In the uproar over the leak of an early draft of a Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision legalizing abortion, the rhetoric of editorialists and commentators friendly to abortion has been short on light but long on heat. Even the conclusion of The New York Times editorial — “If you thought Roe v. Wade itself led to discord and division, just wait until it’s gone” — left you wondering: Is that a prediction or a threat?

At this time of unbridled passions, it makes sense to recall T.S. Eliot’s wise saying, “The end is where you start from,” and reflect on what the founders of the abortion movement really saw as ultimate ends. And on that question no source speaks with more authority than Lawrence Lader.

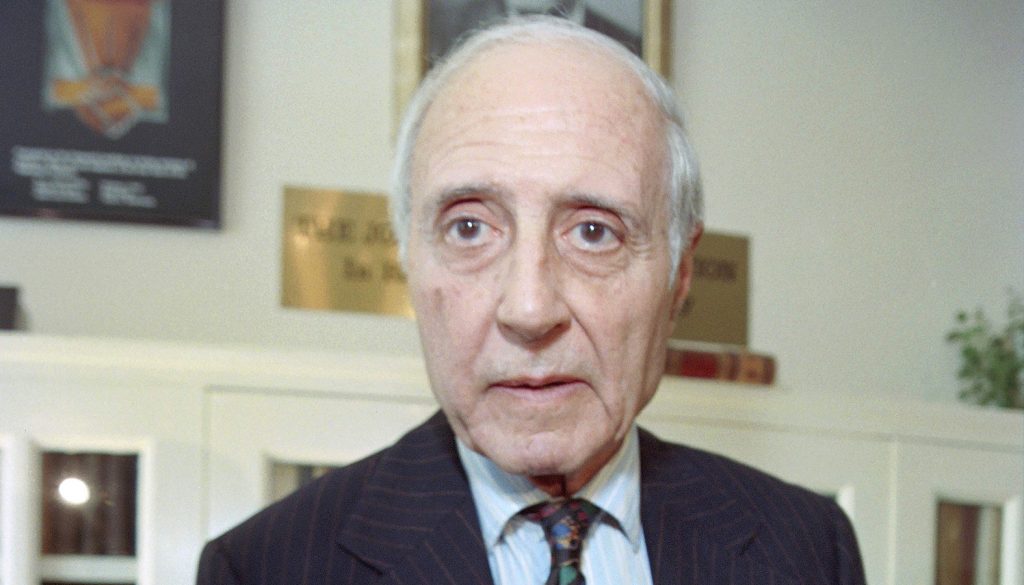

Probably few people today remember Lader, but feminist writer Betty Friedan admiringly declared him “the father of the abortion movement.” Among other things, he wrote the most influential abortion advocacy book before Roe, and his handiwork was cited nine times by the majority opinion in that case. He remained a stalwart of the pro-abortion crusade up to his death in 2006 at the age of 86.

Lader was a journalist who wrote for magazines in the years after World War II. His 11 books included a biography of Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood, and a volume arguing the case for the abortion drug RU-486. As a leader in the abortion movement, he was a co-founder of a group called the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws — now, NARAL Pro-Choice America.

Among the targets of Lader’s zealotry was the Catholic Church. In his book “Politics, Power, and the Church,” he argued that on divorce, school prayer, abortion, and other issues the Church “sought to legalize its moral codes.” In 1988-89 he brought suit against the Internal Revenue Service demanding an end to the Church’s tax-exempt status, but that effort went nowhere.

The high point of his abortion advocacy unquestionably was “Abortion.” Published by Bobbs-Merrill, the book came out in 1966 shortly after the Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold v. Connecticut overturned an antique Connecticut anti-contraception statute. Griswold was notable for asserting a constitutionally protected right to privacy, something Lader correctly recognized as the pathway to legalized abortion. A followup volume, “Abortion II,” was even more upfront in acknowledging its author’s radical goals.

So what exactly did Lader have in mind? Let him speak for himself.

Abortion, he declared, was “the final freedom” for women. But freedom for what? Abortion would be “the prime weapon against sexism and the ‘biological imperative’ — the prison of unwanted childbearing.” But that wasn’t all. “Once sex had been detached from pregnancy, Women’s Liberation could construct its own ethics on the ash-heap of puritan morality.” And ultimately the “most radical feminist” (and, it would seem, Lawrence Lader himself) “wants an even more sweeping revolt — the end of the nuclear family.”

Worth noting is the tinge of eugenics in Lader’s writing. Usually it’s cloaked in high-sounding language (“every child a wanted child”), but here and there it breaks through, as in this: “Above all, society must grasp the grim relationship between unwanted children and the violent rebellion of minority groups.”

Abortion, eugenics, destroying the nuclear family, stamping out sexual morality, silencing the Catholic Church. These were among the ends pursued by the father of the abortion movement in a long, notably successful, and highly destructive career. If the movement Lawrence Lader launched has disavowed them, I’m sorry to say I missed it.