For Americans this year, June 19 is now a national holiday celebrating Juneteenth, the symbolic anniversary of the elimination of slavery in our country.

But also this year, the date marked the 400th anniversary of the death of Blaise Pascal, a French thinker of extraordinary genius — including in science and mathematics — as well as a writer who played an important role in the imagination of Western culture. Because of his contribution to Christian thought, Pascal has been celebrated for centuries in many different countries, including by non-Catholic Christians and even nonbelievers.

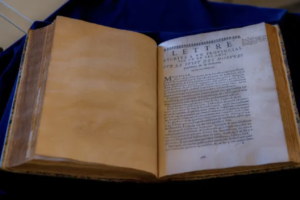

Pope Francis signaled the Church’s debt to Pascal this year by publishing an apostolic letter, “Sublimitas et Miseria Hominis” (“The Grandeur and Misery of Man”), and it is a beautiful tribute to the great thinker and great Christian. The letter should be seen as part of the Church’s effort to evangelize the culture of our time, in this case the high culture of intellectual achievement.

The title of the document is a brilliant capsule summary of Pascal’s understanding of the paradoxes of the human condition. The Frenchman was above all a dialectical thinker, not only noticing the contradictions (which he called “disproportions”) in our nature but also embracing them and seeing their reconciliation in Jesus Christ.

Francis quotes a typical paradox from Pascal’s book (posthumously edited) called “Pensées” (“Thoughts”): “What is man in nature? Nothing with respect to the infinite, yet everything with respect to nothing.”

Over and over again, in masterful metaphors, Pascal pointed out the contradictions of human existence. The human being is the best and the worst, both grand and miserable, exalted and lowly at the same time. The recurring motif of Pascal’s great wisdom is the dialectic between the infinite divine and the limited human.

In the letter, the pope sketches the life of the great thinker who died at the young age of 39. A child prodigy, educated by his widowed father who was a bureaucrat in the French government, Pascal achieved great acclaim in the field of mathematics. At 16, he wrote a brilliant paper on conic sections; by 19, he enjoyed worldwide renown among scientists.

He invented a machine considered a precursor of computers and produced papers that laid the foundation of calculus. His practical nature helped him to devise a plan for public transportation for Paris.

But this scientist had a mystical side that combined his scientific precision with what the theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar called “that quite other precision appropriate to the realm of being and to the Christian realm.”

Pascal saw grace in the chaos of contrasting aspects of existence. “Christianity is strange: it requires human beings to recognize that they are vile and even abominable, and requires them to want to be like God. Without such a counterweight this elevation would make them execrably vain, or this abasement execrably despicable.”

The dialectical human conflict is brought into harmony by God’s grace because “In Jesus Christ all contradictions are reconciled.” He proposes that there are only two types of people: “the righteous who think they are sinners, and the sinners who think they are righteous.” The paradox of grace is a remedy for the overwhelming self-centeredness to which we are prone. A person must both hate and love self, knowing he is capable of baseness but open to the infinite love of God.

The apostolic letter is an invitation to study and appreciate Pascal’s seesaw anthropology, the combination of opposites. He articulated a way to think about God’s greatness compared to human weakness, which landed him in controversy, because he saw threats to the recognition of the awesome majesty of God. This fear was the basis of Pascal’s conflict with many Jesuit writers of his time. He thought that many of his opponents discounted our absolute and abject need we have of grace, and had fallen into the heresy of the Pelagians.

His masterpiece, which the eloquent 17th-century French theologian Bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet said was the only book he wished he could have written, was “The Provincial Letters.” Published almost like the “samizdat” press, a system of clandestine printing and distribution of dissident or banned literature of the old Soviet bloc (both the king and the pope at the time wanted it banned), the book was all the rage in France. Some historians believe that it was partly responsible for the climate of opinion that led to the Jesuit order’s suppression a little more than 100 years later.

It is interesting — and ironic — that a Jesuit pope would single out the greatness of the Frenchman famous for his opposition to the order. The pope praises the polemicist’s “candor,” and summarizes the conflict as a study in the theology of grace and a part of the tremendous controversy surrounding 16th-century Jesuit theologian Luis de Molina’s proposed understanding of how man’s freedom and God’s omnipotence can be reconciled.

Pascal’s challenging proclamation of God’s tremendous transcendence was brilliantly described in the Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski’s book, “God Owes Us Nothing.” The obvious corollary of the book is that we owe God everything, a radically countercultural message for man who is, in Pascal’s description, “a monster, a chaos, a contradiction, a prodigy! Judge of all things, and imbecile norm of the earth, depository of truth, and sewer of error and doubt; the glory and refuse of the universe. Who shall unravel this confusion?”

Francis’ letter is a recognition that Pascal is, in many ways, a thinker for our time. His “Pensées” was a work of apologetics addressed in the Age of Reason to people who doubted the Gospel. We live in an age of doubt and indifference, and Pascal’s penetrating argument, based on his famous observation that “the heart has reasons, reason cannot know,” speaks to the intellectual confusion of our culture. May it reach our hearts. That would be another liberation to celebrate.