New York Times best-selling author and Catholic Arthur C. Brooks believes there is an “outrage industrial complex” that prospers by setting American against American.

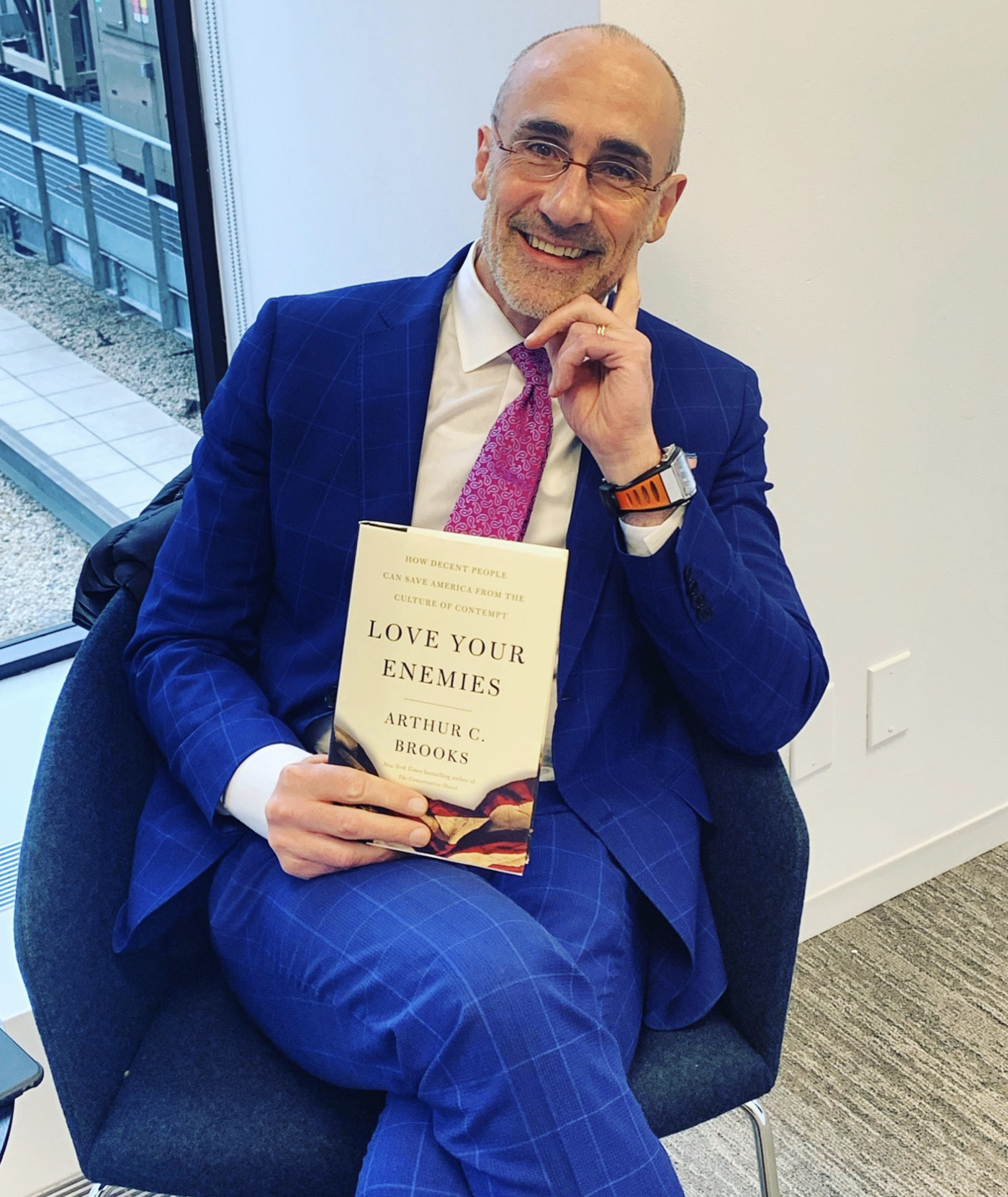

“America is addicted to political contempt,” he writes in his newly published book, “Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt” (Broadside Books, $28).

“While most of us hate what it is doing to our country and worry about how contempt coarsens our culture over the long term, many of us still compulsively consume the ideological equivalent of meth from elected officials, academics, entertainers, and some of the news media,” he observes.

In an interview with Angelus News, Brooks shared his thoughts about how the Dalai Lama inspires him, why he believes civility and tolerance are “garbage standards,” and the priest that saved him from cynicism.

Kathryn Jean Lopez: Can decent people really save America? Do we even know what to do with decency anymore?

Arthur Brooks: The funny thing about our political moment is that while it looks like there is no market for decency in public life, in reality the vast majority of Americans hate our current culture and want it to change.

Ninety-three percent of the country can’t stand how divided we’ve become. In other words, it’s not that we should be looking to the few decent people left to save America; it’s that we need to remember that the country is full of decent people — we just don’t all agree on matters of public policy.

What we have to realize is that the caricatures of our ideological opponents that we see on social media and in the news are not representative of the beliefs and behaviors of the American people.

Lopez: Who are the most decent people you know, who you look to on days when your faith in your book’s theme might be tempted to waver?

Brooks: In writing this book, one of my most important sources of inspiration was my friend and occasional co-author, the Dalai Lama. His own story is an important reminder for me when I am treated with contempt and want to respond in kind.

Though he and his people have been persecuted by the Chinese government since his teenage years, the Dalai Lama prays for the leaders of China every morning, that they would lead good and happy lives.

His advice to me has been similar: When you are treated with contempt, practice warmheartedness. This might sound like soft and weak advice, but as I’ve learned from the Dalai Lama, being a person of warmheartedness in fact requires great strength and toughness. Strange to say, the Dalai Lama has made me a better Catholic.

Lopez: “Political scientists find that our nation is more polarized than it has been at any time since the Civil War.” Does that worry you, that people talk in those terms? Did you hesitate to put it in the book?

Brooks: It certainly worries me! When the data show that 1 in 6 Americans has stopped talking to a close friend or family member because of politics, you know that things are not as they ought to be.

But that’s why I wrote this book — because I believe we have a real problem, I think the worst thing we could do is ignore the problem, and I want to offer public leaders and ordinary citizens alike a series of practical strategies for fighting the culture of contempt.

Lopez: And yet you name civility and tolerance as “garbage standards.” How is love the game changer and is it really practical in politics?

Brooks: In its truest form, love is not soft or sentimental. It is a clear and bracing commitment to the good of our fellow men and women. It holds us to a higher standard.

If a married couple told you they were civil with one another, you’d probably think they needed to go to counseling. If your colleagues at work merely tolerate you, you’re probably looking for a new job.

In other words, we set the bar too low when we strive for civility and tolerance. There’s nothing wrong with civility and tolerance, per se, but they do not require that we actively will what is good for the other (as St. Thomas Aquinas put it), which is what we need to make genuine progress.

To the second part of your question, relying on the principle of love is practical in politics because it provides a moral consensus around which meaningful disagreement can revolve. If we know that our fellow citizens genuinely will what is good for us, we can have the kinds of policy debates that will allow us to solve the many challenges our country faces.

Lopez: Why is it so important not to misdiagnose the contempt all around as anger?

Brooks: There’s an important psychological difference between anger and contempt. When you get angry at someone — maybe a friend, a spouse, or a colleague — what that says is, “I care about this, and I’m mad because I see that something is wrong and want to fix it.”

Contempt, on the other hand, says, “You are beneath caring about.” Anger ultimately helps us reconcile, but contempt makes permanent enemies.

This is a critical distinction with respect to America’s political environment because it shows that there’s nothing inherently wrong with being angry and disagreeing, but that if we want to bring the country back together, contempt is the surest way to keep it from happening.

Lopez: “None of us has a monopoly on truth.” Is your listening to the other side’s advice going to work when the other side has contempt for you and facts?

Brooks: The answer to this question is slightly counterintuitive, because what we need to understand is that contempt is an opportunity — an opportunity to change your own heart through your actions, no matter how you feel about the people with whom you disagree.

The contempt we see all around us is discouraging, but treating others with love and respect is your only shot at persuading people who think differently than you.

No one has ever been hated or insulted into agreement, and we can all be more effective in our disagreements with others if we keep that in mind. This insight has really changed my life.

Lopez: You write that “[w]e need national healing every bit as much as economic growth.” And everyone can truly lead on this front?

Brooks: Certainly. We need better leadership at the state and national level and in media, to be sure, but what this book calls for is a personal transformation. If we turn toward greater love and happiness, it will be reflected in our market and voting choices. The “leaders” will follow.

Lopez: You describe gratitude as a “contempt killer.” Is it also essential to love and any progress?

Brooks: Not only to love and progress, but happiness as well. There’s no shortage of research showing that when we choose to express gratitude, we become happier as people. So at a practical level, showing gratitude for others will make you more persuasive and effective, but it will also improve your individual well-being.

Lopez: Your book is about the culture of contempt in politics, but practically speaking, does everyone have enemies? Do you have handy spiritual practices for keeping yourself in check around them outside the political/policy battlefield?

Brooks: In a way, the title of the book may be a little misleading. My point is not actually that we are surrounded by enemies, but rather that we incorrectly assume we are surrounded by enemies (who are in fact just fellow Americans who disagree with us on policy and politics).

But our responses to those who disagree with us should be informed by the exhortation of Christ in Matthew 5:44 to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us. This is not only the morally right thing to do; it’s also a highly effective strategy.

Throughout history, we’ve seen that the most lasting victories are brought about by leaders who embraced the principle of love, none more so than Dr. Martin Luther King. To love others doesn’t mean rolling over or settling for more agreement (as King’s example demonstrates); but it does require treating everyone — especially those who disagree with us — with dignity and respect.

Lopez: You and your wife teach marriage prep. Why is that a priority for you?

Brooks: Ester and I believe that the flourishing of our country and our community rests on the foundation of strong families, so we want to contribute to our society in that way.

But more importantly, we have been blessed to have mentors who have helped us strengthen our marriage, and we want to similarly help couples prepare for life together and understand the critical role that their faith will play in sustaining the relationship.

Lopez: How has adoption changed your life?

Brooks: Adopting our youngest daughter was one of the best decisions we’ve ever made, even though it seemed a little crazy at the time. (I had just written a book about how giving to charity and volunteering to serve others makes us happier. My wife’s response to the book? “I’ve read that there are millions of girls without parents in China. I think we should adopt one!”)

Our faith tells us that it is our responsibility to love and serve others, and to extend the welcome of family to as many people as we can. That’s what we were hoping to do when we adopted our daughter, and that decision has been a profound blessing for each person in our family.

Lopez: You dedicate the book to a priest we both knew, Father Arne Panula. How did he teach you to love your enemies?

Brooks: If you’re not careful, living in a town like Washington, D.C., can make you cynical, calculating, and even just plain mean.

I met with Father Arne for spiritual direction every month for a decade after I made the move to the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in 2009, and he showed me time and again that the surest way to bring about change and make a difference in people’s lives is to show love and kindness to everyone.

Most importantly, he would remind me that I should be extending love not just to my friends, but to those with whom I had the greatest differences, political or otherwise. His guidance had an enormous influence on my thinking and my time leading AEI, and I’m so grateful for the example he set for me and so many others.

Kathryn Jean Lopez is a contributing editor to Angelus, and editor-at-large of National Review Online.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!