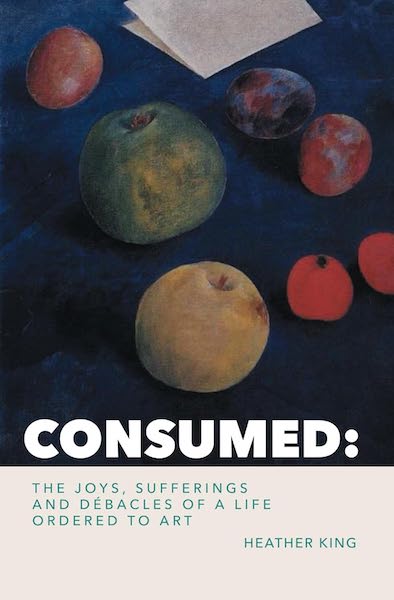

I have a new book out this month: “CONSUMED: The Joys, Sorrows, and Débacles of a Life Ordered to Art” (Holy Hell Books, $11.99).

It’s for the many people who have written to me over the years asking how to be a writer, how to start, how to get an agent, how to get published, and how to persevere. I’m not a teacher and, even if I were, I’m not sure writing can be taught. I have, however, been a self-supporting, working writer for 30 years. Part memoir, part guidebook, “CONSUMED” is an eccentric gathering of reflections that have emerged during that time on process, craft, vocation, and the avoidance of despair.

It also includes 30 essays on artists I admire, many of whom I’ve written about here.

Here’s an excerpt:

On a recent gray day, I settled down to one of my favorite kinds of afternoons: a new book, and a bedside table of snacks. Namely, I started reading “Heavy Light: A Journey through Madness, Mania & Healing” (Chatto & Windus, $13.82) by British writer Horatio Clare.

H, as his friends (and now, I) call him, wrote a stellar memoir about growing up on a Wales sheep farm called Running for the Hills, and has written several travel and landscape-type books since.

He’s also possibly an alcoholic, and possibly bipolar, and suffers from Seasonal Affective Disorder, and really, really should not smoke pot.

He’s covered some of that in his previous books but this one is about a flat-out, rather flamboyant breakdown in which he took off all his clothes, for example, and rolled his car off a cliff.

He was “sectioned,” as they call it in England (we would say carted off to the psych ward). And I haven’t finished the book yet but I gather it’s about how we could possibly start thinking about and treating mental illness in ways that do not primarily involve prescribing incredibly strong drugs with severe, often irreversible, side effects.

Even the doctors don’t understand how most of them work. And the patients, of course, are caught in a catch-22 such that they can only be released from the nuthouse if they agree to take the horrible drugs. Not that the drugs don’t sometimes help, BUT.

Clare meanwhile has a long-term partner, Rebecca, a more or less stepson, 17, and another son with Rebecca, 6. Who are all deeply frightened, pissed, anxious, hopeful, loving, frightened, etc.

So the book is a great read, but even better, because Clare writes, reads, listens, travels, and mingles, it’s the kind of book that had me reaching for my phone every five or 10 pages to explore. I learned, for example, that a coracle is (especially in Wales and Ireland) a small round boat made of wickerwork covered with a watertight material, propelled with a paddle, and that is shaped like half a walnut shell.

That cheered me to no end! I learned about sculptor Barbara Hepworth and about the Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden (which H could walk to from “the facility” once he was allowed day passes). I learned about Bardsey Island (the island of 20,000 saints) in Wales, and I learned that you can stay there in a white-washed cottage with a stone wall and a red door and basically nothing around but a restaurant and the birds.

I learned of the painter Brenda Chamberlain who lived on Bardsey in splendid isolation for many years, then moved to Greece, then moved back and died of a barbiturate OD (memoir-novel “Tide-Race” (Seren, $21.93) on order).

I learned of the Dylan Thomas poem, “In My Craft or Sullen Art.” I learned that H had visited an isolated former parish (and felt right at home) of Welsh poet R.S. Thomas, whose biography “The Man Who Went Into the West” (Aurum Press Ltd., $15.70), by Byron Rogers, I promptly ordered. I looked up the word “mordant” for about the 10th time in my life, and hope to use it in a sentence one day.

I learned that Clare walked the same 250 miles to Lübeck, Germany, that Bach walked in 1705 and wrote a book about that. (Which you can also listen to).

Through some other similar, recent follow-the-breadcrumbs trail, I have also happened upon the mostly unknown British painter Theodore Major (1908-1999).

Major shunned publicity, mostly refused to sell his paintings, lived in voluntary poverty, and adored children, beauty, truth, his wife, the gritty town of Wigan, and the hard-working, hard-scrabble, noble-in-spirit people of the County of Lancashire (people who were thought unworthy of notice or admiration by most of the rest of the world, especially the art world). He was a recluse, a bit off-kilter perhaps. In short, my kind of guy.

The point being that if you stray even a bit off the beaten path, you come upon all kinds of fascinating people out there who forged, or are forging, their own little path.

And who thereby provide some light to live by.