Stephen F. Auth serves as executive vice president and a chief investment officer of Federated Global Equities in Manhattan. He’s also a Catholic who, along with his wife Evelyn, has led the New York City street mission for more than 14 years.

Most to the point here, he’s a lover of art, intimately familiar with the world-class, world-renowned Metropolitan Museum.

He and Evelyn had been haunting the Met galleries for years when, on a guided tour in September 2009, the docent stopped in front of a small Rembrandt painting called “The Toilet of Bathsheba.”

The docent accurately contextualizes the painting in terms of art history and the trajectory of Rembrandt’s work. She points out the shadowy figure of David in the upper left corner. She reports that Bathsheba is one of the very few nudes painted by Rembrandt in the heavily Protestant Dutch Republic of the 1600s.

Auth notes: “Everything she says is delivered cleanly and precisely. It’s all entirely accurate. Objective. Neutral. Almost scientific. That fits well with my own prejudices. My classical training at one of the country’s great universities has left me instinctively of the mind that art can and should be studied in an almost scientific context.”

“Still, as the docent whisks the group forward to Rembrandt nearby self portraits, I find myself lagging behind, reflecting.

“Beneath the rich surface of this canvas, something is stirring. Something dark.”

Raised Catholic, Auth had fallen away from the faith over the years but at this point was slowly coming back. In spite of the religious content of much of the art — both at the Met and the many other museums he had visited in the course of his travels as a global financier — he had seldom actually connected the art to religion.

But the story of David and Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11-12:25), as you may know, includes seduction, adultery, betrayal, and murder. And standing in front of the Rembrandt masterpiece, a thunderbolt hit.

“ ‘The Toilet of Bathsheba’ was not about the nude Bathsheba…I was looking at the image of Bathsheba through David’s eyes as he stared out from the ramparts of his castle — what my priest friend always calls the dangerous ‘second look’…‘The Toilet of Bathsheba’ was Rembrandt’s take on David’s fall and redemption, or perhaps his own. Or, perhaps closer to the mark, my own.”

He realizes that he and Evelyn have been looking at art through the wrong lens. Art, all art, he sees, is about man’s search for God — and therefore, the individual viewer’s search for God.

He enlists the aid of a priest friend, Fr. Shawn Aaron. The three begin viewing art from a new perspective in which the works form “a story that rang true.” They began leading informal Met tours for whoever was interested.

“Pilgrimage to the Museum” (2022) takes the reader along, on a written and visual overview of art from the Egyptians through the contemporary era.

Auth’s lens, rather than art history or theory, is the seeking, hungering human soul. His commentary is conversational and gently opinionated, brought alive by relevant Scripture quotations and color plates of the major works discussed.

The ancient Egyptians asked the same existential questions we do: “What is the meaning of life?” “Where am I heading next?” “Who is God?” Their answer was basically, “I am God.” The tombs of the rich and powerful were peopled with images of servants and attendants bearing every possible material good into the next realm.

The Greeks, by contrast, saw God as men, depicting classically perfect bodies as, for example, in Polykleitos’ diadem-crowned athlete Diadoumenos, and Kallimachos’ marble statue of Aphrodite.

The Romans’ credo was “No God but me.” Belief in the Middle Ages was premised on the thought: “You are God; I am not.”

In the 1300s art pushed in a new direction, one based more on Earth than in the world of the spirit. Mary began to be depicted with inner thoughts. Human drama was added to scenes of the Annunciation, the Last Supper, the Crucifixion.

Auth takes us through the High Renaissance (“Creation Through the Eyes of the Creator”), “The Spiritual Synthesis of El Greco, Mannerism, and Spiritual Rebirth,” and “The Battle of Light and Darkness” exemplified in art of the Baroque through the Rococo.

Thus we’re well prepared for “The End of the Soul and the Death of God.” Auth finds much to like in Realism, Impressionism, and modern art. He gives a fair read to Picasso, Seurat, Edward Hopper, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock. He celebrates Salvador Dali’s 1954 “Crucifixion,” which depicts an ascendant, cosmic Christ.

But he’s also clear that the soul searching for God finds little sustenance in art grounded in atheism and secularism.

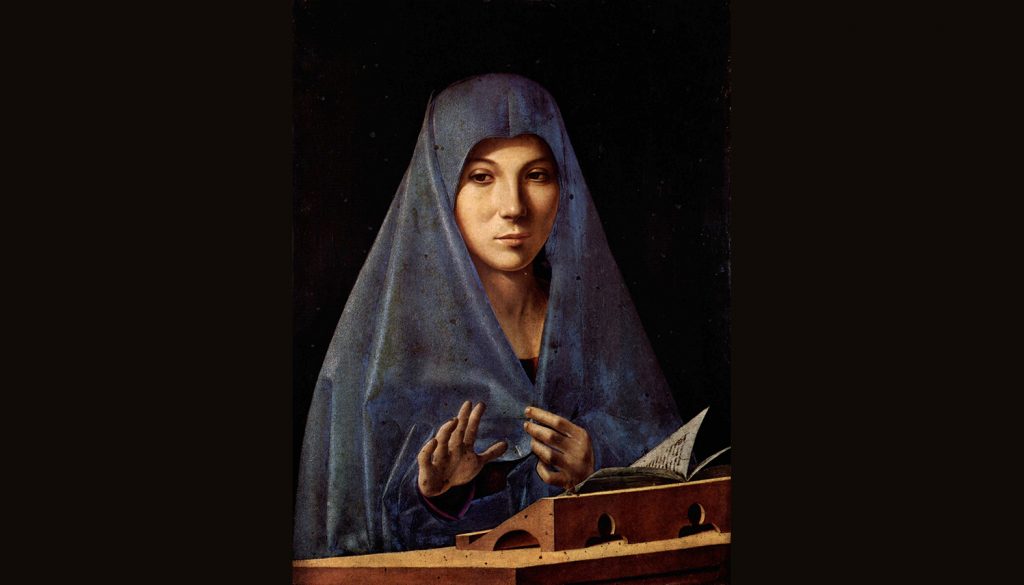

To that end, of all the wonderful art included in Auth’s book, one painting stopped me in my tracks: Antonello da Messina’s “Virgin Annunciate” (1476). Everything that painting “says” — and what it says is for me and you to ponder in our hearts — is as sustaining today as it was the day it was painted 550 years ago.

The unseen angel’s wings have fluttered the pages of Mary’s prayer book. Her right hand is raised in a firm, if uncomprehending, fiat. And her eyes gaze into a kingdom far beyond this one.

May we head toward that kingdom on our own pilgrimage.