Seventh in a series on the Book of Psalms.

In my last column, I mentioned that some scholars reject the Church’s “Christological” reading of the psalms. I disagree with them.

As a theologian, I protest because tradition demands that we discover Christ in the Old Testament texts. According to the Church Fathers, the truths of the Incarnation were already present “in mystery” from the first moments of creation. God had been preparing the events of Jesus’ life from all eternity. To see Christ in the Old Testament, then, is to discern, with 20-20 hindsight, the workings of divine providence.

Jesus himself read the Old Testament this way. He referred to Jonah (Matthew 12:39), Solomon (Matthew 12:42), the Temple (John 2:19), and the brazen serpent (John 3:14) as signs pointing to himself. In Luke’s gospel, he took “Moses and all the prophets” and interpreted for his disciples “what referred to him in all the Scriptures” (Luke 24:27). St. Paul read the Hebrew Scriptures in the same way (see Romans 5:14, Galatians 4:24), as did St. Peter (see 1 Peter 3:20-21).

This approach prevailed through centuries, even in places like Antioch, whose school emphasized the literal-historical meaning of biblical texts. St. Augustine summed up this method in a single phrase: the New Testament is concealed in the Old, and the Old is revealed in the New.

But the historical reasons for preserving the Christological reading of the “Psalter” are as compelling as the theological reasons. For the Christian interpretive tradition is an organic development of the Jewish exegesis of Jesus’ contemporaries.

The Jews of the first century lived in anticipation of the arrival of God’s Messiah, the redeemer who would restore the Davidic kingship over the reunited 12 tribes. “Messiah” (“Moshiach”) is Hebrew for “anointed”; its Greek equivalent is “Christos” — in English, “Christ.”

Consider the situation of Second Temple Judaism. Though a remnant of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin had returned to the land, 10 tribes of Israel remained in dispersion. The Temple itself was a shadow of what it had been. The Jews were ruled by a succession of foreign powers: Persian, Greek, and Roman.

David’s line was apparently snuffed out at the time of the Captivity (see 2 Kings 25:7), but the Jews never ceased hoping for God’s intervention. For the Lord had promised that a king in David’s line would one day rule all the nations, and he would reign forever (2 Samuel 7:12, 14).

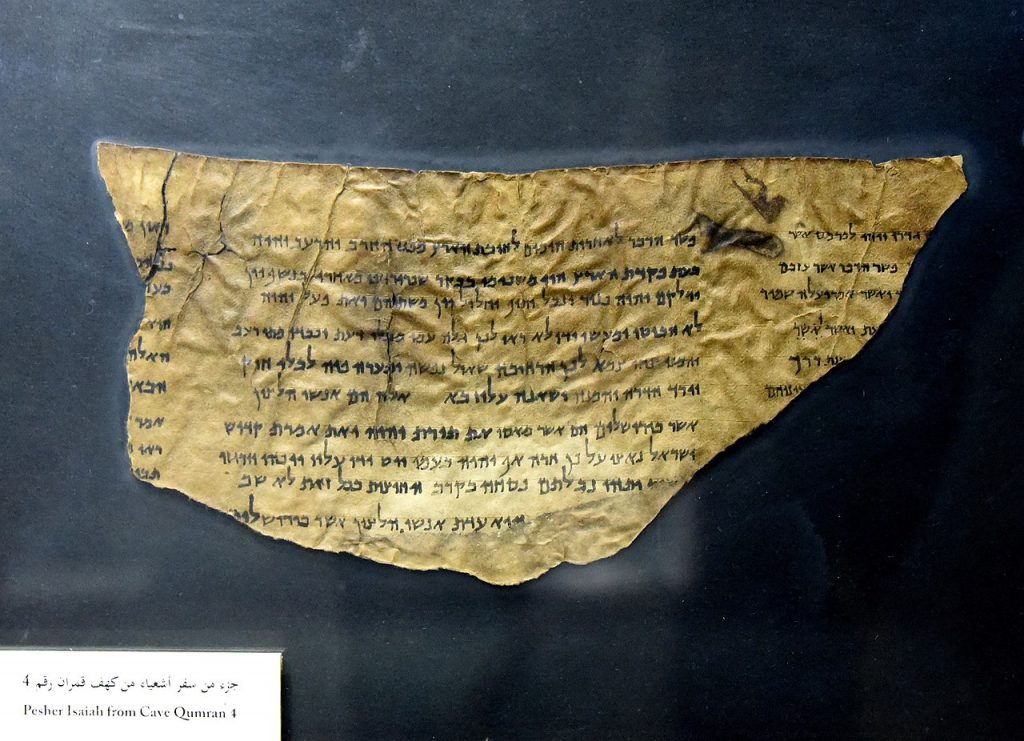

There were many messianic pretenders, and most of them met a bad end, but the people kept hoping. The messianic reading of the Old Testament is evident in many ancient Jewish texts — the Book of Enoch, the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, the Sibylline Oracles, and the Dead Sea Scrolls, among others.

But nothing expressed Israel’s longing as well as the “Psalter.” As liturgical hymns, the psalms were effective in sustaining Israel’s culture. They renewed a climate of expectation.

This is the plain sense of history. Israel’s own reading of the Psalter was messianic, and therefore Christological. If theology urges us toward a messianic reading of the psalms, history shows us that such a reading is not a Christian innovation.