ROME — Jan. 1, 2020, marks not only the beginning of a new year, but, in this case, a whole new decade. The 2010s will be officially over, and to call them “momentous” for the Catholic Church would be a gold-medal winner in understatement.

Ticking off the biggest Catholic stories of the past decade is fairly easy, at least in terms of the first two spots: No. 1 is clearly the Feb. 11, 2013, resignation announcement of Pope Benedict XVI, followed closely by the March 13, 2013, election of Pope Francis. Those two events have changed the Church in fundamental ways, not only in the here-and-now but permanently.

The problem with such papal thunderclaps, however, is that they tend to obscure other important turning points and trajectories over the past decade, which are every bit as much a part of the Catholic story.

Herewith, then, is a highly subjective countdown of the most neglected Catholic stories of the 2010s, ones, notably, that don’t (at least directly) pivot on popes.

No. 5: Dino Boffo

What Italians call the “giallo,” literally meaning “yellow” but used to refer to a mystery surrounding Italian Catholic journalist Dino Boffo, first erupted in 2009. Facing accusations that he had harassed a woman because he wanted to pursue a gay affair with her lover, Boffo resigned as editor of L’Avvenire, the newspaper of the Italian bishops, in September 2009.

In mid-January 2010, the case reignited after revelations that a purported police document about Boffo was a fake. Speculation ensued in the Italian press about who was behind it, which congealed into the following hypothesis: The Vatican’s then-Secretary of State, Italian Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, wanted to get rid of Boffo because he was associated with the late Cardinal Camillo Ruini, the former president of the Italian bishops and a rival for preeminence in Italy.

Cardinal Bertone supposedly enlisted the editor of the Vatican newspaper and the head of the Vatican gendarmes in the plot.

In reality, that reconstruction never passed the smell test. To begin with, a secretary of state has far less complicated ways of sacking the editor of L’Avvenire, but it captivated the country for a full 18 days before the Vatican made any comment.

When a Vatican spokesperson was finally authorized to reject the accusations, one Italian paper carried the following banner headline, which seemed to capture the moment: “The Vatican Denies Everything, No One Believes It.”

The case was paradigmatic for all the Vatican scandals of the decade to come: character assassination, the weaponization of political differences, and the inability (or unwillingness) of Vatican communicators to respond effectively.

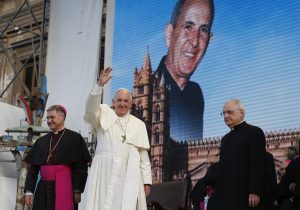

No. 4: ‘Pino’ Puglisi and anti-Christian persecution

The May 25, 2013, beatification of Puglisi, an anti-mafia priest from Palermo in Sicily gunned down in 1993, was arguably the most important papal act with regard to Catholic sainthood of the early 21st century.

To begin with, Puglisi is an ideal patron saint for today’s new generation of Christian martyrs. The number of Christians killed for reasons linked to their faith is approximately 100,000 every year, with millions more facing other forms of violent persecution.

The broader significance is this: Historically, the Church has recognized martyrs only if they were killed “in odium fidei,” meaning “hatred of the faith.” Puglisi, however, was recognized as a martyr who died “in odium virtutis et veritatis,” meaning “hatred of virtue and truth.”

That category has always existed in classical Christian theology, but the Puglisi beatification means it’s now being applied to sainthood causes and could accommodate countless similar situations of contemporary martyrdom.

No. 3: Church as change agent in Africa

When civil war broke out in the Central African Republic in 2012, the local Catholic community sprang into action, led by then-Archbishop, today Cardinal, Dieudonné Nzapalainga of Bangui. He became one of the “three saints of Bangui,” together with Rev. Nicolas Guerekoyame-Gbangou, president of the country’s Evangelical Alliance, and Imam Oumar Kobine Layama, president of the Islamic Council.

As violence along Christian-Muslim lines gripped the nation, the three men organized prayer sessions, rotating the encounters to include the Catholic cathedral, the great mosque in Bangui, and Protestant churches.

They also promoted “peace schools,” where children of all different religions can study, as well as mixed health care centers open to everyone. In 2014, Time magazine named them among the 100 Most Influential People in the World and the United Nations awarded them the 2015 Sergio Vieira de Mello Prize for Peace.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018, the bishops’ conference was the mediating body that helped push President Joseph Kabila not to seek a third term in office. In Zimbabwe in 2017, a Catholic priest also played a key role in getting long-serving nonagenarian President Robert Mugabe to accept it was time to step aside.

All across sub-Saharan Africa, and not only in predominantly Catholic countries, Church leaders are often seen as the first mediators in civil conflicts, and the most important voices in speaking out against human rights abuses, fair elections, and the rule of law.

In part, that’s because of the massive growth of Catholicism in Africa; also, it’s because Africans tend to trust spiritual leaders much more than politicians, journalists, lawyers, and social activists.

In many ways, global Catholicism is entering an “African moment,” and it’s one that promises an engaged, activist Church.

No. 2: The ‘Catholic Dunkirk’ on the Nineveh Plains

When it comes to the bleak landscape of contemporary anti-Christian persecution, hope often can seem to be in short supply. Yet right in the eye of the storm when it comes to anti-Christian violence is one of the most hopeful Christian narratives of the early 21st century.

The devastation of Christianity in Iraq following the U.S.-led invasion of 2003 is well-documented. In 2003, there were an estimated 1.5 million Christians, while today the high-end number for those left is usually set at around 300,000. Similarly, Syria’s Christian community is believed to have been cut in half.

The bulk of public humanitarian aid in Iraq and Syria is delivered through major refugee camps. However, Christians typically don’t go to those camps, fearing infiltration by Jihadist loyalists and thus further exposure to persecution and violence. As a result, from the beginning, the Christians have been basically abandoned by most international relief efforts.

To fill the void, private Christian organizations around the world, the lion’s share Catholic, have stepped up over the past decade, ensuring those Christians are fed, sheltered, and have access to medical care; and, more importantly, that they have the promise of a better future to come, thereby offering them a reason to ride out the storm.

The leading example is the Nineveh Plains Reconstruction Project, aimed at revising the historical cradle of Christianity in northern Iraq that was laid waste during the ISIS occupation.

Fueled largely by private donors such as Aid to the Church in Need, the Knights of Columbus, and the Catholic Near East Welfare Association, approximately 45% of the population has returned. Shops have reopened, many houses have been repaired, and Church life has resumed, including catechism, radio, schools, and women’s groups.

Someday, this “Catholic Dunkirk,” only a Dunkirk in reverse, a civilian flotilla to help people stay rather than escape, may be commemorated in celluloid, becoming a story passed down from one generation to the next. For now, perhaps it’s enough that the efforts not pass in silence.

No. 1: The ‘great reform’ on clerical sexual abuse

With regard to the clerical sexual abuse scandals, the 2010s were a tale of two decades for the Catholic Church.

On the one hand, the decade opened with the aftershock of the Irish abuse crisis and the subsequent eruption of similar scandals in Germany, Belgium, and other parts of Europe.

It’s closing with arguably the world’s most intense abuse crisis to date in Chile, as well as the aftermath of the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report and the scandal surrounding ex-cardinal, and ex-priest, Theodore McCarrick in the United States.

We’re also awaiting the final word from Australia’s Supreme Court on Cardinal George Pell’s appeal of his conviction for “historical sexual offenses.”

In other words, it was a decade of heartache, shock, anger, and disappointment. All of that has been extensively chronicled, and it remains the object of extensive litigation, protest, and debate.

On the other hand, the decade also witnessed what could be termed a “great reform” on abuse, a historic course correction, remarkably swift by the typically evolutionary standards of Catholicism, from denial to reform, from defensiveness to contrition, and from passivity to action.

Strong accountability measures for the crime of child abuse have been adopted, stronger in some places than others, to be sure, with the U.S. and the West generally leading the way, and the rest of the Catholic world, to varying degrees, catching up.

Rome’s Jesuit-sponsored Gregorian University and Father Hans Zollner, SJ, a close papal adviser, have emerged as a global nerve center in anti-abuse efforts, not just in the Church but across the board. Reformers such as Maltese Archbishop Charles Scicluna have been empowered, while those in denial have been driven underground.

Pope Francis has repeatedly amended Church law to facilitate the fight against abuse, most recently by lifting the requirement of pontifical secrecy to encourage cooperation with civil prosecutions in abuse cases. Survivors of abuse, once given the bum’s rush by the Church when they tried to get a hearing, are today among the pope’s counselors.

A new generation of bishops has arisen over the last decade, whose priesthoods have been scarred by the abuse crisis and who feel determined to face it head-on. They include Auxiliary Bishop Mark Dowd of Montreal, Canada, who in 2018 and 2019 helped convict a pedophile priest by launching his own investigation and turning his findings over to police, encouraging victims to come forward.

None of this has played to the same fanfare, in part because it contradicts the narrative of a Church still in denial.

God knows there are still huge gaps in the Church’s response and significant unfinished business, beginning with enforcing the same accountability for the cover-up of child abuse it presently imposes for the crime itself. Measures for that kind of accountability now exist on paper, but they haven’t been demonstrated in practice.

Yet to pretend that nothing at all has happened over the past 10 years, that the Catholic Church will be in the very same place on the abuse scandals in 2020 as it was in 2010, would be a massive act of denial.

The truth is, the decade brought good news and bad, both hope and anguish. The only difference is that, perhaps predictably, the anguish seemed to get most of the attention.