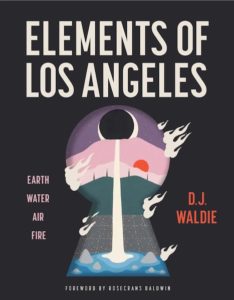

“Elements of Los Angeles: Earth, Water, Air, Fire” (Angel City Press, $30) is LA historian, memoirist, and lifelong Lakewood resident D.J. Waldie’s most recent book.

Using the four classic elements as his structure, Waldie seems to have read everything, talked to everyone, and traveled to every corner of the city that alternately mystifies, frustrates, delights, and alarms us. And that in the end we come back to, defeated by its sheer incomprehensibility, its eternal embrace, much as the lost-sheep disciples asked Jesus, “To whom else would we go?”

Waldie reaches high into the ether, miles beneath the surface of the earth, and deep into the past. Not just back to the original El Aliso, for example, the sycamore tree that grew in a place of sacred worship for the Kizh, the original inhabitants of the area, but back to the first “tufted seed” that, “in a year before years were numbered,” settled into a gash in the drying soil, and germinated.

After standing for more than 400 years, the tree was felled in 1895 for urban development and is now commemorated by a bronze plaque bearing the relief of a sycamore set into the sidewalk at the corner of Vignes and Commercial Streets in downtown LA.

We learn that the movie industry started not in Hollywood, but rather in Long Beach; the development by a mailman of the Hass avocado; of places and people that have more or less disappeared: the Japanese-American fishing community, for example, that flourished on Terminal Island from 1906 until the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Waldie covers the snake oil salesmen who, in a brief but disastrous craze, pushed radium as a health cure; the faith healers whose profit-generating messages reached hundreds of thousands over the radio airwaves; the Depression-era stunt people who, for a fee, allowed themselves to be buried in a glass-topped “casket” for months at a time while gawkers took photographs.

Smog, neon, the citrus business: his curiosity and erudition range wide.

We learn of massive disasters that today are all but forgotten. The 1863 explosion on the passenger-and-cargo steamship “Ada Hancock” off San Pedro Bay, for example, that resulted in 26 deaths. The 1928 catastrophic failure of the St. Francis Dam in Northern LA County’s Francisquito Canyon: at least 431 people perished in the ensuing flood. The Vineyard Junction wreck of 1913, in which two cars on the Venice Short Line Railroad, a high-speed trolley, collided, leaving 14 dead and 200 more maimed or injured.

No one ever seems to be held responsible, nor to hold themselves responsible, for these disasters. “[M]emory in Los Angeles is a labyrinth where overlapping narratives and counter-narratives converge, contradict, and frustrate,” observes Waldie.

He finished the book in the aftermath of the January 2025 Palisades and Eaton fires, and his grief and concern are palpable. How will we recover? Or perhaps more accurately, will we recover?

The book doesn’t claim to be exhaustive — how could it be? — and therein lies one facet of its beauty. Waldie led me to contemplate, among other things, the systems and grids and silent armies of dedicated people who we seldom see and who, day by day, keep our sewers, our power lines, our 9,000 streets, in good working order. The book led me to ponder my own map and memories of LA: the dark nights of the soul, the epiphanies.

Waldie doesn’t talk much about interpersonal connections: How we individually find our way in the labyrinth of Los Angeles — our rituals, our connections, our secret spots and private sanctuaries — would be another book.

Still, the two images that stuck with me are of two people: separately making their way; separately inhabiting both the shadows and the benediction of the famous LA light.

One is Waldie himself, who allows us a glimpse of him as he sits beneath the sycamores in front of the Lakewood conference center, reading. His eyesight is failing: next year he may have to resort to the enlarged type of a Kindle. We get the impression he’s sat in that same “wholly artificial” plaza countless hours over the years (he worked for decades at nearby City Hall), watching the street life, pondering, letting his essays and books ferment as he seeks, as he has most of his life, “to frame a sense of place for ordinary Angelenos.”

The other is artist David Hockney, a UK native who divides his time roughly between London and LA. For a time, Hockney would leave his home on PCH toward dusk and, with the top down on his candy-apple-red Mercedes 350SL, drive high into the hills above Malibu, blasting Wagner’s “Twilight of the Gods” (he’s hard of hearing) full volume.

Hey, the noise might “startle the tourists,” but who cares? As for his neighbors, they’re rich, too: If they don’t approve, they accommodate.

Partly, you think (along with the rest of the world), “Typical entitled Angeleno.” Partly, if you live or ever have lived in LA, you also secretly smile in celebration.

Motor up into those hills yourself and consider the glory of the earth, water, air, and fire that formed them. Smell the sage, feel the breeze, let your eyes range over those tawny, sun-dappled hills, look out over the sparkling Pacific Ocean.

If you had a candy-apple-red Benz, you’d probably put down the top and blast the speakers, too.

As Waldie says, “Every drive in Los Angeles ought to have a soundtrack.”