ROME — Never let it be said that Father Charles Curran, the now 88-year-old doyen of liberal American Catholic theologians, was ever late to a party.

In April 1967, more than a year before St. Pope Paul VI’s encyclical “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”) would be published reaffirming the Church’s traditional ban on birth control, Father Curran was fired by the Catholic University of America, among other things for his liberal views on contraception. Faculty and students went on strike in protest, and Father Curran quickly was reinstated.

He would go on to be fired again in 1986, under St. Pope John Paul II, and that time it stuck. Father Curran relocated to Southern Methodist University, where he retired from full-time teaching in 2014.

In many ways, the uprising at Catholic University was a harbinger of things to come when “Humanae Vitae” finally came out. Not only were individual theologians such as Father Curran critical, but, perhaps for the first time in Church history, whole bishops’ conferences openly questioned the authoritativeness of a papal teaching. In Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Holland, and Canada, bishops’ conferences publicly suggested that Catholics in good conscience could draw different conclusions.

That history comes to mind this week in light of a dust-up involving the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy for Life, once the unquestioned stronghold of the Church’s most robust pro-life and anti-contraception forces during the Pope John Paul and Pope Benedict XVI years, but now under new management in the Pope Francis era.

Last month, the academy published a collection of papers from a conference it held last year in which some theologians argued that there’s a difference between universal moral norms, such as the birth control ban, and the pastoral application of those norms in concrete personal circumstances.

The volume brought a fusillade of criticism from conservative-oriented news platforms and on social media, from people objecting that a Vatican department would publish material that appears to call into question official Church teaching.

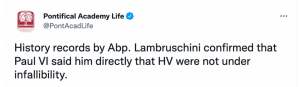

Whether ill-advised or not, the academy has chosen to enter the fray, actively dispatching tweets and other social media posts in response. On Aug. 6, one such tweet cited a 1968 press conference to present “Humanae Vitae” in which a moral theologian in Rome said it wasn’t an exercise of papal infallibility, with the suggestion being that it’s therefore subject to change.

Naturally, that tweet inspired a new and even more acerbic cycle of outrage. Before we all get too carried away, however, there are at least three points worth recalling.

First of all, a pontifical academy has no authority to proclaim definitive Church teaching, let alone a mere tweet from that academy. Neither, for that matter, does a moral theologian who was randomly tapped to speak at a press conference 54 years ago, nor do the operators of conservative media sites or individuals on Twitter, who often seem to compete with one another to see who comes off as more “Catholic” than the rest.

In the Catholic system, defining official Church teaching pertains to the pope and the bishops in communion with him, and no one else. To get overly upset about anybody else’s views, therefore, is often a bit disproportionate.

Second, the Father Curran background is a reminder that ever since “Humanae Vitae” appeared, there’s been an active controversy over exactly what level of authority it enjoys.

In general, conservatives — such as theologians Father John Ford, SJ, and Germain Grisez, in their celebrated “Theological Studies” essay in 1978 — argue that “Humanae Vitae” is de facto infallible. They point out that just because it hasn’t been formally declared as such doesn’t mean it isn’t. Historically, such formal declarations have been reserved to matters of faith, not morals, and anyway, no pope ever declared prohibitions against lying, cheating, and stealing infallible either, but that doesn’t mean it’s anything goes.

Liberals — such as Father Francis Sullivan, SJ, in his equally celebrated 1983 response to Father Ford and Grisez — insist that “Humanae Vitae” does not meet the test for infallibility, in part because no specific moral norm can be taught infallibly. Moreover, liberals often say, if either Pope John Paul II or Pope Benedict had thought the birth control ban was infallible, they could have said so, but neither ever did.

In other words, this week’s fracas with the Pontifical Academy for Life is simply another twist in a long-running story, and probably not among the most important ones at that.

Third, for popes and bishops to effectively discharge what tradition calls the “munus docendi,” meaning “the duty to teach,” they need to be informed by a robust and open theological debate, and that can’t be rushed.

If anyone’s scandalized that it’s been 54 years since “Humanae Vitae” and we’re still fussing over it, it’s worth recalling that the earliest references to the dogma of the Immaculate Conception date to the second century, yet it wasn’t formally proclaimed until 1854, and that came only after Pope Pius IX had written to all the bishops of the world five years before to ask their opinion.

If 16 centuries can pass before settling such a core matter in a way that’s beyond all question, maybe a bit of patience is in order now.

As a final thought, while a robust theological debate certainly is a service to the Church’s magisterium, one might profitably ask whether Twitter, or social media in general, is the right venue for it. Granted, it may be unrealistic to expect outfits and individuals whose income depends on keeping people angry to exercise much restraint, especially in the use of technologies whose very purpose often seems to be to provoke mass hysteria.

Perhaps, however, more could be expected from the adults in the room, including the pontifical academies of the world.