For those who knew the strange story of Juan Gutierrez’s ankle, or even parts of it, the word “miracle” was hard not to think of.

A fluke basketball injury. Faulty medical advice. Unexpected inspirations during prayer. A sudden healing. The surprising involvement of the Vatican.

While the news of Gutierrez’s unexplained recovery from a torn Achilles tendon got out, it didn’t really get around, at least not far beyond where the story started: St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo, California, where Juan and other future priests for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and other Catholic dioceses in the western U.S. are trained.

The event was remarkable enough to be noticed by just enough people, while Gutierrez’s modest, shy demeanor seemed to divert any further attention from it.

But this odd combination of circumstances would eventually prove providential, confounding medical authorities, changing the life of this anonymous seminarian, and forever tying him to another young man who had been dead for almost 100 years: Pier Giorgio Frassati, who in August will be declared a saint of the Catholic Church on account of the miracle of Juan Gutierrez’s ankle.

• • •

This odd tale begins in Texcoco, a city on the peripheries of Mexico City, where Juan Manuel Gutierrez was born in 1986. His parents separated when he was 2, but at 19 he immigrated to the U.S. to join his father in Omaha.

It was there that, after being invited to a weekend retreat, he returned to the Catholic faith of his youth that he’d fallen away from. Soon, he found himself unable to shake the feeling that he was being called to the priesthood, and eventually wound up applying to enter the seminary in Los Angeles.

In 2013, he began college studies at the archdiocese’s Juan Diego House of Formation in Gardena. Graduating in 2017, he and his classmates moved to St. John’s Seminary to continue formation.

Every Monday, Gutierrez soon learned, St. John’s seminarians went to play basketball at a nearby gym in Camarillo. While not exactly an athlete, he’d always enjoyed sports as a youth, especially basketball and soccer, and the chance to compete again was a perk of seminary life for Gutierrez.

On Sept. 25, 2017, Gutierrez stepped onto the court: “I didn’t really warm up” that day, he remembered.

A few minutes into the game, Gutierrez had a feeling like someone had bumped into his right ankle, followed by a sound: “Pop!”

“When I heard the pop, I turned around and nobody was there,” Gutierrez recalled. “Like, absolutely nobody.”

What he did notice was that he couldn’t walk normally anymore. He headed for the bench and got a ride back to St. John’s.

Gutierrez remembered thinking that the injury “wasn’t that bad.” But the pain he began to feel didn’t let him sleep much that night. For a few days, he pushed himself to go to class and follow the seminary prayer schedule. But when another seminarian decided to go to the hospital to get an injury looked at, Gutierrez realized he had better join him.

At the hospital, the X-ray didn’t show any broken bones. A doctor prescribed painkillers, telling Gutierrez he had most likely pulled a muscle.

Back at the seminary, one of Gutierrez’s classmates had noticed him limping: Rene Haarpaintner was a widower in his 50s who’d left his medical practice to enter the seminary. He was still a licensed chiropractor, and suggested that Gutierrez walk with crutches to allow the pulled muscle to heal.

“It was bad,” remembered Haarpaintner, who was ordained a priest in 2023, a year after Gutierrez. “It was swollen everywhere and I could not really palpate (touch) much of it because the swelling was so big, everything was blue.”

When Gutierrez’s pain worsened over the next few weeks, Haarpaintner gave Gutierrez some stretching exercises to try.

Gutierrez dutifully complied, even though the stretches proved painful — really painful.

As Gutierrez’s pain got worse, Haarpaintner guessed he had suffered ligament damage. But that would take an MRI to confirm and the earliest appointment available was Oct. 31, which was almost three weeks away at that point.

In the meantime, Haarpaintner suggested that Gutierrez stay off his foot completely. He got through the month with a borrowed air cast and a makeshift brace. On Halloween morning, he drove himself to the radiology lab for the MRI.

Hours later, as Gutierrez was opening the gate to the seminary, his phone rang. It was the doctor.

When he saw the caller ID, “I knew that something was really wrong,” Gutierrez said. “I didn’t even say hello to him. I just picked up and said, ‘It’s bad, huh?’ ”

He had guessed correctly: “You have a tear in your Achilles.”

The doctor told Gutierrez to make an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon, and that surgery would be his best option.

A sense of dread came over the seminarian. Surgery would mean a long, painful road to recovery. His schoolwork would no doubt suffer, and how was he going to pay for the procedure? He still hadn’t told his family in Nebraska or in Mexico about the injury.

Gutierrez spent that night in his room Googling “Achilles injuries.” The pictures of blood and stories of infections associated with tendon surgery only made him feel more anxious.

• • •

The next day, Nov. 1, was the day the Catholic Church celebrates “All Saints’ Day,” remembering all the holy men and women in heaven. After Mass in the seminary chapel, Gutierrez stayed behind. His heart was heavy from the latest news.

“I was there, I was praying, and then at the end, I was like, you know, I think I need help from above,” he recalled. “I was having this conversation with myself in my head.”

At some point, the thought entered: “Well, why don’t you make a novena?”

It wasn’t a strange idea. Growing up, Gutierrez had prayed plenty of the nine-day devotions to different saints. Novenas aren’t “magic,” he’d come to believe, but “a journey of faith and prayer.”

For Gutierrez, the question was: who do I pray to? Then the conversation did take an odd turn.

“I had this whisper in my head that tells me: ‘Why don’t you make it to Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati?’ I just remember thinking, ‘Oh yeah, that’s a good idea.’ ”

It was a peculiar thought, given that Gutierrez didn’t exactly have any personal devotion to Frassati. He’d been introduced to him in the same way he’d learned about so many other saints: watching YouTube videos.

Frassati had been born in Turin, Italy, in 1901 to Alfredo Frassati, a journalist (and later, a politician and diplomat) who founded the major Italian newspaper La Stampa, and Adelaide Ametis, a respected painter.

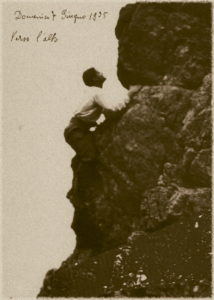

His father was an agnostic, but Frassati early on developed a deep devotion to the Eucharist, attending daily Mass and spending long hours of prayer in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament. An avid outdoorsman and mountain climber, he would eventually spend much of his own fortune to help the local poor.

He died in 1925, a few days after falling ill with polio, which he probably contracted while visiting sick people in a slum area of Turin. He was just 24 years old.

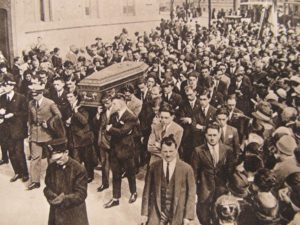

Hundreds of the city’s poor followed his coffin during his funeral procession, and within a few years a movement began to have him declared a saint. Frassati became associated with the phrase “verso l’alto” (meaning “to the heights” in Italian), which he wrote on a photograph of his last climb.

Among his admirers was St. Pope John Paul II.

John Paul, a skier, a hiker, and an outdoorsman himself, found a kindred spirit in the idealistic and energetic young Frassati.

He held him up often as a role model for how young Catholics can follow Jesus in a complicated and changing world.

“He was a modern youth,” the pope told a gathering of young people in 1983, “open to the problems of culture, sports, to social questions, to the true values of life, and at the same time a profoundly believing man, nourished by the Gospel message, deeply interested in serving his brothers and sisters, and consumed in an ardor of charity that drew him close to the poor and the sick. He lived the Gospel beatitudes.”

When Frassati’s remains were moved to the Cathedral of Turin in 1981, his body was found incorrupt, that is, showing none of the ordinary signs of decay after death.

In 1990, John Paul declared him “Blessed,” beatifying him after the Vatican recognized the healing of a man from tuberculosis who prayed to Frassati as a miracle attributed to his intercession.

And so it was on that fateful All Saints’ day in 2017 that Gutierrez came back to the chapel to start the novena to Blessed Frassati, praying it during the time set aside for seminarians to pray before the Blessed Sacrament.

At no point during the novena did he ask to be healed, he stressed.

“My prayer was, ‘Lord, through the intercession of Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati, I ask you to help me in my injury.’ ”

Gutierrez said he would have ended the prayer there, before praying the usual rosary to accompany the novena.

But at that moment on that first day, he had what he calls another “inspiration,” to follow up that prayer with a declaration: “…and I promise that, if anything unusual happens, I will report it to whomever I need to report it to.”

“That part did surprise me,” recalled Gutierrez. “I’m like, where did that come from?”

It would prove to be a thought worth holding. Because unusual things were about to happen.

• • •

A few days later, Gutierrez entered the chapel to pray his novena. It wasn’t during the usual 5 p.m. Holy Hour, he remembered, because nobody else was there this time.

He recalled feeling “a warmth around the area of my injury” as he knelt and was praying.

“It was gentle,” Gutierrez said. “But it would increase little by little, and at some point I thought that an outlet of the electrical was catching fire. And I was looking for the fire. And there was no fire there. So I just remember looking at my ankle and thinking, ‘That’s so strange’ because I could feel the warmth.”

Gutierrez knew from his past experiences with the Charismatic Renewal movement that heat is sometimes associated with God’s healing. Gutierrez looked up toward the tabernacle holding the Blessed Sacrament. He began to cry.

“I told the Lord in my heart, ‘It cannot be. Not because you don’t have the power to heal me, but because I know that I don’t have the faith for something like this.’ And that moved me.”

His tears having dried and his prayers finished, Gutierrez left the chapel. He doesn’t remember exactly what day the mysterious experience took place, only that there were a few days left before Nov. 9, when his novena was set to conclude.

He does remember that after that day, he stopped wearing the brace used to keep his right foot immobilized: “I just didn’t need it anymore.”

Gutierrez had an appointment scheduled for Nov. 15 with an orthopedic surgeon. At some point, he realized that he was not even thinking about his injury anymore.

• • •

On Nov. 15, inside his downtown LA office, the orthopedic surgeon asked his new patient what he did for a living.

“I’m a seminarian, which means I’m studying to be a priest,” Gutierrez explained.

To confirm the diagnosis of a torn Achilles indicated by the MRI images, the surgeon conducted something called the Thompson test, which involved squeezing the patient’s calf as he laid face-down on the hospital bed. If the foot moved when he squeezed, that would mean the tendon was connected. If it didn’t, it would confirm the tear.

“Hmm,” Gutierrez heard the surgeon mutter after squeezing. Then the surgeon pressed his thumb on the place where the MRI showed the tear.

“Does it hurt?” he asked.

Gutierrez felt a slight sensation of muscle soreness, but no pain. The doctor asked if he could press harder, and then harder again. Still Gutierrez felt no pain.

Sitting back up, he noticed a puzzled look on the surgeon’s face. Pressing directly on the area of the tear, he’d expected to feel the gap with his thumb, something Gutierrez had felt the couple of times he had dared to examine his ankle.

“You have no gap,” the surgeon said. “You must have somebody up there looking after you.”

A chill went down Gutierrez’s spine. He remembered the novena. Then he began to pepper the doctor with questions.

Could the gap have closed on its own? No, the doctor replied, in fact, they tend to open even more over time. What if the MRI was wrong? No way. “This is the most advanced piece of technology we have for something like this.”

Pointing to the screen, the surgeon told the seminarian, “As of Oct. 31, you had a tear in your Achilles, but now I can’t find it.”

• • •

At the time, Gutierrez wanted to tell everybody about this strange development. But he was afraid of drawing too much attention to himself. He resolved to only tell a few of those close to him.

At St. John’s, his fellow students noticed that he was no longer limping and no longer wearing the brace. When they asked him about it, he kept his answers simple, saying only that a doctor had told him he didn’t need surgery after all. The fact that he hadn’t made a big deal about his injury in the first place helped tamp down on further questions

“Juan’s a pretty low-key guy,” said Father Tommy Green, a classmate of Gutierrez’s who was ordained a priest in 2024. “It kind of just fell off the radar.”

Within a few weeks, Gutierrez was jogging, and ready to move on with seminary studies and normal life. He only confided about the healing to his spiritual director and a few close friends. As far as he was concerned, the story was over.

Then he got a reminder about the second part of his novena prayer.

Gutierrez was wandering the exhibit hall at a youth conference a few months later when he came across a booth featuring a life-size photo cutout of Frassati. The booth was unattended. Taking some Frassati prayer cards, he noticed on the back an email address where people could send stories of favors they had received through Frassati’s intercession.

He remembered his promise: “If anything unusual happens, I will report it to whomever I need to report it to.”

He put it off for a few months, but eventually sat down to type his testimony and email it.

“To me, that day was the end of it: I fulfilled my promise to Pier Giorgio that I would report it,” recalled Gutierrez.

He never received a reply to his email. Once again, he thought the story was over.

Two years passed, it was now the fall of 2020, and he found himself sitting at St. John’s in a class being taught by Msgr. Robert Sarno, an American priest who had recently retired after nearly 40 years at the Vatican’s Dicastery of the Causes of the Saints.

The subject of the course? The diocesan phase of canonization causes.

“I was like, ‘Oh snap,’ maybe there’s something here that will make me tell my testimony about my experience with Pier Giorgio to somebody, ” Gutierrez thought.

When the class turned to the subject of how the Church investigates claims of miraculous healings, the thought of approaching Msgr. Sarno with his story only made Gutierrez more nervous. He could picture the straight-talking Brooklyn priest brusquely dismissing his tale as a “nice story.”

“Jesus, give me courage to say something about this because I personally don’t want to,” Gutierrez prayed.

• • •

One day after breakfast, Gutierrez worked up the courage to approach Msgr. Sarno and tell him his story.

Msgr. Sarno looked at him and asked, “Why did you wait this long to tell me this story?’

“Because you’re very intimidating,” the seminarian replied.

“Yeah, I’ve been told that before” Msgr. Sarno said.

At dinnertime the same day, Msgr. Sarno approached Gutierrez to tell him that Rome was “very interested” in his story.

In an interview with Angelus, Msgr. Sarno said, “It was the last thing that I had expected, that in this course that I was teaching in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, there could be a potential miracle for the canonization of Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati.”

After talking to Dr. Silvia Correale, J.C.D., the Argentine-born lawyer who was heading up Frassati’s canonization cause in Rome, Msgr. Sarno suggested to Gutierrez that it would be “prudent” not to speak about his experience to anyone else.

The reason was that Msgr. Sarno had been given the “green light” to initiate a diocesan-level canonical investigation into Gutierrez’s case. Msgr. Sarno worked on the sainthood causes of such legendary figures as Sts. Mother Teresa of Calcutta and Damien of Molokai, among others.

Explaining the caution he gave to Gutierrez, Msgr. Sarno told Angelus: “You don’t want to prejudice the witnesses of a potential investigation. You want to keep all the witnesses completely free to be examined without any restrictions or coloring or, bias, if you will, in the case.”

From there, the process began to move. Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez authorized Msgr. Sarno to head up the archdiocese’s investigation of Gutierrez’s story.

Two LA priests, Father Joseph Fox, OP and Msgr. Michael Carcerano, were appointed to help with the judicial process, and in the fall of 2023, Msgr. Sarno returned to St. John’s to interview witnesses and gather evidence, including doctor’s notes, the initial MRI scan, and other documents.

Among the seminarians interviewed was the chiropractor, Haarpaintner.

Because the doctors who examined Gutierrez at the hospital had missed that it was a torn tendon, Haarpaintner testified, it is likely that his recommended stretching exercises had actually made that tear worse. This, he believed, made a sudden recovery even more improbable from a medical standpoint.

Haarpaintner said it was a lesson in humility when he was also asked to speak over Zoom to a Vatican medical panel investigating the possible miracle.

He said a surgeon on the call told him, “You screwed up, you aggravated the injury by putting his foot in plantar flexion.”

“Yes, I did, sorry, I did!” Haarpaintner remembered answering.

“Can you imagine what that was like for my vanity? Not good,” joked Haarpaintner, whose hometown in Switzerland is a few hours’ drive from Blessed Frassati’s native Turin.

“This is the best case of malpractice in the eyes of God, that's for sure.”

By the time Sarno submitted his findings to the Dicastery for the Causes of the Saints, he felt confident that he had stumbled upon the miracle that everyone was waiting for in the case.

“I believe in Divine Providence,” Msgr. Sarno said, “And there are just too many accidents in this case.”

On Nov. 20, the Vatican announced that Frassati would be canonized next Aug. 3 during the 2025 Jubilee Year celebration for young people, following the canonization of Blessed Carlo Acutis, another Italian youth known for his deep love for the Eucharist and the poor. Five days later, Pope Francis formally approved the second miracle attributed to Frassati’s intercession.

While the canonization of Acutis was widely expected for next year’s jubilee, the Frassati news came as “a great and happy surprise” to those familiar with his cause, including Msgr. Sarno.

“The fact that Pier Giorgio’s canonization will happen during the 100th anniversary of his death, plus during the holy year of 2025, plus the fact that Carlo Acutis will be canonized during the jubilee weekend for teenagers, Pier Giorgio during the one for young adults … you can’t say that that’s not Divine Providence either,” said Msgr. Sarno.

• • •

With the strange story of Gutierrez’s ankle now officially recognized as a miracle and the secrecy surrounding his healing gone, the 38-year-old priest is ready to introduce his saintly friend to new generations.

Since his ordination in 2022, Father Gutierrez has served as associate pastor at St. John the Baptist Church, a suburb east of Los Angeles. In another curious coincidence, the cathedral where Frassati is entombed is also named for St. John the Baptist. The parish has a heavy Hispanic and Filipino presence, with multiple ministries for young people and at least a dozen Masses every weekend.

“I think Pier Giorgio was a great role model for what it is to be a young Catholic in the world,” said Gutierrez. “Someone who takes ownership of our Catholic identity, someone who is involved in the lived experience of the faith, not only in the walls of your church, but even beyond that.”

The experience has shown Gutierrez that when it comes to heavenly intercession, “we don’t choose the saints, the saints choose us.”

So why did Frassati choose him, of all people? The priest hasn’t really figured it out, since he certainly doesn’t share the Italian’s wealthy background, or his athleticism. “To this day, I’m still trying to receive the miracle of becoming a hiker,” he jokes.

That said, Gutierrez sees at least one clear connection that might explain the workings of Providence.

“He was known to have a heart for the needy and the poor,” said the priest. “Maybe it wasn’t a big deal at the moment, but in my time of need, he drew near to me and he helped me. And there are a lot of people who have received graces from him. I’m not the only one.”