As a new member of the semi-retired community, I have developed a schedule for myself, until the time when another paying entity schedules one for me.

I am an early riser. I know, I have seen the commercial, the fact I get up exceptionally early is not a matter of interest to anyone else but me. Still, I write best (or as best I can) early in the morning.

Another advantage of semi-retirement, and early mornings, is that I can indulge my weakness for watching movies with little guilt. When I start a movie at 4:30 a.m., by the time the end credits roll, I am at my desk staring down blank pieces of paper or scribbling changes on the previous day’s efforts.

I have recently settled on crime and heist movies as part of my new early morning regime. I pick them randomly. Sometimes I cannot make it through the opening credits. Sometimes I watch an entire movie and wonder why I wasted the precious pre-dawn hours. And sometimes I see well-made movies that hold my attention.

But what I almost always see are movies not very keen on presenting the moral universe I was instructed in at St. Elizabeth’s parish grammar school. Great films and great art in general do not require overtly religious themes, and are not void of sin.

If this is a spoiler alert, you ought to be ashamed of yourself, but the plot of Hamlet is initiated by an adulterous affair that turns murderous, and by the end of the play just about all the principles are dead, the violent result of failing to adhere to a set of objective truths. In today’s popular entertainment, antagonists and protagonists alike play by rules of their own formation.

Adam and Eve tried this in the Garden of Eden. The serpent encouraged Eve, and Eve passed it along to Adam that the rule God imposed — just one rule, mind you — should be discarded if they wanted to get the most out of life.

Apparently, living in peace, harmony, and without want or care in paradise was not enough.

Thousands of years of human history since then confirms this, as all powerful kings and dictators always want more, and the casualty list of people with vast riches but empty lives ending prematurely gets longer every day.

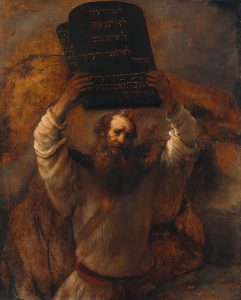

But there are rules: 10 of them.

Jesus gave us the Ten Commandments for “Dummies,” encapsulating all 10 within the confines of just two simple instructions. But as economical as Jesus was, he did not suggest the Ten Commandments were somehow rendered obsolete. Far from it, as all 10 fit rather perfectly within the context of Jesus’ top two commandments.

You would not recognize much adherence to two, let alone 10 commandments, in present-day crime genre movies. It seems to matter not whether the characters are robbing a bank, settling a gangland score, or bringing down a crime boss, there is no external, objective standard that either modulates an action or dispenses a consequence.

There are consequences, of course — the body counts in these movies are incalculable. In some movies I have seen, “wages” are paid for sins committed. But revenge is the primary virtue, and we are further manipulated to view the people perpetrating the crimes in a positive light by a never-ending stream of corrupt corporate types who seem to deserve to have their stuff stolen from them.

And the notion of the “good” bad guy, the character who exists outside the laws of God and man, but in the end initiates a selfless sacrificial act, has been rendered nostalgic.

The mistake is to consider this trend as a rejection of unmovable laws. It is about the replacement of one set of immovable laws written in stone from Mt. Sinai for another. If you think the intractability of the new code is overstated, look up “cancel culture.”

The question remains: Just who is in charge? Whether we are watching this new moral code play out on a television screen or within the reality of our daily lives, it would serve us all to remember that if we ever find ourselves in a room where we, or anyone else, is the arbiter of moral exactitude, we are in the wrong room.