“Has anybody here seen my old friend Martin? Can you tell me where he’s gone? He freed a lotta people, but it seems the good die young. But I just looked around and he’s gone.”

— “Abraham, Martin, and John” by Dion

My family and friends know that part of the reason that I went to Harvard was because I’ve always loved the Kennedys. And yet the only poster on the wall of my freshman dorm room was that of a King.

I had bought this giant 3-foot by 4-foot black and white poster of Martin Luther King Jr. at a poster shop back home in Fresno. And, when I got back to Cambridge, I couldn’t wait to put it up in my room.

Even then, as an 18-year-old fresh out of the farm country of Central California, I had respect for the “non-compromiser” — the person who stands his ground, even against impossible odds, rather than give in to tyranny and accept injustice or unequal treatment.

Even then, I appreciated those who refused to bend, or wait, or accept excuses for why change missed the train and is running a week late.

I admired those who were willing to break unjust laws and, if necessary, go to jail for whatever they believed in — consistent with the traditions of notorious rabble-rousers such as Mahatma Ghandi and Henry David Thoreau — because they answered to a higher power.

Add to that the fact that I was getting ready to change my major to American History. I started out as a Government major — a “gov jock” as they were called at the time.

But a freshman year course in political philosophy, where it seemed just about any action could be justified, was enough to make me hungry for a discipline that seemed to be more black and white, where the things that drive people are either right or wrong.

King was in the right. And those who opposed him, or fought him, or stalled him, or tried to pacify him were in the wrong.

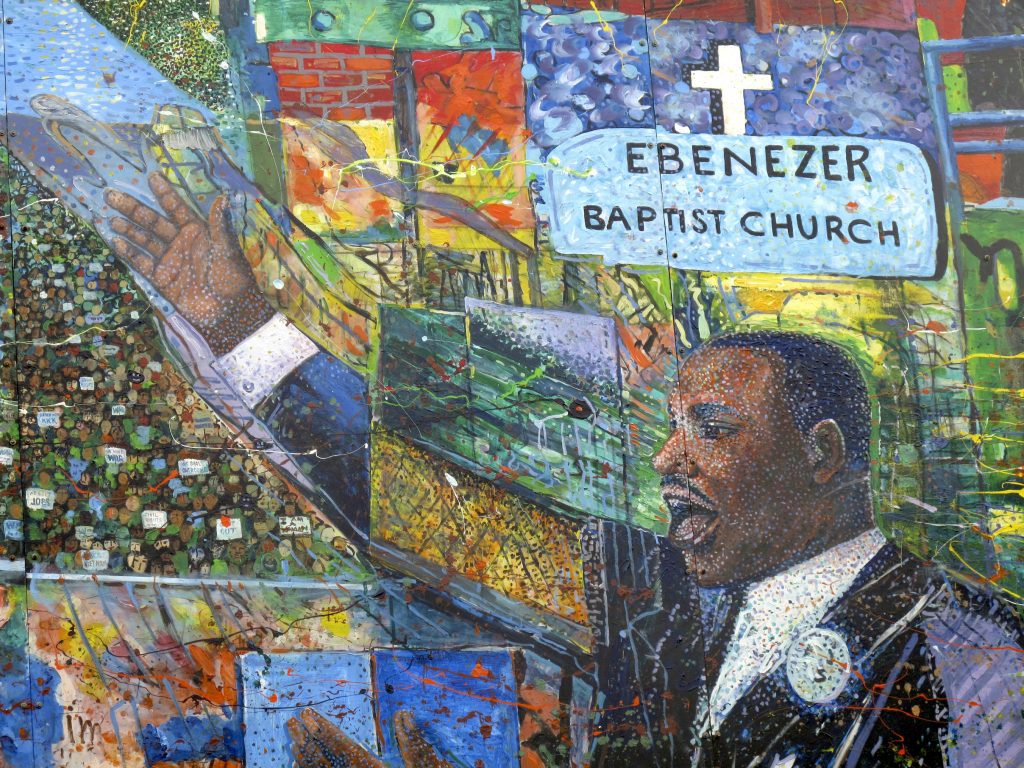

Who could have known that the charismatic young minister who, in the 1950s, preached from the pulpit each Sunday from the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta would rise to help lead his people out of bondage? And who could have imagined that, in doing so, he would help free the rest of America to keep its promises and live up to its creed?

Here you had this odd mixture of a soft-spoken, deliberate, calm man of God who — once the switch was flipped — was transformed into one of the greatest orators of the 20th century.

From the moment that King traveled to Montgomery to launch a boycott in support of a young black seamstress — Rosa Parks — who refused to give up her bus seat to a white man, to his arrest in October 1960 for participating in a sit-in at a segregated Atlanta department store and his release when a certain Democratic candidate for president from Hyannis Port asked Georgia Gov. Ernest Vandiver to spring him, King couldn’t escape the pull of the Civil Rights Movement.

These two entities were destined to fuse together and become one.

And by the time August 1963 arrived, and King delivered his iconic “I Have A Dream” speech on the National Mall in Washington, the minister had solidified his position as one of the major leaders of the movement and a larger-than-life figure in U.S. history.

That’s the person we honor today with a national holiday.

When I think of King, I go back to my favorite quote, which explains his life’s philosophy. The reverend said: “A man has not started living until he can rise above his own individualistic concerns to the broader concerns of all humanity.”

I used that quote in my speech as a high school valedictorian to urge my fellow graduates to break out of the narrow confines of their world, and to be willing to fight what might at first appear to be someone else’s fight.

And, here I am, nearly 40 years later, and I’ve never forgotten those words.

These days, we all need to remember them. We need King more than ever. Our country has fallen on hard times.

Americans are divided into tribes with little to no empathy. We’re convinced that our experience is unique, our burden unmatched, and our perspective without flaws. We don’t care much for our fellow man, and we care even less if he comes from a foreign land. Sometimes it seems that half the country can’t stand the other half.

We’re the lost sheep of the continent. Too many Americans can’t see the broader concerns of all humanity because we’re hopelessly trapped within our own individualistic concerns.

When will we heed the preacher’s sermon? Folks, it’s time to start living.

Ruben Navarrette is a contributing editor to Angelus and a syndicated columnist with The Washington Post Writers Group and a columnist for the Daily Beast. He is a radio host, a frequent guest analyst on cable news, and member of the USA Today Board of Contributors and host of the podcast “Navarrette Nation.” Among his books are “A Darker Shade of Crimson: Odyssey of a Harvard Chicano.”

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!