The first thing to realize about the U.S. bishops’ concern with pro-choice Catholic politicians who receive holy Communion is that, from the bishops’ point of view, the issue isn’t politics, but, rather the reverence due the Eucharist and the perilous spiritual situation of someone who receives the sacrament unworthily.

It’s true, of course, that nobody really deserves the Eucharist. But Christ has given us this gift, and we ought to receive it — provided we do so with clean consciences. And for supporters of abortion, there’s the rub. For advocating this grave moral evil (or a ‘right’ to choose abortion, which amounts to the same thing) is a form of participation in the evil.

In his first letter to the Christians of Corinth, St. Paul pointed out the consequences that has for receiving Communion: “Whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. … Any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself” (1 Corinthians 11: 27, 29).

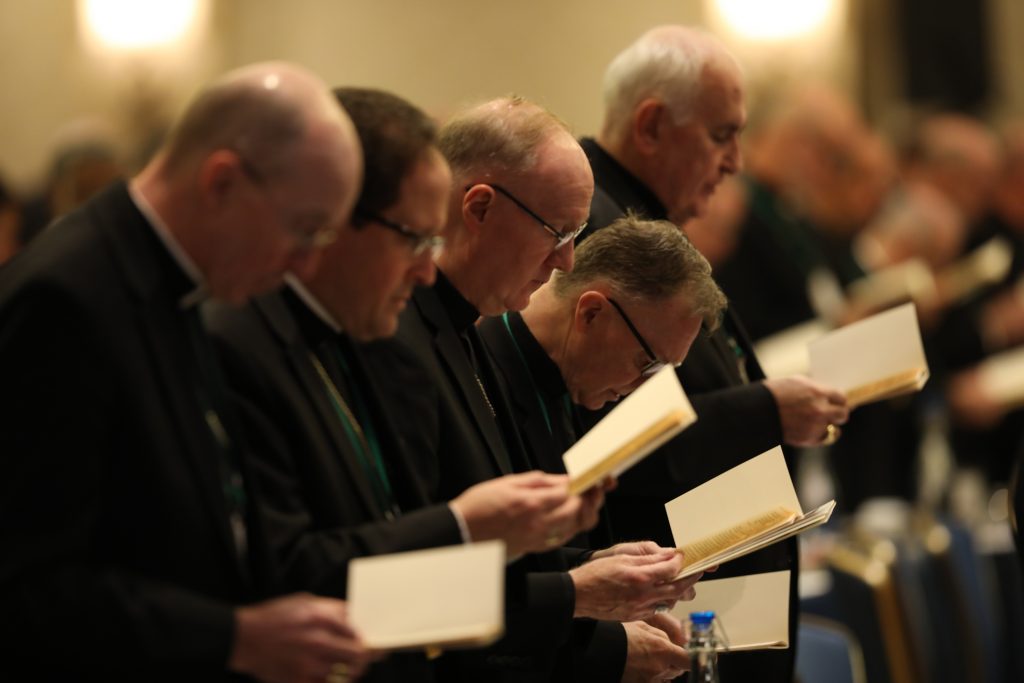

Here, then, is the context in which the bishops at their June 16-18 general meeting are expected to discuss (virtually, because of the pandemic) whether to proceed with developing a statement on “eucharistic coherence” to address these matters at length.

It won’t be the first time the bishops have had essentially the same discussion. Back in 2004, when a pro-choice Catholic, John Kerry, was running for president, then-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, chairing a committee charged with looking into the issue, told the bishops that refusing Communion to Kerry would make the sacrament “a perceived source of political combat.”

Notably, too, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and later known to the world as Pope Benedict XVI, sent the bishops a letter (which McCarrick declined to show them) saying someone who persists in serious public sin should be denied Communion. The bishops eventually decided to leave it to individual ordinaries to decide how to handle this problem in their own dioceses.

And now the problem has come to a head in the case of a sitting president.

In his long career as senator, vice president, presidential candidate, and now chief executive, Joe Biden’s position on abortion has changed radically over the years — and from a pro-life perspective, the change has all been for the worse.

In 1973, after the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion, Biden expressed reservations about what the court had done. Then, for four decades he supported the Hyde Amendment barring the use of federal funds for abortion. Two years ago, however, under pressure from abortion activists, Biden reversed on Hyde and promised that as president he’d get rid of it.

During the presidential campaign he said he supported abortion “under any circumstances,” promised to make the Roe decision federal law, and chose aggressively pro-abortion California Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate. Since becoming president, he and his administration have acted repeatedly to expand the availability of abortion.

At the same time, Biden, a lifelong Catholic, continues to declare his allegiance to the faith and receives Communion at Sunday Mass. According to critics, that is something he simply shouldn’t do, in light of the Church’s clear teaching on abortion and the prohibition in canon 915 of the Code of Canon Law, which says people “who obstinately persist in manifest grave sin are not to be admitted to Holy Communion.”

Taking note of all this, Archbishop José H. Gomez of Los Angeles, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), last year set up a working group chaired by the conference’s vice president, Archbishop Allen Vigneron of Detroit, to make recommendations on how to proceed. It proposed writing and publishing a statement on “eucharistic coherence,” outlining why Catholics who receive Communion should live and act in a manner consistent with the faith of the Church.

Whether to proceed with a statement is the question the bishops are expected to face at their June assembly. And here there is disagreement.

Several bishops lately have issued statements of their own strongly arguing that politicians who support abortion should not receive Communion. One of them is Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone of San Francisco, whose archdiocese is home to another well-known pro-choice Catholic politician, Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi.

Addressing Catholics who publicly support abortion, Archbishop Cordileone closed his strongly worded pastoral letter this way: “If you find that you are unwilling or unable to abandon your advocacy for abortion, you should not come forward to receive Holy Communion. To publicly affirm the Catholic faith while at the same time rejecting one of its most fundamental teachings is simply dishonest.”

But some bishops — how many are not known — don’t want the bishops’ conference to make a statement. Echoing McCarrick in 2004, they warn that anything the bishops might say or do on this issue would be viewed as playing politics.

Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego has been particularly outspoken in making this argument. Speaking during a panel discussion earlier this year, he said this: “I do not see how depriving the president or other political leaders of the Eucharist on their public policy stance can be interpreted in our society as anything other than a weaponization of the Eucharist … to pummel them into submission.”

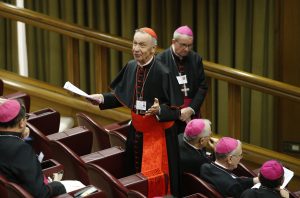

A third position, somewhere between the strongly for and the strongly against, was laid out by Cardinal Luis Ladaria, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in a letter sent to Archbishop Gomez in early May.

Cardinal Ladaria expressed general approval of the idea of a bishops’ statement that would underline “the grave moral responsibility of Catholic public officials to protect human life at all stages” while repeating that decisions about how to proceed at the local level are up to ordinaries.

He added that the statement should be preceded by dialogue among the bishops and consultation with other episcopal conferences; should point out that abortion and euthanasia aren’t the only issues of concern to the Church; and should make it clear that worthiness to receive Communion applies to all Catholics, not just public officials.

That latter point is a reminder that the issue of Communion for pro-choice politicians exists in the context of a larger problem — growing concern that respect for the sacrament may have diminished among Catholics generally as evidenced in declining Mass attendance and poll numbers suggesting that many American Catholics think Christ’s presence in the Eucharist is only symbolic, not real.

Archbishop Samuel Aquila of Denver spoke to that issue in a recent article in America magazine.

“I am afraid that many baptized Catholics do not take the Eucharist seriously because they do not take sin seriously,” he wrote, adding that this was “largely the fault of bad catechesis overseen by me and my brother bishops for too long.”

“When the Eucharist is treated casually in our liturgy, minimized in the confessional or ignored in homilies, then we should not be surprised by confusion regarding its sacredness. … In this respect, the ministers of the faith have, perhaps, the greater responsibility for improper reception of the Eucharist,” he said.

One thing at least is clear. When the bishops discuss “eucharistic coherence” at their June general assembly, they’ll have plenty to talk about. It should be an interesting discussion.