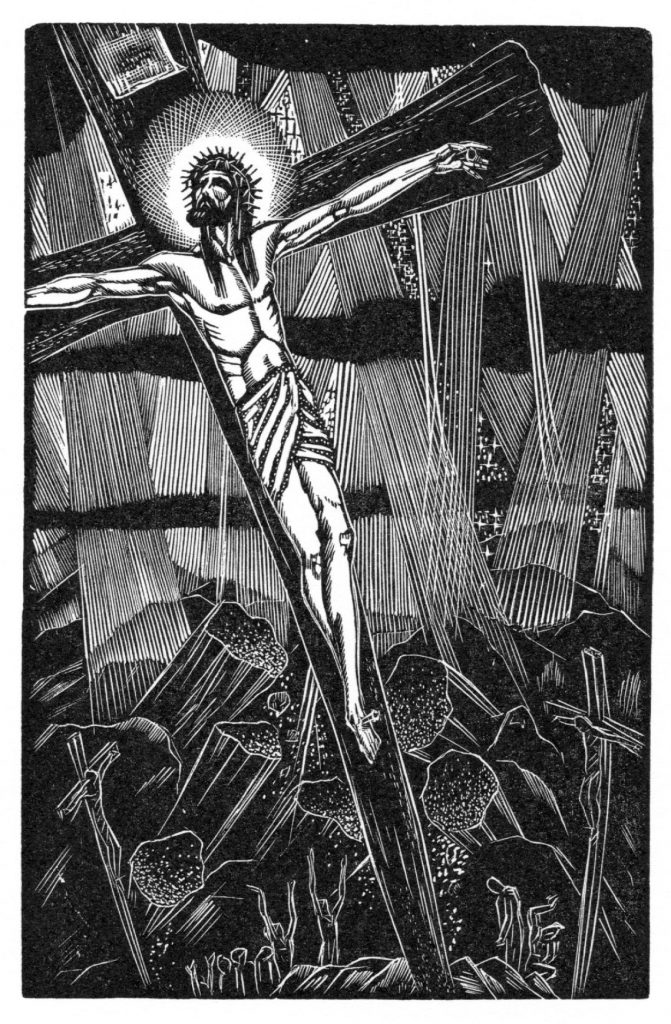

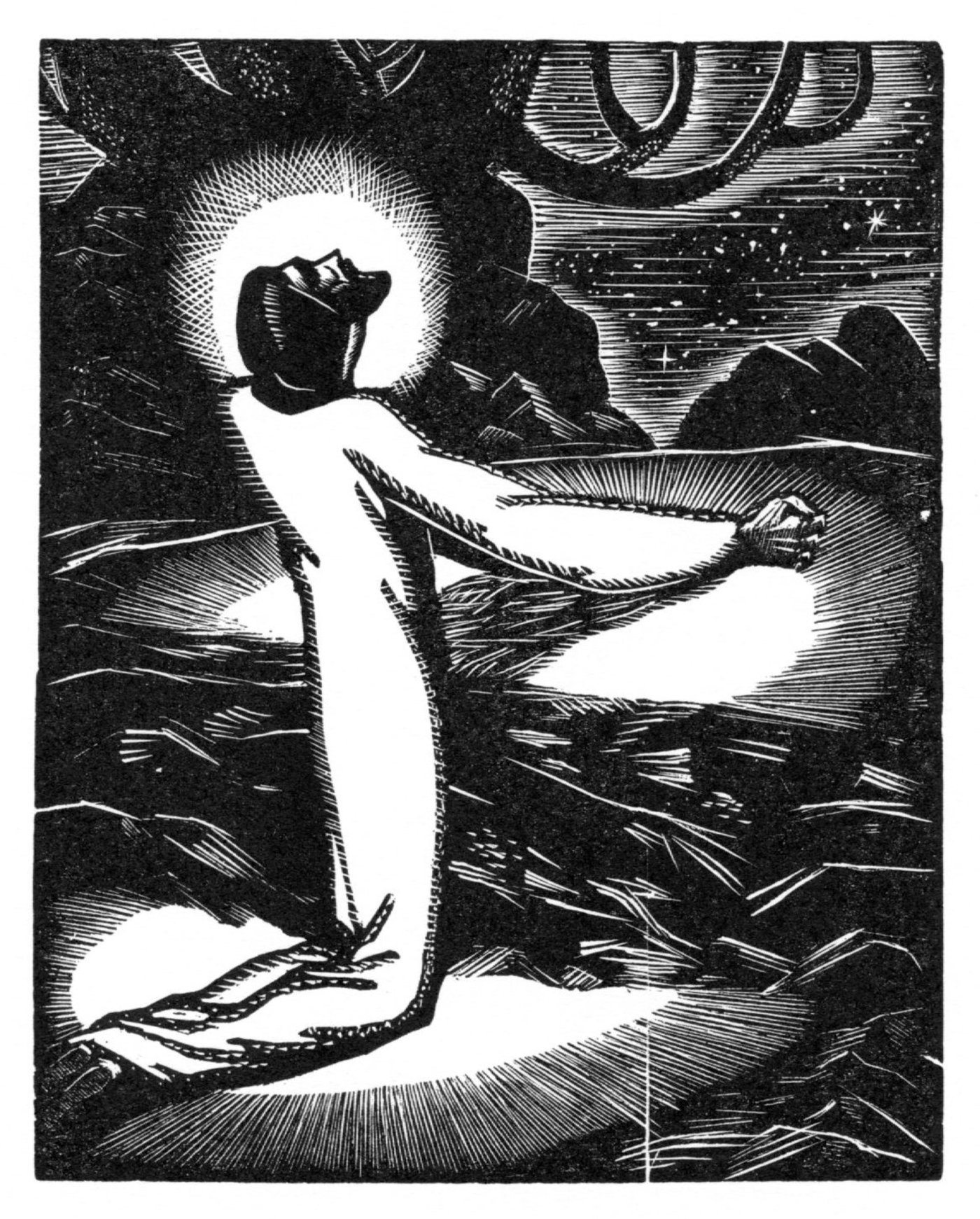

A few years ago a friend gave me a book called “The Life of Christ in Woodcuts” by James Reid — per the jacket one of “a host of maverick artists” from the early 20th century who “introduced the idea of the graphic novel, a story told exclusively with wood engravings.”

Originally brought out in 1930, the book was republished in 2009 by Dover Press.

“Glory be to God,” wrote poet Gerard Manley Hopkins for “All things counter, original, spare, strange.” I can hardly think of a better description of the person of Christ, nor of a more eloquent portrayal of that strangeness than that to be found in Reid’s work.

These beautiful, highly accomplished woodcuts make for a deeply moving book. Without using a single word, Reid somehow manages to convey the whole sweep of Christ’s birth, life, death, and resurrection. Interestingly, the cuts are not even titled: instead, the book is divided into four sections: “The Infant,” “The Boy,” “The Son of Man” and “The Messiah.”

A sorrow and a deep silence seem to surround Christ, starting in infancy and continuing throughout his exile on earth: the flight into Egypt, the garden of Gethsemane, the deposition before Pilate, the crowning with thorns.

One of my favorite blocks is of Christ as a young man, watching from afar as the other young people are pairing up, walking arm in arm around town.

Though only the back of his head is visible, you can see the idea forming: Oh, that looks lovely. That is one of the highest callings for a human being, marriage and children! … And somehow … I am meant to live out another mystery.

I posted a piece about the book on my blog back in 2011. Shortly afterward, I received an email from Robert Strossi of Brier Hill Gallery in Boston.

He wrote: “Last year, I published a limited edition portfolio of wood engravings from both ‘The Life of Christ in Woodcuts’ (Farrar & Rinehart, 1930) and ‘The Song of Songs’ (Farrar & Rinehart, 1931), printed directly from the surviving blocks in possession of the Reid family. You can see the engravings at my website.”

The Brier Hill Gallery site is a splendid place to lose yourself for an hour or two. From its “About” page: “Brier Hill Gallery offers fine prints, illustrated books, and limited-edition publications, specializing primarily in 20th- and 21st-century works.

While familiar names are well represented, we seek and promote the work of highly talented — if less well-known — men and women who merit the attention of fellow print enthusiasts. … Fine art need not be prohibitively expensive.”

Strossi then sent along the portfolio, a piece of art in itself, that he’d mentioned in his email. Printed on elegant stock (Mohawk Superfine by Puritan Press, Hollis, New Hampshire), the portfolio includes photos from the original book, a 1930 portrait of Reid by American painter Arthur Meltzer, and a beautifully written essay.

“How could an artist as talented as James Reid possibly have been forgotten?” Strossi asks, then offers a brief biography, reports on the technical details of the original printing, and tells the story of searching for and finding the remaining members of the Reid family — who just happened to have a cache of their father’s original woodblocks.

Reid (1907-1989) was born and educated in the Philadelphia area. He married Alyse Worthington, a dancer and dance instructor, in 1925. The couple stayed together for almost 64 years — Alyse was his staunchest champion — and had three children: Alyse Reid Smith, Gale Reid, and Nancy Reid Woron.

Reid signed a book contract for “The Life of Christ in Woodcuts” on April 11, 1930, with Farrar & Rinehart, and for “The Song of Songs” the next year.

Though “The Life of Christ” was well received, the Depression was in full swing and the work of a fellow woodcut artist released at about the same time, Lynd Ward’s “God’s Man,” overshadowed Reid’s achievement.

Reid later described lugging his canvases around New York City by bus during that time in an effort to make a sale: “Those Depression days were noted for threadbare soles, my shoes no exception, and following the accepted practice I would trim a piece of cardboard to fashion innersoles.”

He never earned back his $500 advance on the book. In order to support his young family, he went on to a successful career in commercial art.

I tell the story at some length because it’s a story about people who have cultivated the eyes to see and the ears to hear what is beautiful, good, and true. People who had, and continue to have, faith that the seed planted in love will grow in darkness and bear fruit, somehow, sometime, in some person or way that we very well may not be given to know.

“Fine art need not be prohibitively expensive.”

“To the end of [her] life, [Reid’s wife Alyse] believed that his talent would one day receive the recognition it deserved.”

From the Reid heirs, in giving gracious permission to use these images: “We feel the more people that get to see Dad’s work, the better for everyone.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books. For more, visit heather-king.com.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!