“Magellanica” is a five-part, four-hour audio drama, streaming for free through June 30 on Apple Podcast, Spotify, Stitcher, and other major podcast platforms.

Adapted by the award-winning playwright E.M. Lewis from her 2018 world premiere play, the drama is based on an actual expedition: the scientists and engineers, led by American climatologist Susan Solomon, who converged at the South Pole Research Station in 1986 in order to study the effect of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) on the atmosphere.

The thumbnail: “In the darkest, coldest, most dangerous place on Earth, eight imperfect souls are trapped together and utterly isolated from the outside world for eight and a half months. This tiny, international community meets as strangers and must face life or death challenges, their own inner demons, and depend upon each other for survival.”

In other words, this is one perfect way to ponder the last year as we segue back into “normal” life.

Throughout, Rodolfo Ortega’s composition and sound design are first-rate, plunging listeners into an alternative universe.

To avoid getting muddled, especially at the beginning, it’s useful to have a list of the cast and crew: Vin Shambry as Captain Adam Burrell, a Vietnam vet; John San Nicolas as Freddie de la Rosa, Burrell’s assistant; Sara Hennessy as Dr. Morgan Halsted, there to prove that CFCs are making a hole in the sky; Michael Mendelson as Dr. Vadik Chapayev, there to prove there is no hole in the sky; Allen Nause as Dr. Todor Kozlek, cartographer; Barbie Wu as Dr. May Zhou, researching the Southern Lights; Eric Pargac as Dr. Lars Brotten, an expert on penguins; and Joshua J. Weinstein as Dr. William Huffington, British, glacier specialist.

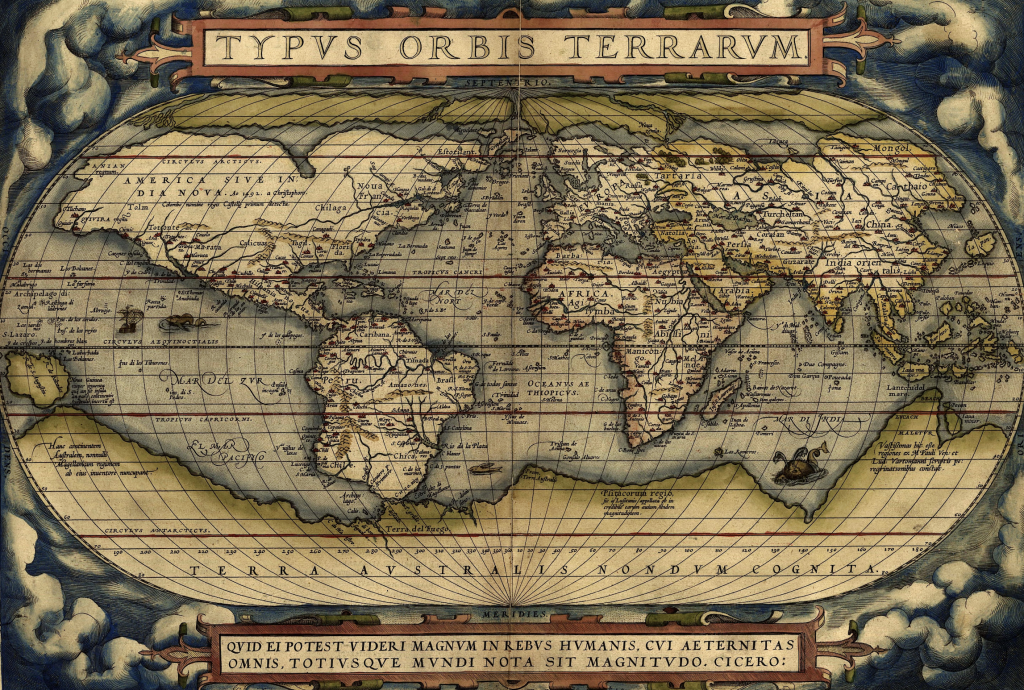

Magellanica is the name of a mythic continent, a phantom “Southland,” that appeared on world maps in the 15th through 18th centuries.

Kozlek is obsessed with mapping just such an undiscovered country: “I begin to see how maps have power … purposes. …” Where are we in space, in time, in eternity?

In fact, these are poets and philosophers as much as they’re scientists. “Scientific experiments are supposed to be filled with wild imagination,” a crew member proposes.

As the drama unfolds, the light wanes. Two weeks after landing, on March 17, 1986, the crew begins to experience “civil twilight” — the period in the year when there is enough light for ordinary outdoor occupations.

There’s an 11-day storm. Who goes out in the storm to seek help with the generator? Who stays back to care for a crew member who is sick? Is it more courageous to go or to stay?

The scientists begin to realize there is a hole in the ozone layer, that the earth is in danger.

Halsted, an American, and Chapayev, Russian, conduct a semi-drunken debate about nationalism, political systems, where the other’s country has gone wrong.

Poignantly, various personal items have been brought on board. A grandmother’s cookbook. A gramophone and the music of Shostakovich. Kozlek dreams of having brought “the whole world,” a globe in a tiny box: a map of the heavens made in 1731 with its own matching case.

The days and weeks pass. In “nautical twilight,” the stars are visible and the horizon is clearly defined.

A telescope breaks. A fistfight breaks up. People miss their families.

Gnomic pronouncements are made: “Always make friends with librarians: awkward people who carry the keys to the universe.”

Existential questions are asked: “What am I seeing that the machines that hum and hum cannot tell me?”

Word comes through that someone’s father has died. The anguish of not being able to go home.

In their way, the crew members care for one another. They show compassion; they also call one another to account.

By April 22 astronomical twilight has begun. It’s dark all the time. Everyone is in their room all the time but nobody sleeps. “There is something in the air.”

When Kozlek sleeps, he maps the monsters of Magellanica and travels forward to the future, all the way to this time now in the Arctic.

“We treat this world as if it were endless, but it’s not endless.”

“If I were not so full of wonder, I might be full of terror.”

The hours of daylight become shorter and shorter.

“It’s like a rocket ship or a submarine or a prison. The darkness is beginning to press in.”

The solstice looms: June 21. “The greatest darkness. The longest night. It’s not about the darkness. This is the tipping point, when everything changes.”

They schedule a celebration: the Mid-Winter Follies. Everyone is tasked with bringing something: a story, a song, a poem. May worries that her offering won’t be worthy.

“Is the darkness calling me?”

“Where are we?”

“This is a ghost story,” observes Brotten at one point. “This is a story full of ghosts.”

The ghosts ask: What is our responsibility to ourselves and to one another? How will we survive? Where are we in time and space?

But most to the point: Where are we in relation to the people nearest to us, next to us?