On Jan. 22, the Vatican-supported Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons entered into force, officially becoming international law.

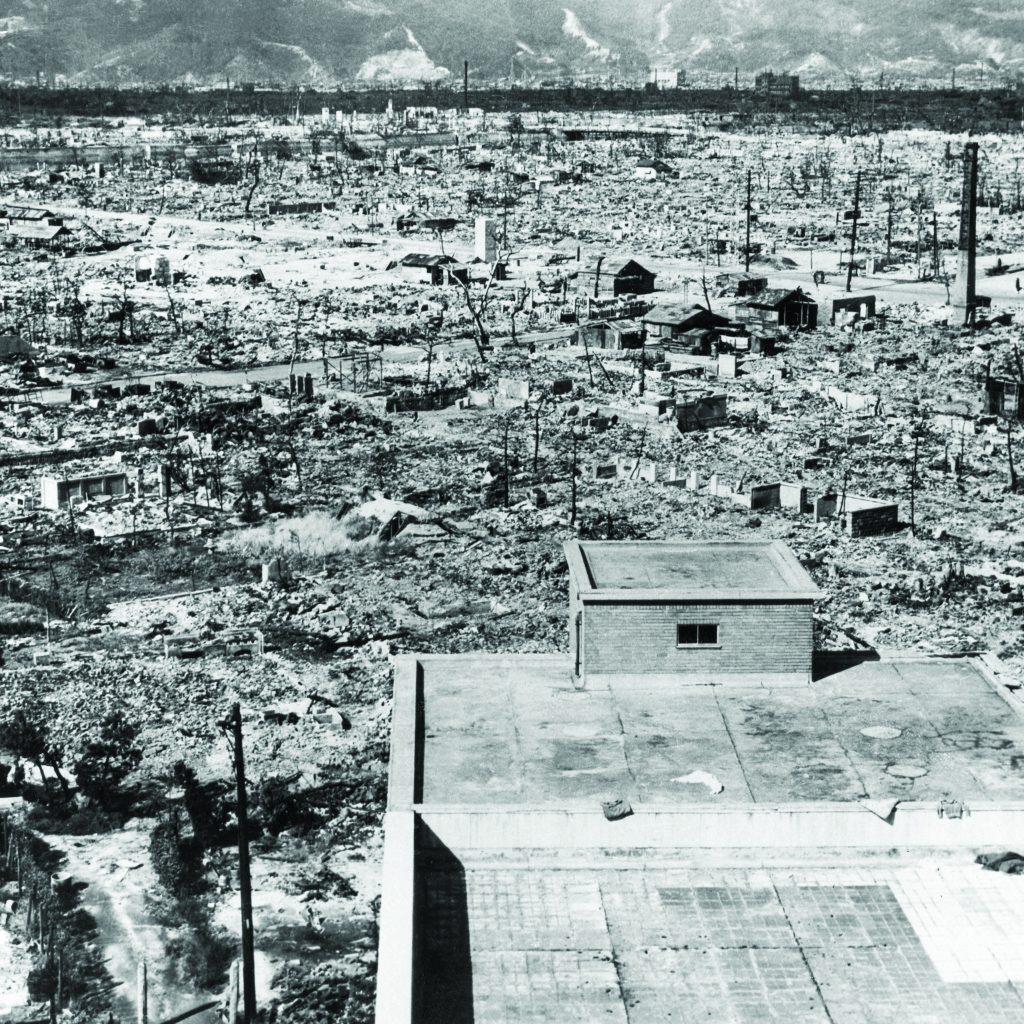

Fake news or suppressed news or no news hardly began in the 21st century. After the 1945 decimation by atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, for example, the U.S. government and military immediately began a campaign to hide the horror of the devastation and the particulars of the human toll. The suppression worked — for a time.

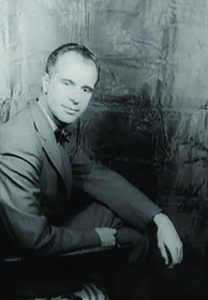

“Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World,” by LA-based journalist Lesley M.M. Blume (Simon & Schuster, $27), recounts the tale of how New Yorker journalist John Hersey found his way into Hiroshima, settled upon six individual victims of the bombings, and told their stories.

Hersey was a seasoned, globe-trotting journalist, no stranger to savagery and butchery. “The best chance that mankind had for survival — especially now that warfare had gone nuclear, [he] felt — was if people could be made to see the humanity in each other again.”

But when he arrived in Japan, over a year after the dropping of the bombs, he was staggered by what he found. A mother who’d clung to her dead infant daughter until the body started to decompose. Human beings who had been vaporized, leaving only shadows on the ground or walls. Residents, desperate to rebuild, who were still coming across severed limbs and charred corpses.

Hersey interviewed dozens of survivors and chose six upon whom to focus: a German Catholic priest, a Methodist pastor, two Japanese doctors, a young female clerk, and a widowed seamstress, mother to three young children.

The New Yorker, in an extraordinary editorial decision, decided to dedicate its entire Aug. 31, 1946, issue to a single article: Hersey’s 30,000-word piece, entitled simply “Hiroshima.” Published two months later as a book, the title has sold more than 3 million copies and has never been out of print.

With today’s combined inventory of nuclear arms comprising more than 13,500 warheads, Blume notes, “The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a nuclear watchdog group, has reset its Doomsday Clock — which gauges the world’s proximity to the possibility of nuclear war — to ‘100 seconds before midnight,’ with midnight meaning nuclear apocalypse. The clock has never been this close to midnight — not even in 1953, ‘the most dangerous year of the Cold War,’ says Dr. William J. Perry, former U.S. secretary of defense and chair of the Bulletin’s board of sponsors. … And nothing is being done to reduce the dangers.”

That last is not entirely accurate. The Kings Bay Plowshares 7 action on April 4, 2018, in Georgia, for example, is just one of more than 100 Plowshares actions, undertaken in concert with the effort to abolish nuclear weapons with people around the world.

Father Steve Kelly, SJ, one of the seven, served almost three years and is now being (very slowly) transported to Tacoma, Washington, to face charges for violating probation with respect to another action there. All told, he has spent 10 years in prison in an effort to avert the possibility of omnicide — the literal wiping out of human life — for which the capability exists.

“Nuclear weapons will not go away by themselves,” he quietly observes. “It is my lifelong quest to imitate the Good Shepherd. I will insert myself between the dangers and the flock.”

I’m haunted by a conversation I had with a politically disgruntled friend last year. “Love doesn’t prevail,” he said. “Love doesn’t triumph. Look at the racism. Look at our ‘elected officials.’ ”

“Love rarely prevails in a way that brings about a worldly triumph,” I replied. “But love is about the conversion of the human heart, not winning. And in some way we’re not given to see on this earth, I believe love always prevails.” To illustrate, I mentioned the small but fervent movement against nuclear weapons. I gave Father Kelly as an example.

“That won’t do any good!” my friend scoffed. “We need to start blowing things up and burning stuff down. The really brave, original, radical people are realizing that we need to start exercising the freedom to hate.”

I’m not sure what was more horrifying: that an otherwise intelligent human being would believe “the freedom to hate” to be an original idea, or that his heart was not moved by the silent, solitary witness of this man who has spent years of his life crying out in the wilderness. A witness who has virtually no “public profile,” no online presence, who has never asked to be recognized, validated, or applauded.

That not a single atomic weapon has been dropped on a human population since 1945 is a fact that many attribute to Hersey’s exposé.

John Hersey, one journalist.

Father Kelly, one man, accompanied and supported by the unsung fleet of others who have put their lives and freedom on the line through the years to rid the world of these weapons of hate.

Both have been accompanied, of course, by innumerable others, in and out of the Church, whose names we will never know: international peace organizers, U.N. committee persons, men and women of prayer.

And now a treaty with respect to which the Vicar of Christ himself has proclaimed that nuclear weapons are a sin.

I wonder how that happened.