If gunpowder had been available in the first century, we would probably be using fireworks today for the Easter Vigil. Ditto lasers.

On the night before the great feast day, the early Christians kept a vigil that made a lasting impression — on believers and on history. The symbols were elemental: fire, water, darkness, nakedness, music, dramatic preaching, surprising chalices, and more-than-marathon endurance.

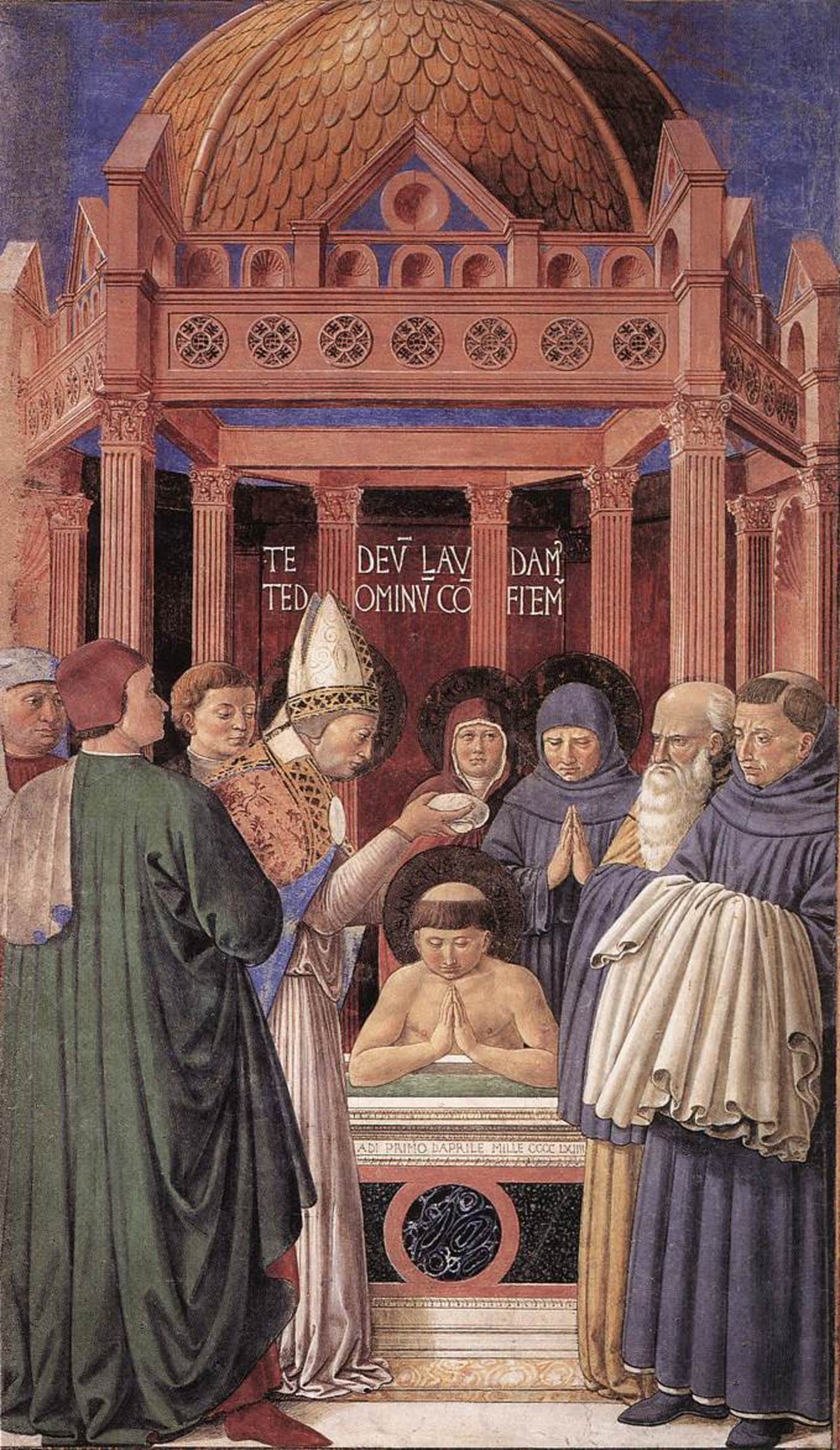

It was the great night when Jesus rose up from death and the tomb. It was the great night when new Christians were baptized and received Holy Communion — both sacraments that had been kept secret till that moment. There was drama. There was surprise. There was every reason to stay awake all night.

Lasted all night

The custom of keeping watch before Easter is ancient. An Egyptian document known as the “Letter of the Apostles” (“Epistula Apostolorum”), produced around A.D. 160, traces the origin of the vigil to a command from Jesus himself. “When Easter is coming,” he tells his disciples, they should “keep the night watch … until cockcrow.”

A document of the following century, the “Didascalia Apostolorum,” claims by its very title to bear the “Teaching of the Apostles.”

This prescription, set down in the Syriac language, goes on in greater detail: “You shall come together and watch and keep vigil all the night with prayers and intercessions, and with reading of the Prophets, and with the Gospel and with Psalms, with fear and trembling and with earnest supplication.”

So we know that the vigil was not simply a time of waiting. It was a liturgy — a ritual act of worship — a time when the Church read large portions of the Bible, sang psalms, and offered prayers. And, again, it lasted “all the night” long.

The greatest Scripture scholar of the ancient Church, Saint Jerome, insisted that “we have the tradition from the apostles that the congregation is not to be dismissed before Midnight during the Easter Vigil.”

He explained that the Jews believed the Messiah would arrive at night, during the hour when the first Passover had been celebrated in Egypt. He noted, furthermore, that Jesus, in the Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, spoke of the Bridegroom arriving “at midnight” (Matthew 25:6). So it was reasonable, he concluded, to require Christians to stay till twelve.

But the rite itself could — and usually did — go on much longer, indeed “until cockcrow,” which is just before daylight. Testimonies from the middle and late 100s — in lands from North Africa to modern Turkey — reveal that the clergy did not even begin to celebrate the sacraments (baptism and Eucharist) until dawn.

Darkness to bright light

Saint Augustine lived a long life and preached at many Easter Vigils. It was emotional for him, because it revived the memory of his own reception into full communion at age 33. He called it “the mother of all vigils.”

(WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

The long liturgy signified every Christian’s lifelong journey, he said, “from darkness to light.” During the night, Christians were to focus on the Scripture readings as if they were the only rays of light.

Light was introduced, suddenly or gradually, depending on the local customs. In Europe in the fourth and fifth centuries, it became fashionable to use Easter candles made of wax.

Saint Jerome abhorred this as an unacceptable and unbiblical novelty, since the biblical figures used oil lamps and not candles. But the fashion caught on, and even Saint Augustine wrote a hymn to the Easter candle.

When Christianity was legalized, the light was extended beyond the Church to the entire city. The fourth-century historian Eusebius said that the Christian Emperor Constantine “changed … the holy night vigil into a brightness like that of day, by causing waxen tapers of great length to be lighted throughout the city.”

An exciting story

From the ancient lectionaries we learn that the program included as many as 12 Bible readings, some of them quite long, with psalms sung in between. The night itself was to be the overarching story of God’s relationship with the human race — from creation to fall to redemption.

Its highlights were dramatic: Noah’s rescue from the raging flood; Abraham’s vocation to sacrifice his only son Isaac; Israel’s deliverance from slavery in Egypt; the Chosen People’s restoration from exile in Babylon.

It was a single epic woven from many great adventures. It was communal — the story of all. But it was personal, too — the story of each.

Today’s congregations squirm at the thought of so many long readings. But matters were different in an age before electronic media — and before the printing press.

Books were expensive, and relatively few people could read. So people relished the chance to hear a good story well told. And there was none greater than the whole-Bible story of the Easter Vigil. This was entertainment.

The presiding bishop or priest connected the readings in a stirring homily. The earliest surviving example is from the mid-100s, by Saint Melito, the Bishop of Sardis.

It is a long and stunning work of vivid, rhythmic poetry, and it must have thrilled the assembly of first-time hearers. Melito explained why Jesus’ death and resurrection were foreshadowed in the events of Israel’s history.

What is this strange mystery,

that Egypt is struck down for destruction

and Israel is guarded for salvation?

Listen to the meaning of the mystery.

This is what occurs in the case of a first draft;

it is not a finished work but exists so that, through the model,

that which is to be can be seen.

Therefore a preliminary sketch is made of what is to be,

from wax or from clay or from wood,

so that what will come about,

taller in height,

and greater in strength,

and more attractive in shape,

and wealthier in workmanship,

can be seen through the small and provisional sketch.

What the congregation witnessed at the vigil was the completion of God’s great work of art, in their own sight and in their lives.

New Christians

It was at the vigil each year that the Church welcomed converts. Through the first three centuries, most converts were adults who had been raised to worship the gods of the Roman, Greek, and Egyptian cults.

The practice of Christianity was illegal until A.D. 312 and was punishable by death. Many believers perished as martyrs, and others suffered discrimination if they were known to be Christian.

The deterrents to faith were great, and the Church made clear the possible consequences to anyone who asked for baptism. Some candidates underwent years of preparation before their reception at the Easter Vigil.

All of them — in fact, everyone attending the vigil — prepared for the day by fasting. The “Didascalia” restricted the diet of the faithful to bread, water, and salt for Monday through Thursday of Holy Week. And, as if that weren’t rigorous enough, it called for no food whatsoever on Friday and Saturday.

Christians also prepared by bathing, usually on Holy Thursday. Through those centuries there was no running water or household plumbing. A bath was considered a luxury. But Christians would indulge in it during Holy Week, to ready themselves for the great feast.

Candidates for baptism were especially encouraged to wash, so that they wouldn’t muddy the sacramental pool when they were immersed.

Spitting at Satan

The ancient rites of baptism were elaborate, involving a procession from outside the church to various stations within the church. The movement, of course, symbolized the individual’s journey toward God.

Since Christians always worshipped facing east, the candidates would begin by facing west. In that direction, opposite God, was the devil; and the former pagans would explicitly reject him “to his face.”

The rite differed from region to region. In some churches the converts spat in the devil’s direction. In others they exhaled in order to drive him away. And then they processed inside for baptism.

Baptized naked

It is Christian doctrine that baptism signifies birth to a new life. So converts underwent this second birth just as they had undergone their first: completely naked.

It wasn’t as scandalous as it sounds. The churches were segregated by sex, and modesty was scrupulously respected. Female candidates were obscured by a screen that blocked the view of everyone, including the bishop who baptized them.

He first poured water over the top of the screen. Then, at the anointing, he poured oil over the top onto the woman’s head. The bodily anointing, for women, was completed by holy women, called “deaconesses,” who were commissioned for the task.

In the fourth century Saint Cyril of Jerusalem recalled the moment for his class of newly baptized Christians.

“As soon, then, as you entered, you put off your tunic,” he said, “and this was an image of putting off the old man with his deeds (Colossians 3:9). Having stripped yourselves, you were naked, in this also imitating Christ, who was stripped naked on the cross, and by his nakedness put off from himself the principalities and powers, and openly triumphed over them on the tree.”

Coming up out of the baptismal pool, the newborn Christian received a white garment to wear. Saint Cyril said this change of clothing symbolized a putting off of the “old man” to be replaced by the new.

“May the soul which has once put him off, never again put him on … O wondrous thing! You were naked in the sight of all, and were not ashamed; for truly you bore the likeness of the first-formed Adam, who was naked in the garden, and was not ashamed.”

A surprising chalice

The sacraments were, in those days, celebrated in strict enclosure. Only fully initiated believers were permitted to attend Mass or baptism, and they were forbidden to discuss the ceremonies with nonbelievers. Historians call this the “discipline of the secret.”

Surely some of the rites arrived as a surprise to the converts. Another thing presented to them after immersion was a chalice, from which they were to drink. By taste they would recognize its contents: milk and honey. And they would recognize its significance.

Through the baptismal waters they had crossed into the promised land, which God had foretold as “a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:8). They had reached their true home.

Singing a new song

In full daylight, then, the Church celebrated the Eucharist. After fasting for days and keeping vigil for a full night, the Christians at last knew communion with God, and they sang the distinctive song of Easter, which had been held back during Lent.

Alleluia!

Mike Aquilina is a contributing editor to Angelus and the author of many books, including “The Fathers of the Church” (Our Sunday Visitor, $24).

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!