Séraphine Louis, better known as Séraphine de Senlis (1864-1942), a French “outsider artist,” worked as a convent maid before her work was discovered, and by many accounts died in an insane asylum.

Séraphine was born to a peasant family in the village of Arsy in northern France. She was orphaned by the age of 6. Her eldest sister cared for her during one period. She supported herself for a time as a shepherdess.

By 1881, when she was 17, she was engaged as a domestic worker at the Sisters of Providence convent in Clermont, Oise.

From 1901 on, she worked as a charwoman for middle-class families in the nearby town of Senlis.

In 1912, German art collector Wilhelm Uhde was visiting Senlis when he chanced to see a still life of apples at the home of his host and learned that the artist was the man’s housecleaner, Séraphine.

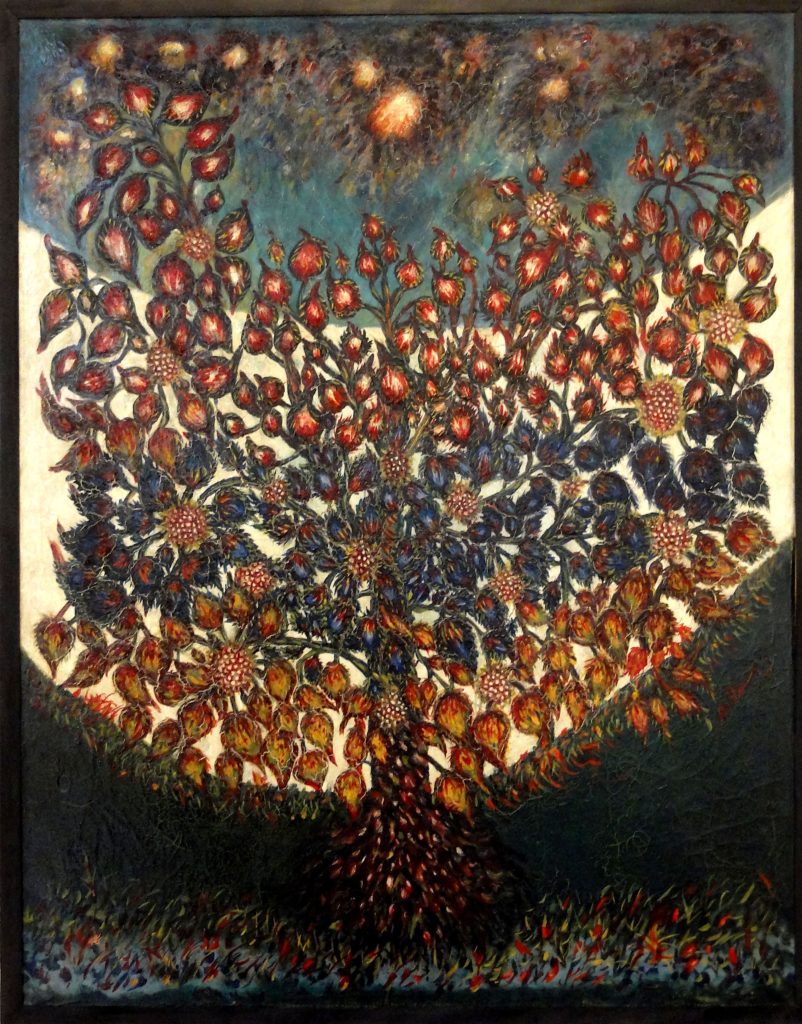

There were many more such paintings, Uhde was astonished to discover, of exuberant flowers, fruits and trees: “The Lord’s Garden,” Séraphine summed up this celestial heaven.

A fervent Catholic, she was inspired by the fields and woods through which she had loved to walk since childhood. She made her own paints from a secret recipe that may have included oil from the tapers burned in church, moss, clay, and blood. She worked by candlelight, with an image of the Blessed Virgin Mary gazing down upon her.

Uhde, an early collector of Cubist works, was also a champion of such well-known painters as Rousseau, Picasso, and Braque. Of Séraphine, he observed: “An extraordinary passion, a sacred fervor, a medieval ardor.”

“What can I tell you, sir?” she remarked to Uhde. “I paint as I pray. There’s no difference. I always say that I do all this for the Virgin Mary. I paint above all at night when the town is asleep. My still lifes are like gifts for the Good Lord and the Holy Mother. Necklaces of pearls and precious stones that I thread so they’ll be pleased with me. So I’ll go to Paradise.”

Uhde supplied Séraphine with painting materials, encouraged and supported her in every way, and saw to it that she was included among the “naïve artists,” as such unschooled painters were called, who flourished between the two World Wars.

Uhde was forced to flee France at the outbreak of World War I. When he returned in 1927, he assumed Séraphine had died, and was amazed instead to find her work featured in a local exhibit.

He also proceeded to collect many of her paintings and was responsible for launching a 1929 exhibit called “Painters of the Sacred Heart.”

Always an eccentric, however, Séraphine had become ever more prone to visions and states of near-ecstasy. Poverty and ill-treatment she could deal with. It was perhaps even a small measure of success that sent her over the edge.

Observed art historian Edith Hoffman in 1964: “Some of her flowers look as if they belonged to the flesh-consuming kind. Flame-like or hairy and prickly, they cover her canvases like growths that cannot be stopped, and malicious eyes are hidden among the leaves. The colours are often murky, and sometimes there is no composition but uncontrolled accumulation. Among flower-pieces these paintings are unique, for they express fierceness rather than a lyrical temperament. Undoubtedly Séraphine had reached the borderline of insanity when she painted them.”

Others saw, and continue to see, very different qualities. Wrote a blogger named Messy Nessy in a 2023 post:

“Séraphine’s paintings are characterized by a strong use of blues, greens, and violets, and she often used a limited palette of complementary colors to create a sense of harmony and movement in her compositions. She also used thick impasto, which is a technique of building up the paint on the canvas to create a sense of depth and texture in her paintings. Her thick impasto gave her paintings a distinctive, sculptural quality and added to the sense of movement in her compositions. Her technique was also unusual in that she would use both oil and watercolors in her paintings. … This combination created beautiful and lively effects in her paintings, and helped to give them a sense of movement and spontaneity.”

In 1932, Séraphine was admitted to the lunatic asylum at Clermont. The diagnosis was chronic psychosis. By all accounts, she never painted again.

The date of her death is disputed. Uhde maintained that she ended her days at the Clermont asylum in 1934. Others say she breathed her last on Dec. 11, 1942, in a Villers-sous-Erquery hospital in northern France.

What’s undisputed is that she died penniless and alone, and was buried in a common grave.

“Séraphine,” a 2008 French-Belgian biopic directed by Martin Provost, won the 2009 César Award for Best Film.

Her paintings are today exhibited in the Musée d’art de Senlis, the Musée d’art naïf in Nice, and the Musée d’Art moderne Lille Métropole in Villeneuve-d’Ascq.

And in Paradise at last, may she sit at the Virgin’s knee: still singing the praises of creation, still painting her numinous and mysterious flowers.