a bridge to the mind of God. It tells us that our Creator God thought enough of us to provide us with their divine assistance, and that we would do well to turn to them. Angels can be understood as a midway point between God and man, sharing something with each. Comparing man with angels, then, “reveals what is distinctive about the Supreme Being believed to have created both.”

Angelology also provides knowledge that is necessary for understanding Scripture. For instance, to misunderstand the Archangel Gabriel is to fail to grasp the meaning of the events, like the Incarnation, in which he acts.

In my favorite section, Hurley explores the practical implications of the study of angels for our moral and spiritual lives. Angels teach us to be attentive to creation, looking without distraction at the inner form of things. Hurley suggests an “Angelic Pause” — a 60-second contemplation of some ordinary thing, like a leaf, to see it as an angel does, as it exists in God.

The angels who chose obedience so decisively are models of resistance to temptation. Our guardian angels, we learn, assist us by giving us clarity in moral dilemmas, consoling us in our distress, and nudging us providentially each day, if we are open to them.

There is also, of course, the angel at our death bed who is our last teacher. Hurley gives us a lovely Memento Mori prayer of his own composition: “Angel of my ending, teach me now what I must learn then: that all is gift, all is grace, all is God.”

With his book, you can put away modernity’s insistence that angels are only symbols that tell us about human needs. Instead, we can rely confidently on the help of these unembodied beings that mediate between us and God, fight the powers of darkness on our behalf, and tenderly watch over our children as they sleep.