In these dog days of summer, who doesn’t want to sit in a darkened, air-conditioned theater for an hour? I sure do. Thus I recently found myself at the IMAX down near USC watching “The Human Body.” (Show times are at 10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 p.m. and 5 p.m. through Sept. 4.)

For those of us drawn to the psalmist’s “You knit me together in my mother’s womb” and who center our lives on the Eucharist, little could compel more than the human body.

(I was also poised to visit “Body Worlds: Pulse” at the adjacent California Science Center, but learned that sponsor/impresario Gunther von Hagen has generated controversy in the Church for his lack of respect for the bodies of the deceased. So I skipped that one.)

Nothing too strenuous: the film’s target audience seems to be 8 to 10-year-old boys. The opening shot is of what looks to be a skin-covered volcano with a hairy opening.

Our bodies are 65 percent water and 22 percent carbon. They contain traces of gold, arsenic and rust. They’re 100 percent unique. If we’re lucky, each of us might live to see a new day begin more than 27,000 times.

We’re introduced to a day in the lives of Heather, a pregnant 30-year-old with excellent teeth and skin; Buster, her husband; Luke, Heather’s nephew; and Zannah, Heather’s niece (Heather and Buster are housesitting.)

The family wakes up and bumbles around in their pajamas. Then Buster cuts himself shaving and all hell breaks loose. We’re plunged into the magnified-50,000-times human circulatory system. We lose 200 billion tiny red blood cells a day. Then again, we make 2 million every second.

We move on to the brain, which presides over everything from breathing to office politics, and is the most complicated mechanism in the universe.

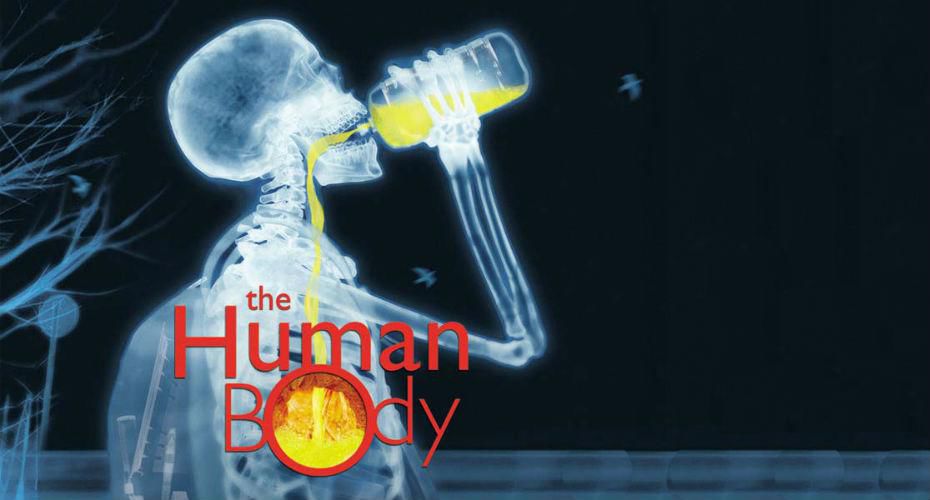

Teenager Luke rides his bike to school, a feat requiring 300 coordinated muscles that move almost every bone in the body. Everything that’s alive gives off heat. Infra-red imaging illustrates. Luke and his dog, trotting along behind, are reduced to moving skeletons so we can see how it all works.

Next we see a clambering baby skeleton with two cute little top teeth. Turns out we crawl over 60 miles our first two years on earth. Our first six months, we also retain what is called the diving reflex. A baby placed underwater will instinctively know not to breathe and will also instinctively move its torso and limbs in such a way as to propel itself through the water. Some think this is a holdover from when the earth was covered with water, a reflection of our ancient kinship with sea creatures.

Heather has lunch with a friend. We see halved cherry tomatoes and fusilli pasta coursing down the esophagus and then into the stomach, where our food is churned as if in a washing machine. The walls of the intestine look like a super-plush polar fleece blanket.

The walls of the fallopian tubes resemble an ash-covered lunar landscape. Look! Nestled among the crags and folds is an egg — the largest cell in the human body, just visible to the naked eye! The sperm, by contrast, is one of the smallest. As Marvin Gaye croons “Let’s Get It On,” a colony of back-lit neon sperm jiggle, jounce and jive. Hey, where’s my egg, man!

We see individual red blood cells the size of the whole IMAX screen. We travel through the circulatory system to the beating heart, which looks like the back room of a butcher shop and sounds like Niagara Falls.

In a segment on puberty we’re treated to close-up of teens popping zits and their thoughts on the unsightly hair that has begun to sprout all over their poor, transmogrifying bodies. A wilderness. A forest. Gross!

Eight-year-old Zannah tries on various outfits that will appall her in a few years, clamps on headphones, dances dreamily in front of the mirror in her bedroom.

This leads us inside the eardrum, with its chains of tiny bones. We travel through the cochlea, lined with hairs so miniscule that 100,000 bunched together would still be thinner than a single hair on our heads.

But the single most mysterious change of which the human body is capable occurs during a woman’s nine months of pregnancy. Heather, many months along, reclines on her sister’s sofa and reflects on the wonder of a body that knows what to do without our telling it.

At the end, tastefully swathed in white blankets, she has her baby. You cry.

On the way back to my car, I wandered the Exposition Park Rose Garden. No X-ray could have detected the emotions evoked by the beds of just past-peak blooms labeled “Pretty Lady,” “Strike It Rich” and “Antigua.” No imaging machine could have explained why I sank to the ground beneath a tree for a few minutes, drinking in the honeyed light of early August

As Henry James said, “Summer afternoon — summer afternoon; to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language.”