I’ve developed a soft spot for those people we hear of from time to time who see Christ in a tortilla, Mary’s face in the trunk of a sycamore, the baby Jesus in the condensation of a hospital window.

In Protestant New England, where I come from, we had little regard for such phenomena. “Malarkey,” the grownups might have snickered, then doggedly continued chopping wood, hauling lobster traps, or canning peaches.

For many years after I converted, I harbored the same general view. So you had a vision — so what? Did it make you kinder, more forgiving, more patient? Have you become more Christ-like?

But over the years, I’ve had occasion to write about various visionaries, mystics, and stigmatists. And over the years, my view has softened.

Sister Mary Alfred Moes (1828-1899), for example, a Catholic nun of the Sisters of Saint Francis, saw a vision of a hospital rising out of a Rochester, Minnesota cornfield, and helped build St. Mary’s — the starter facility for what is today the world-renowned Mayo Clinic.

Snicker all you want, but who can deny that her vision bore rich fruit?

Servant of God Rhoda Wise (1888-1948), a Catholic laywoman, was a wife, mother, and convert from Canton, Ohio. Born to working-class, Protestant parents, Rhoda was the sixth of eight children. Anti-Catholic bias permeated the household.

At 16, Wise suffered a burst appendix. A nurse at the hospital gave her a St. Benedict medal which she kept ever after.

In 1917 she remarried widower George Wise. The couple adopted two daughters, one of whom died in infancy. George’s alcoholism was a source of ongoing poverty, shame, and embarrassment.

In 1932, Wise underwent surgery to remove a life-threatening, 39-pound ovarian cyst. In 1936, she tripped into a sewer drain and sustained serious injury to her leg.

During her convalescence, a Sister of Charity introduced Wise to St. Thérèse of Lisieux and taught her how to pray the rosary.

Wise was received into the Church in 1939, and continued to experience chronic pain and discomfort.

In the middle of the night on May 28, 1939, she woke to find the room filled with light and Jesus, garbed in a gold robe, sitting on a chair. A month later, she received a visit from St. Thérèse of Lisieux. Her abdominal wound, ruptured bowel, and leg were miraculously healed.

In the ensuing years, Our Lord and St. Thérèse appeared to Wise 20 more times.

From 1942 to 1945, Wise suffered the stigmata every first Friday from noon to 3 p.m. In her later years, she prayed for and helped heal a young woman who later became Mother Angelica and founded EWTN.

Today, visitors to the Rhoda Wise House and Grotto are promised: “Cures more wonderful than your own will take place on this spot.”

Many healings have been attributed to her. But maybe her biggest cure was this: Before she died, Wise’s alcoholic husband was relieved of the obsession to drink.

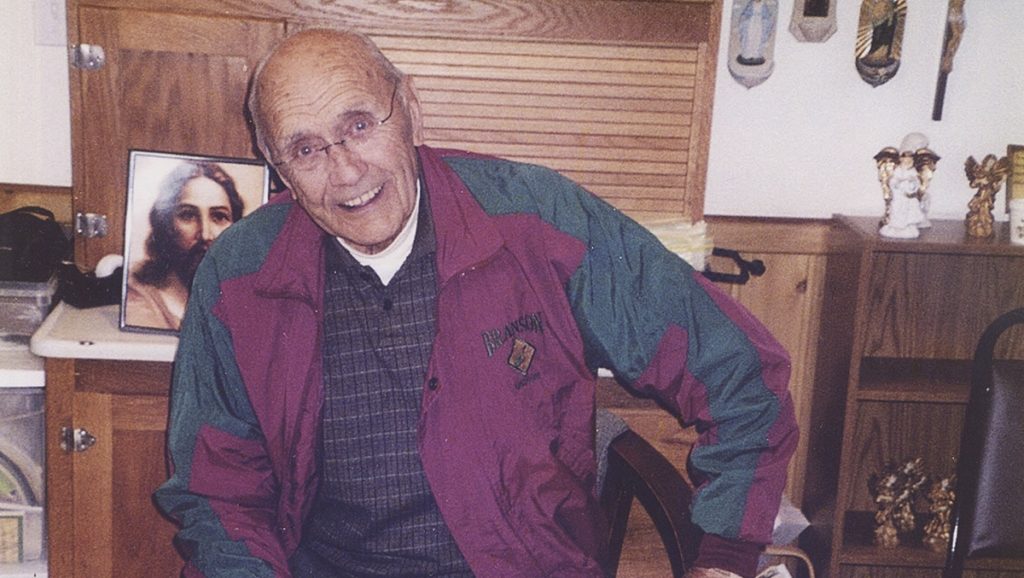

Servant Of God Irving “Francis” C. Houle (1925-2009), a Michigan husband, father, and “guy next door,” is said to have received the stigmata, and suffered the Passion every night between midnight and 3 a.m. until the day he died.

By all accounts a loving husband and father — he and his wife, Gail, would be married 60 years — Houle was a faithful communicant and prayed the Stations of the Cross every day after work.

Over the decades, Houle had jobs in retail and manufacturing. He became plant manager at Engineered Machine Products, where he was employed for the last 15 years of his working life. He was a bit of a prankster, a plain-spoken, solid family man with a penchant for jokes and teasing.

A 4th degree Knight in the Knights of Columbus, Houle received the stigmata on Good Friday 1993, at the age of 67. He was initially affected in the palms of his hands. “I’m taking away your hands and giving you mine — touch My children,” Christ allegedly told him.

Afterward, the physical suffering spread throughout his body. He was said to have suffered the Passion every night thereafter between midnight and 3 a.m.: those hours being “times of great sins of the flesh.”

Gail, luckily a sound sleeper, never witnessed these nocturnal sufferings, though others, including his brother Reynold, did. So did Father Robert J. Fox who, in 2005, published a book about Houle entitled “A Man Called Francis.” The pseudonym “Francis” was used in order to protect Houle’s identity, but the name stuck.

Houle avoided the limelight and neither sought nor accepted any financial donations for the myriad healings that were said to have flowed from his suffering and prayer. “Jesus is the one who heals,” he insisted.

He died at Marquette General Hospital, not far from the place where he was born: unassuming, unheralded, a sign of God’s strange and unexpected mercy.

The psalmist asked, “When will I come to the end of my pilgrimage and see the face of God?” And who am I to question that Christ comes to each of us how and in the ways he wishes?