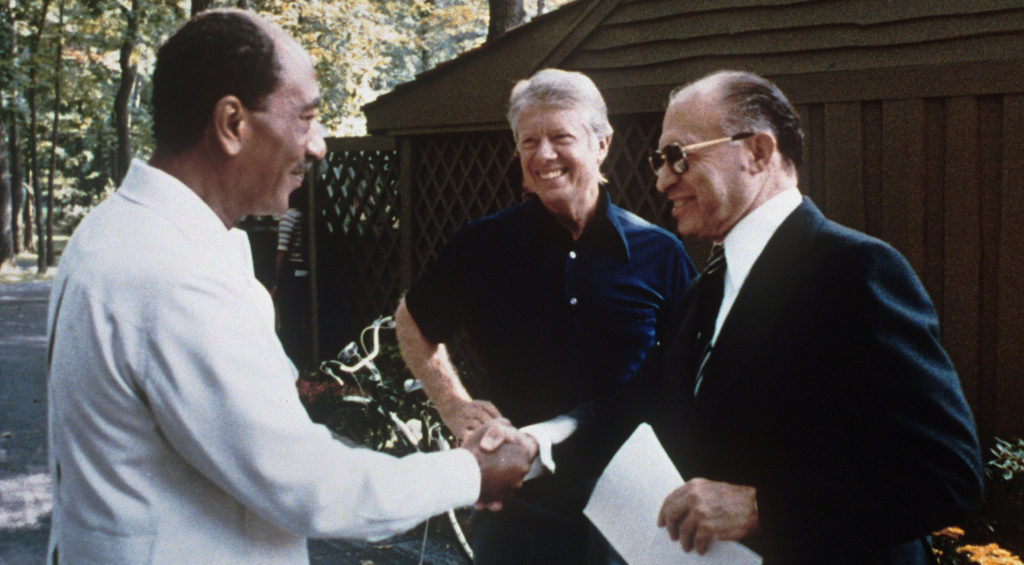

ROME — Amid the wave of tributes to President Jimmy Carter triggered by his death on Dec. 29, 2024, at the age of 100, much attention rightly focused on arguably his crowning achievement in the 1978 Camp David Accords, which led to peace between Egypt and Israel and the Nobel Prize for Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin.

Yet it was another, more fraught aspect of Carter’s foreign policy record that may loom larger today in terms of the complicated intersection among the White House, the Vatican, and the Middle East: the Iranian hostage crisis, which set the stage for a growing rupture and mistrust between Tehran and Washington, and which culminated in the famous “Axis of Evil” declaration under President George W. Bush.

A century ago, the idea that the United States and Iran would come to see each other as mortal enemies would have seemed counterintuitive. In the late 19th century, two Americans were actually appointed treasurers of the country by the Shah, a sign of Iran’s belief that the United States was a more trustworthy interlocutor than either the British or the Russians who were jockeying for control of Persia.

All that began to change with the CIA-backed 1953 Iranian coup, and it climaxed with the Iranian Revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Almost against his own instincts, Carter was forced by the hostage crisis into a position of hostility with Iran that has defined U.S. policy ever since, rising in intensity and volume level with every new American administration, Republican and Democrat alike.

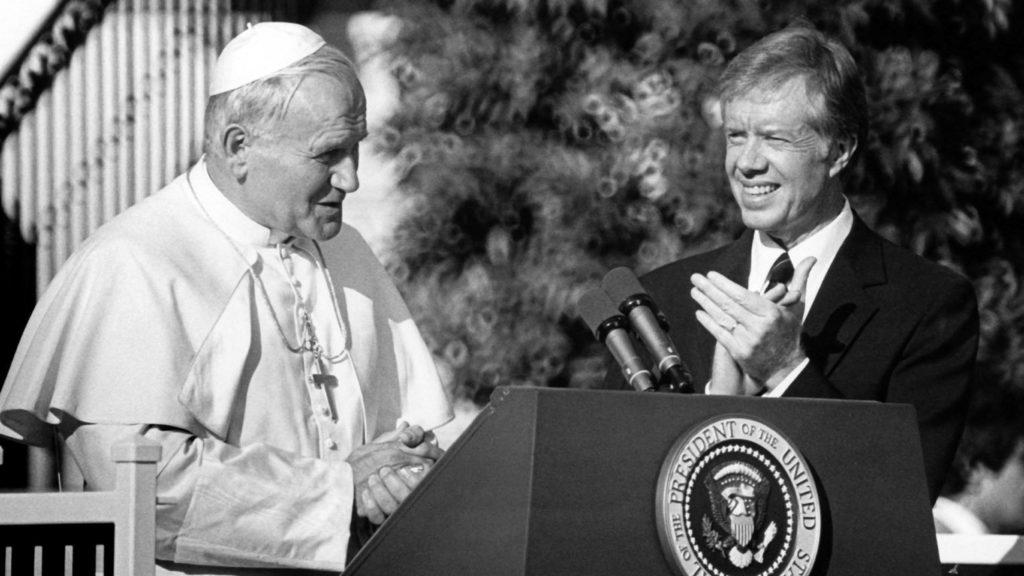

At around the same time as Carter and the Ayatollah were squaring off, a new pope was rising to prominence in Rome in the person of John Paul II, today known as St. John Paul.

(Fun Fact: Despite having served only one term, Carter is the only president in American history whose time in office overlapped with three popes: Paul VI, John Paul I, and John Paul II. Thirteen other presidents overlapped with two popes, beginning with John Adams and Popes Pius VI and Pius VII, and ending with Barack Obama with Popes Benedict XVI and Francis.)

Though the early phases of John Paul’s papacy would be dominated by the struggle against Soviet Communism — he developed an especially close bond with Carter’s National Security Adviser, fellow Pole Zbigniew Brzezinski, with whom he would discuss Soviet strategy in their native tongue — his geopolitical vision was hardly limited to Eastern Europe.

Among other insights, John Paul foresaw the rise of Islam as a globally relevant force, and he worked hard to position the Catholic Church as a friend. Speaking to a mixed group of Muslims and Christians during a trip to Casablanca in 1985, for example, he famously declared, “We have many things in common, as believers and as human beings. … We believe in the same God, the one God, the living God, the God who created the world and brings his creatures to their perfection.”

Later, in May 2001, John Paul would become the first pope to enter an Islamic place of worship when he visited the Grand Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, taking off his shoes in a sign of respect, and bowing in silent prayer before what Muslim tradition regards as the remains of St. John the Baptist.

Immediately after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, John Paul visited the mixed Muslim/Christian nation of Kazakhstan and prayed “with all my heart that the world may remain in peace.” He also called a summit of religious leaders in Assisi in January 2002 to urge peace, with Muslims the second largest group in attendance after Christians, including two representatives of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Unlike Western nations, the Vatican never broke off diplomatic relations with Iran after the revolution and the hostage crisis. In 1999, John Paul received Iranian President Mohammad Khatami at the Vatican. The two men spoke by phone just after the 9/11 attacks in an effort to keep the peace, and when John Paul died in 2005, Khatami travelled to Rome to attend the funeral. (The funeral occasioned a brief but friendly exchange between Khatami and then-Israeli President Moshe Katsav, leading some to joke that it was the deceased pope’s first posthumous miracle.)

All this leads us to today, and the looming onset of Trump II. After almost a half-century, the new U.S. leader faces a fundamental choice between the approach to Iran embedded in U.S. policy since the Carter administration, and the option of engagement embodied in the Vatican, whether that of John Paul or his successor in Pope Francis.

It may be difficult to imagine Trump as the Great Reconciler with Tehran, given that the Justice Department has charged Iran with plotting to assassinate the president-elect, and that Trump has vowed a “maximum pressure strategy” to bankrupt Iran as soon as he takes office.

And, yet.

Yet Trump may find an unexpected base of support among the Iranian population itself, which is increasingly chafing under theocratic rule. Media reports actually suggest many ordinary Iranians privately supported Trump’s reelection, on the grounds that they believed Kamala Harris was a vote for the status quo in U.S./Iranian relations, while Trump might be the one to force regime change.

Imagine this: If Trump is able to embolden an internal resistance movement to set the wheels of change in motion, Francis could play a vital role in reassuring Iran’s Islamic religious establishment that a change in government does not have to mean the end of the country’s religious identity, and that no matter what happens, they’ll have a friend in Rome, potentially ensuring that the transition is largely peaceful.

Should things shake out that way, a growing divide between American and Vatican approaches to Iran over the last half-century could reach a critical turning point in a surprising, even shocking, intersection between Trump’s “hard power” and Francis’ “soft power.”

Is that just a pipe dream? Maybe, but if you don’t believe the sudden collapse of an entrenched regime is at least possible, I’ve got some Syrians with whom you should have a chat.