Sister Wendy Beckett (1930-2018), a contemplative nun and consecrated virgin, delighted audiences worldwide during the 1990s with her BBC documentaries on the history of art.

Born in Johannesburg, she moved as a child to Scotland; in 1946 she joined the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, a teaching order, and earned a degree in English Literature at Oxford.

She then returned to South Africa and in spite of her “constant longing to pray,” lived an active life of teaching from 1954 to 1970. When she began to have stress-induced heart trouble and epileptic seizures, she was given permission to return to England. There, in solitude and silence, she found her true vocation.

She stayed for decades on the property of the Carmelite Monastery in Quidenham, praying for seven hours a day. Though she never became a member of the order, she signed over all her earnings to them.

With permission from the Church, she began to study art history, mostly from books and postcards. She published her first book — “Contemporary Women Artists” (Universe Pub, $7) — in 1988.

She went on to host her own television shows — “Sister Wendy’s Odyssey” and “Sister Wendy’s Grand Tour” among them — insisting upon a clause in her contracts that allowed her to attend daily Mass while traveling.

Hands clasped in joy, face framed by a wimple, she could with equal élan propose that Dutch Golden Age painter Gerard ter Borch’s “The Paternal Admonition” (1654) is actually a brothel scene, or suggest thinking of abstract artist Mark Rothko’s rectangles of color as “religious paintings without religion.”

Art critics sniffed at her “naïve” commentary. “I’m not a critic. I am an appreciator,” she responded with a smile. “I think great art opens us not just to the truth as an artist sees it, but to our own truth. ... You’re being invited to enter into the reality of what it means to be human.”

That point of view permeates “The Art of Lent: A Painting a Day from Ash Wednesday to Easter” (IVP, $9.89), one of her 30 books.

Approximately 6 by 5 inches and a compact 98 pages, the little volume is a delight to hold: portable enough to keep in your prayer corner, take on a stroll, or open on a park bench. The cover is of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Tower of Babel” (1563), all ocher stone and turquoise sea, and the color plates for each day of Lent are vivid and clear.

For the four days from Ash Wednesday through Saturday, she considers repentance (Japanese painter Hokusai’s “The Great Wave,” 1831); forgiveness (“The Return of the Prodigal Son,” c. 1661-69, Rembrandt); humility (“Self-portrait with Dr. Arrieta,” 1820, Goya); and purification (“The Harvest is the End of the World and the Reapers are Angels,” 1989, Roger Wagner).

Her selections range similarly wide for weeks one through six of Lent, for which the themes are, respectively, silence, contemplation, peace, joy, confidence, and love.

She doesn’t talk much about the painting itself: process, technique, school. She talks about the feelings, emotions, and insights that the work evokes.

Her overarching point is that art can open a window or door onto the transcendent. The short commentaries invite silent reflection, not argument or noisy thought.

In Rogier van der Weyden’s “The Magdalen Reading,” c. 1445, Mary Magdalene sits pensively over a page of Scripture, her sumptuous parrot-green robe a symbol of new, ever-replenishing, inner life.

Rembrandt’s well-known “The Jewish Bride,” 1665-67, prompts Sister Wendy to reflect that both the husband and the wife “are surrendering freedom, but willingly so, thus facing the truth that we cannot have everything. If we love, we make a delimiting choice.”

Manet’s achingly gorgeous “White Lilac,” 1882-83, was painted the year before he died. The “singleness of being” of this vase of simple flowers “must have moved him and perhaps consoled him, amid the anxieties and anguishes of own pain-filled days.”

But she hardly confines herself to the medieval, the Renaissance, or the French Impressionists.

Of contemporary painter Yuko Shiraishi’s at-first-glance monotonous “Three Greys,” 1987, she observes: “Its beauty, like much else we see, reveals itself only in time.”

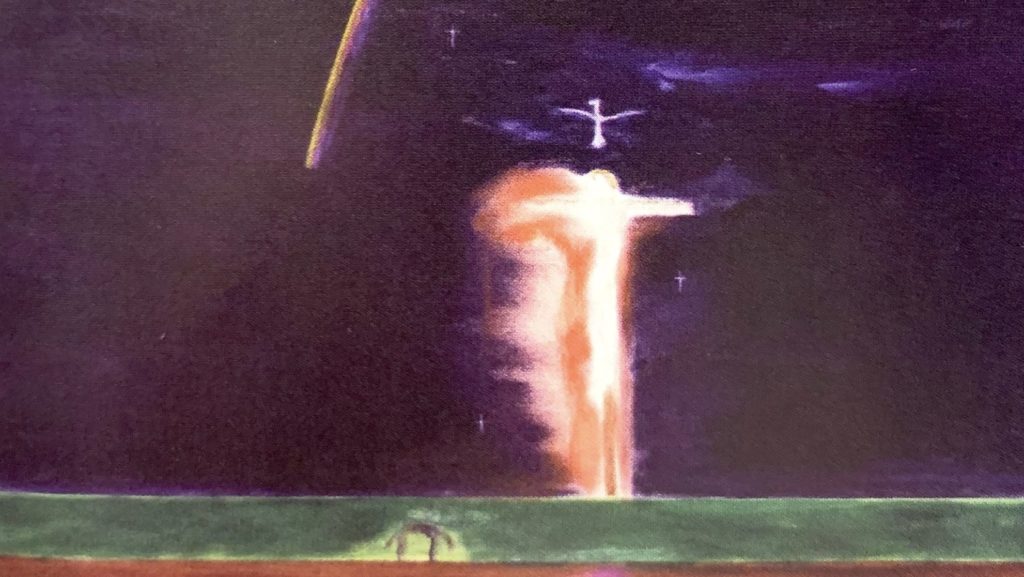

For Good Friday, she chooses “Crucifixion,” 2008, by Craigie Aitchison, in which Christ on the cross is depicted as “a luminous body blazing with the fire of love,” the Holy Ghost appears as “a skeletal outline,” and Aitchison’s beloved Bedlington Terrier gambols on “a strip of living green” below.

Aitchison is showing us, avers Wendy, “not what the crucifixion looked like, but what it truly meant.”

What the crucifixion truly meant is worthy of a lifetime of pondering, and a question we especially ask during Lent.

Wendy once wrote: “How do you know you are weak and unloving? Only because the strength and love of Jesus so press upon you that, like the sun shining from behind, you see the shadow. … Either we see all in the light of him, and primarily self, or we see only him and all else is dark. … But it is up to you to accept his grace; only you can thank him for it, and let it draw you, as it is meant, to long constantly and trustfully for his purifying love.”