I knew exactly where I was on Sunday, Feb. 9, 1964. I was sitting on our living room floor staring at an old black-and-white television set. Why we called the TV a “set” I will never know. But on that Sunday night in February, we waited in great anticipation for “The Ed Sullivan Show.” The Beatles were going to be on, and our dad, who at the time had impressionable teenage daughters as well as impressionable younger boys like me, had decided he was going to use reverse psychology on us.

Instead of digging in his heels (as he would later) and prohibiting us from watching, he thought playing it cool and letting us see just how reprehensible and awful The Beatles were would stamp out the international conspiracy known as Beatlemania, at least the form it took in Van Nuys in 1964. Unfortunately for our dad, the minute Ed Sullivan declared “THE BEATLES” we were hooked.

To put the impact “The Ed Sullivan Show” had on American culture into perspective, think of the recently canceled “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert.” The latest Nielsen ratings for this No. 1 late-night talk show on network television was 2.5 million viewers. When Elvis made his debut on Ed Sullivan, 60 million people were watching. When The Beatles first appeared, 73 million watched.

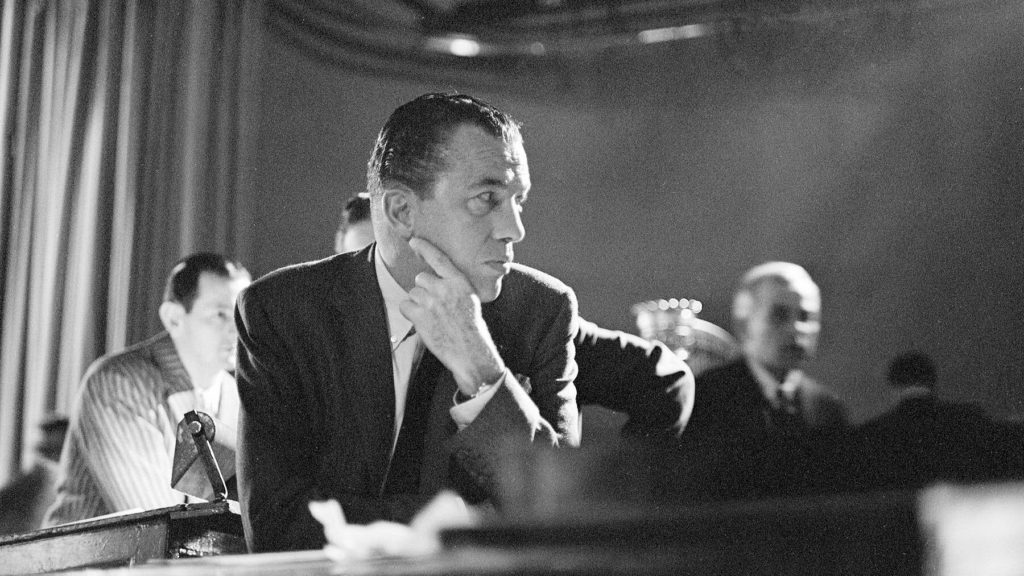

Netflix does a lot of bad stuff, but whether by accident or design, they also produce some excellent TV. This little bit of pop culture/television history known as the documentary “Sunday Best” may earn Netflix some time off purgatory for all their other sins. The life and career of Ed Sullivan, a true television pioneer, is worth watching for a variety of reasons. Sullivan grew up Irish, Catholic, and poor on the streets of Harlem when that part of New York was “reserved” for the Irish and the Jews. The documentary utilizes voice reenactments, but the words come directly from Sullivan himself. And the words are powerful.

His life and ethics were heavily influenced by his father. This alone was refreshing as usually poor, urban dwelling immigrant fathers trying to survive in America’s biggest city did not have great track records. Not so for Sullivan’s dad, who, although poor, maintained a dignity and commitment to decency he passed along to his son. His father and his faith imbued him with an intimate connection as to how it felt to be cast aside and thought inferior just because of your ancestry.

By the time Sullivan had made a name for himself as a sportswriter and Broadway columnist, Harlem had changed and was a bastion of African American culture and art — especially live entertainment.

Yes, Sullivan helped make Elvis and The Beatles huge stars in America. During this era from the 1950s and into the 1970s, “making it onto Sullivan” almost guaranteed a robust career. It is impossible to impress upon people on their electronic devices streaming and TikToking away that back in the day everyone — and I mean almost everyone who owned a TV set — watched the Sullivan show every Sunday night.

And what they saw, thanks to Ed Sullivan’s decency and inherited sense of justice, was a literal parade of African American entertainers beamed straight into the living rooms of New York, Los Angeles, and even in Mobile and Richmond. He got flak for doing this. He even got death threats and major advertisers dropped their sponsorships because Sullivan refused to keep black performers off national television.

In one instance, Sullivan was pressured to cancel an upcoming appearance of African American singer Harry Belafonte. In the documentary, Belafonte recalls how he was summoned to Sullivan’s New York apartment to explain his political activism as it related to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. On the surface, it would appear Sullivan and Belafonte were polar opposites. But even though Sullivan was a “garden variety” American patriot with photos of J. Edgar Hoover on the wall of his home, he and Belafonte shared something deeper. After their meeting where, according to Belafonte, each man stated their positions without apology, Sullivan called Belafonte’s priest to get another measure of the man. In the end, Belafonte appeared on the show.

There are archival photos peppered in the documentary showing Sullivan at his home office. There are photos on his wall of famous and influential people. I noticed there was also a photo of Bishop Fulton Sheen. Another photo showed Sullivan at his daughter’s wedding, obviously in the vestibule of their parish church. It was like looking into a 1950s Catholic time capsule. As the documentary makes clear, Sullivan would have never considered himself a social justice warrior or civil rights activist. He was just being a decent man in the tradition of his father and within the tenets of his faith.