“Truly, God is in this place and I did not know it.”

— Genesis 28:16

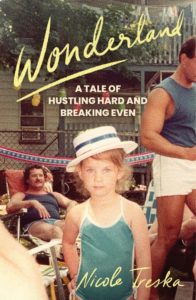

Boston native Nicole Treska has written a book to read with an ache in the throat: “Wonderland” (Simon & Schuster, $27.99).

“How do you turn the province of drunks, sailors, and hookers into a dream of bright escape?” she asks in the opening paragraph. “You build Wonderland, one of America’s first amusement parks, located on the water right outside of Boston. Wonderland only operated for a few bright seasons, from 1906 to 1910, but its legacy shines on.”

Wonderland was first an amusement park, then a ballroom, a greyhound dog racing park, and is now the last train stop on the MBTA Blue Line.

Treska uses its trajectory as a metaphor for, among other things, the developers who tore Boston apart from the late ’50s through the ’70s, destroying immigrant and ethnic neighborhoods, displacing tens of thousands, including many members of Treska’s extended Albanian-Italian family.

“Wonderland” also evokes the fierce, weirdly unique pride of place that characterizes the true lover of Boston. Most of all, it’s a stand-in for the eternal search for home and love, and the way our childhoods template that search, forever.

She spent her first seven years in and around the Treska home on Hancock Street in the then-working-class neighborhood of Somerville.

Her father, Phil, was a bookie for the notorious Winter Hill Gang mobsters. Busted at his post office job, he spent two years in federal prison for racketeering. “I never flipped on anyone, Nikki,” he tells her later. “I did good time.”

Her mother, Christine, is tough, too, taking bets over the phone, but walks out on Phil when he gets a little too free with his fists.

With her mother, her younger sister, and their stepfather, Treska spends the next decade of her formative years moving around the country: Texas, Virginia, Hawaii.

“We’re a family full of runners from a city of runners. We get … out of there. We moved and set up somewhere safe and make ourselves real until we have to do it again.”

But her heart, for better or worse, is always in Boston: back with Phil, the Pats, the North End’s Regina’s Pizza, and the coke-snorting aunties with feathered hair and bomber jackets, “all mouth,” who helped raise and form her.

Flying into Logan, she cries at the sight of the familiar red-and-white tower of the Soldiers’ Home.

In 2008, she moves to Manhattan, begins teaching English at The City College of New York, and rents out the bedroom of her tiny Harlem apartment on Airbnb, making a decent living for the first time in her life.

She’s escaped — kind of — but she still visits her mother in Florida, the old haunts in Boston. Family memories are selective, distorted to protect the innocent, or conveniently erased. Did Phil sew drugs into the stomach of her beloved stuffed Doggie to sell on the Somerville streets while little Nikki lolled in her stroller? Maybe, depending on who’s telling the story — including Phil — maybe not.

Her father — in recent years, usually needing money — is easy to love, easy to hate. How to balance the two? Do you love the person who’s harmed you? Can you ever trust the person who’s known to lie? Do you become hardened, or do you allow yourself to be vulnerable and open, to yearn and long?

Aunt Loretta, Phil’s sister, cherished and wounded, was a casualty of the family secrets, violence, and dysfunction. Treska has said that in a way she wrote the book partly in homage, so that Loretta’s life would not be invisible, forgotten.

The last time she saw her aunt was in late 2008. Nicole, her younger sister Lindsay, and Phil visit Loretta in the Saugus mental home where she lives.

They drive north from Boston, through a strip of Route 1 lined with landmarks dear to the heart of anyone who grew up in the area (as I did): the Leaning Tower of Pizza, Frank Giuffrida’s Hilltop Steak House, Kowloon Chinese restaurant, the giant orange T. Rex looming over the Route 1 Miniature Golf and Batting Cages.

“Route 1’s stops and signage managed to conjure a world bigger than the one we knew — the Far East, the Wild West, prehistory, Europe. Those holy restaurants off the highway promised us the big lights and far-flung places we might not otherwise see. There is some insistence of Bostonians, across generations, to live a life grand enough for the grandeur they feel. … My parents thought they were destined for greatness, even though greatness wasn’t readily available to them. I liked to think that this was why they went after life so audaciously. I liked to think I inherited this from them.”

Loretta is thrilled to see them. They check out her room, the coat Phil bought her at the Burlington Mall, the rafts of old photos.

“In the bathroom, her Wet ’n’ Wild lipstick was on the sink with a can of Aqua Net and a collection of her medications. Just like at Hancock Street. And what was a life, really, but a collection of cosmetics, old pictures, and little plastic bottles? We carried what we could, and Loretta couldn’t carry much. Each item in her little room was a totem, blessed by its mere existence, its survival.”

Can we ever truly escape our past? Do we really want to?

Over crullers and coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts afterwards, Aunt Loretta — heedless of the other patrons — belts out a family favorite: Dean Martin’s “Non Dimenticar”: Don’t Forget.

Nicole Treska hasn’t forgotten anything.