In “Abandonment to Divine Providence,” 17th-century priest Father Jean-Pierre de Caussade, SJ, observed:

“Since the world began, its history is nothing but the account of the campaign waged by the powers of the world and the princes of hell against the humble souls who love God. It is a conflict in which all the odds seem to favor pride, yet humility always wins. …

“The war which broke out in heaven between St. Michael and Lucifer is still being fought. … Every wicked man since Cain, up until those who now consume the world, have outwardly appeared to be great and powerful princes. They have astonished the world and men have bowed down before them. But the face they present to the world is false. …

“All ancient history, both sacred and profane, is only the record of this conflict. The order established by God has always conquered, and those who have fought with him enjoy eternal happiness. … If one solitary soul has all the powers of hell and the world against it, it need fear nothing if it has abandoned itself to the order of God.”

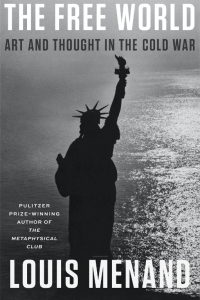

I thought of that passage as I read “The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35.00) a newly published 727-page tome by public intellectual and cultural critic Louis Menand.

I didn’t read the whole book because halfway through I realized that Menand was going to present a bunch of people from the U.S and Europe during the 1950s and 1960s with whom I was mostly already at least vaguely familiar. Period.

The book has no slant, no take, no thesis, no theme. No point-of-view. No argument. No order: no idea more noteworthy, interesting, or absurd than another.

Sure, he packs in the information and lively, carefully chosen anecdotes. The breadth of his research is staggering. The Footnotes alone run to almost 100 pages; the Index another 40. But if you’re a child of the ’50s and ’60s, or anywhere near it, you’ve been reading about these individuals all your life.

John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, George Kennan, Simone de Beauvoir, James Baldwin, Diana Trilling, Bob Dylan, Hannah Arendt, Jack Kerouac, Jackson Pollock, Clement Greenberg, and the Beatles, to name just a few — are all presented in the same neutral, faintly gossipy, tone.

No life is more worthy of censure on the one hand (except in the case of gross stupidity or harm), or of respect and admiration on the other.

Menand himself seems not much to admire any of them. Is he saying that, given an unlimited amount of freedom, this somewhat uninspiring group — the way he paints it, anyway — is the best that post-World War II Western civilization has been able to produce?

If so, in a way, I agree with him: But what could possibly have prodded Menand — free to write whatever moves him — to spend what had to have been years researching and writing such a book?

What he left out, as opposed to what he included, may provide one kind of answer. While mentioning hundreds of figures from politics, science, economics, public thought, and the arts, he barely mentions religion of any kind, much less Catholicism.

Graham Greene, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Thomas Merton: silence. Vatican II — nada. The 20th-century martyrs in the Gulag, Nazi Germany, Poland — who cares? The Berrigan brothers, St. Pope John Paul II, Dorothy Day — not important.

Not, perhaps in Menand’s mind, “free?”

I thought of a friend of mine who, in her 50s, has gone back to school and is earning her master’s in a “helping profession.” She spends an hour each morning in eucharistic adoration, then attends classes uniformly undergirded by woke ideology. She’s the oldest student in her program, and within a week had been taken to task by her professor in front of the class for being a racist, simply by virtue of being white.

She didn’t bother to tell them that she’s a widow with two teenage sons and that her late husband was Black. She simply stood her ground and said, “That hurts my feelings. It’s not true and please don’t say it again.”

The conflict continued for some months. My friend stayed the course. “I just try to bring Christ to class,” she told him. “What does he want from me? What is the deepest desire of my heart?”

She asked for a couple of one-on-one Zoom conversations with her professor. She began to like him, and vice versa. Over time, a shift occurred. She saw that her fellow students were floundering. They were like sheep without a shepherd. Her heart opened to them.

“God gave me the gift to love my fellow students as they are; an awareness of who they were for me. I realized their existence — the very fact that they exist — is more important than any disagreement I might have with them. “

“They see there’s something different about me, something they can’t quite put their finger on.”

One day she told them simply, “My life is interiorly ordered.”

That’s thought. That’s life as art. That’s freedom — in the Cold War, or at any other time in history.